Ukrainian artist Liubov Panchenko died after month of starvation in Russian-occupied Bucha

One cold day in late March, a Russian shell hit a small barn behind an unremarkable two-story house in then Russian-occupied Bucha in Kyiv Oblast.

The powerful blast partially destroyed the barn, broke the house's windows, and cracked the entrance door, letting out a small black dog. It rushed down the empty street barking loudly, as if calling for help.

Drawn by the noise, a local resident went outside, despite the fear of being killed by Russian soldiers. He followed the barking dog up to the site of the recent explosion.

There, inside the dilapidated house, a man found an old lady lying unconsciously in the cold room.

The woman was Liubov Panchenko, a renowned Ukrainian artist of the 1960s.

Panchenko spent her whole life defending and promoting Ukrainian culture, resisting the Soviet totalitarian regime’s censorship by adding folk motifs to her drawings, collages, and clothes as well as speaking the Ukrainian language when forbidden.

For that, she was repressed as an artist. While her work was shown alongside other contemporaries, Panchenko never had her own individual exhibit until after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

And for being Ukrainian, she was killed. Russia’s war caused her to slowly die of starvation in her beloved hometown of Bucha, where Russian troops killed at least 412 people during the town’s occupation in what is now known as the "Bucha massacre."

Isolated from the whole world, the 84-year-old artist spent a month under Russian occupation alone, sharing what little food she had with her dog Bonia.

Soon after being found, local volunteers took Panchenko to a hospital in Kyiv, where for nearly a month doctors tried to save her life.

"What we saw at the hospital was a skeleton covered with skin," says the head of the Ukrainian Sixtiers Dissident Movement Museum Olena Lodzynska, who knew Panchenko personally.

"She was beyond exhausted," Lodzynska adds.

The artist never recovered. On April 30, Panchenko died in a hospital in Kyiv.

“She was not broken by the KGB during Soviet times,” said Ukraine’s first lady Olena Zelenska. