Escape from Kupiansk: How one cop tricked the Russians

Editor’s note: Due to security concerns, the Kyiv Independent isn’t publishing the real name or the photo of the police officer at the center of this story. He is identified in the story as Oleksandr.

KUPIANSK, Kharkiv Oblast – Kupiansk police officer Oleksandr doesn’t like remembering the time he was abducted and tortured by invading Russian forces trying to recruit him.

In fact, it takes several of his colleagues to essentially bully him into it, unprompted.

“Has this man told you that he’s a hero?” One of his fellow cops breaks in loudly, while grabbing Oleksandr by the shoulder. “He was arrested by the (Russians) and interrogated. Come on, tell him.”

Oleksandr’s heroics had not been under discussion. The conversation was about collaborators in Kupiansk District, during and after the occupation, which ended in September 2022. These included the former mayor of the city, as well as multiple local authorities and residents who were made into “authorities” by the Russians during the occupation. That included multiple Kupiansk police officers.

After liberation, Oleksandr returned to his job in the town. He and his fellow police now mainly have two types of crimes to deal with: collaboration and looting. With the population down from 28,000 to 11,000 people, looters see all the things left behind to be up for grabs. (On Aug. 10, the order was announced to evacuate the Kupiansk District residents from threatened areas.)

Collaboration is a more insidious threat. Its consequences range from a minor spread of Russian propaganda to people getting killed.

When apprehended, alleged collaborators from the days of the occupation often say that they had been forced to do it with threats and violence. A Kupiansk police investigator, Andrii Subotin, dismisses that as a bad excuse.

“For those who made the decision to remain in Ukraine and stay true to their oath, that was all possible. It was possible to leave,” Subotin told the Kyiv Independent. “When people say ‘there were no ways out so I swore an oath to the Russians,’ I don’t buy it. I left the occupation twice and remained faithful to my duty.”

When his colleague Oleksandr is worn down enough to tell his story, it reveals that indeed, a clever and determined person could leave the occupation zone with some effort. But when you’re a hunted man, that’s sometimes easier said than done.

Invasion begins

Oleksandr had retired from his police job shortly before the Russian military buildup began along the border, some 20 kilometers away from Kupiansk, where he lived with his wife, two daughters and their pets.

When they struck on Feb. 24, 2022, the Russians rolled over the area easily. Mayor Hennadiy Matsehora welcomed the Russian army and set about helping the occupiers get settled in.

Residents of Kupiansk suddenly had very urgent decisions to make. And as Russians fired on refugee columns throughout the country, escaping became a chancy endeavor. Oleksandr and his family stayed in the occupied city.

Oleksandr told the Kyiv Independent that in the early days of occupation he was passing information about Russian vehicle movements to Ukrainian forces defending Kharkiv through his contact, the regional prosecutor.

With the occupiers in charge, it was not long before the arrests began.

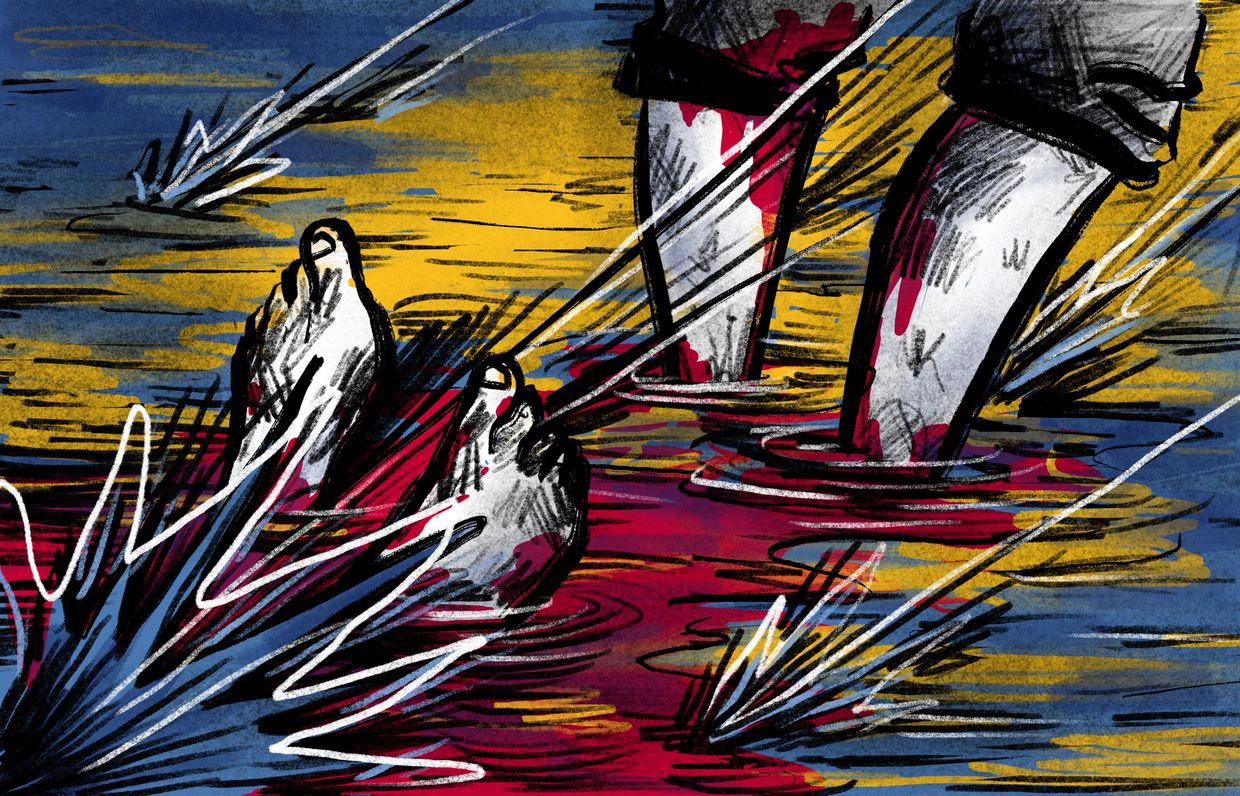

In early March, they came for his upstairs neighbor — Oleksandr heard them breaking down his door at 7 a.m. Soon, they came for him. He was thrown to his knees in front of his family and a bag was placed over his head.

Russian hospitality

He was moved to an unheated basement at below freezing temperature and beaten before being loaded into a truck and sent to Belgorod Oblast across the border. Eventually, he was brought to a POW camp in Shebekino, a Russian city a two-hour drive from Kupiansk, with three parallel barracks and rows of bunks against their walls. Each had a single potbelly stove in the middle, but the supply of wood to the prisoners was strictly rationed, barely enough to keep it smoldering through the night.

From the middle barracks, he was taken to a more secluded location. “And then we interacted,” he said.

The clinical word ‘interacted’ puts one in mind of the thin tang of antiseptic covering the stench of gore. In prior interviews with interrogation victims, they said the ‘interaction’ often involved the application of electrical current.

Oleksandr didn’t get shocked, but he was beaten and suffocated. Sometimes, he said, they’d douse his leg in flammable fuel, then set it on fire and quickly put it out. They also threatened his family, saying nothing was stopping them from seizing them any time they wanted.

By day three of this treatment, he figured out that they didn’t just want to hurt him or learn what he knows. They wanted to turn him to their side, to work for the Kupiansk occupation authorities. So he agreed to cooperate.

“I tricked them,” he said. “Told them that I agreed to work together.”

Unbeknownst to him at the time, his brother went to the turncoat mayor of Kupiansk, to personally ask for mercy for Oleksandr. The captured officer’s wife also tried to persuade the Russians to go easy on him.

Pressure from the mayor likely sealed the deal and Oleksandr was driven back across the Kharkiv border. He heard the soldiers passing city initials. “For a moment, they said something about taking someone towards ‘I’ and I was terrified that they’d turn towards Izium,” he said.

But then he felt the familiar slope of the road beneath the vehicle and knew he was back in Kupiansk, where he found himself in another torture chamber.

“I asked them why are you doing this, I already agreed to cooperate,” he said. “One of them says ‘wait, really? Hold on, I’ll go check.’” While he checked, his partner inflicted more pain on Oleksandr for about 20 minutes, until the other man returned. “Shit, he’s right. Why is the mayor stumping for you?”

The occupiers returned his seized Ukrainian documents in a little bag and ordered him to check in with them every week and wait around until the new administration was sufficiently built up for him to work there. Oleksandr is a resourceful man, with many contacts in the area, who could have been a big asset if they could turn him, and a bigger liability if they failed.

Easter escape

Unfortunately for the Russians, Oleksandr was back to his old tricks in no time. After sending his wife and daughters away to Germany, via Poland, he was again skulking about, trying to report Russian mechanized movements to the Ukrainians.

He was also secretly meeting with other remaining law enforcers and members of the justice system and trying to persuade them not to work for Russia. Many were considering collaborating and some ultimately did.

Oleksandr described days of moving from tree to tree, hiding out on remote farms and sneaking into his apartment at 4 a.m. to feed the pets they left behind – a fish and his daughter’s white chinchilla named Pushok (Fluffy).

When the mobile communication blackout hit the area on April 7, he knew he had to get out of there. He’d need a good story to feed the Russian checkpoints standing between him and the unconquered lands. And he knew one date was coming up that offered up a perfect opportunity: April 24, Orthodox Easter.

Oleksandr and people he trusted arranged for several cars to be filled with mixed passengers, including women and children, who would pretend to be making holiday visits to a neighboring town. Because of bad communication between the inner and outer checkpoints, they had a good chance of getting away with the ruse.

Oleksandr’s hopes were nearly dashed the night before the trip when he found the note pinned to his front door, summoning him to the district center tomorrow.

If the checkpoint was told to watch for his name, the risk to the other passengers was too great. Oleksandr sent them off without him but watched the checkpoint from a hiding place within view. When the cars, staggered half an hour apart, passed through, he saw that the soldiers did not look to be checking for specific names.

He still had a shot. But he had less than a day to come up with something believable.

He needed more people in the car with him. He found a young guy and a disabled girl, who would pretend to be a couple traveling together. Then he went to his in-laws and asked them to get ready in 20 minutes and take nothing with them, to sell that this was a brief visit.

“The first checkpoint was the scariest,” Oleksandr said. “But then we got lucky.”

The car reached the checkpoint in the pouring rain. An irritated soldier who wanted to get out of the water briefly checked them over and tried to contact someone on his walkie talkie. It didn’t work. The soldier waved them through.

The next few checkpoints were easier, as they were out of communications range from the town and no one would be calling them to give Oleksandr’s description once he failed to show up for his summons.

The group used their intimate knowledge of the local side roads to go around most of the guarded areas, until they began approaching Balakliya. There, Oleksandr’s phone caught a connection and he called the regional prosecutor, with whom he had been working since the full-scale invasion began.

“He told me that Balakliya was too dangerous, with Buryat soldiers reportedly firing on evacuees,” Oleksandr said. But he decided to go for it, under a new cover story. He would tell the Russian troops that they were visiting his brother who was dying in a hospital in Poltava after getting into a road wreck. In reality, that brother had already died in the past.

But the fear kicked up as they reached Balakliya, unsure of whether the ruse would work. The soldiers asked him if he would be coming back, and he emphatically said that he would.

“Look, I’m registered in Kupiansk, my wife and daughters live there too,” he said, showing them his documents. “I’ll just be a few days.”

They wrote down his information and let them through. The next checkpoints they encountered were Ukrainian. He was soon bustled into a debriefing, where he pointed out all the locations where he saw concentrations of Russian vehicles.

In early September, when the Kharkiv counteroffensive was underway and Oleksandr was coming back to the liberated Kupiansk, he said he saw the remnants of the HIMARS strikes on the coordinates he provided.

Now he’s back at his job, policing Kupiansk and talking to his family long-distance, even as shells continue to fall on the city and pro-Russian residents bide their time, hoping for the tides to change.

But Oleksandr has a friend to keep him company. While the fish didn’t survive the cold, Pushok the chinchilla made it and now lives with him.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Igor Kossov, I hope you enjoyed reading my article.

I consider it a privilege to keep you informed about one of this century's greatest tragedies, Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine. With the help of my colleagues, I will continue to bring you in-depth insights into Ukraine's war effort, its international impacts, and the economic, social, and human cost of this war. But I cannot do it without your help. To support independent Ukrainian journalists, please consider supporting us. Thank you very much.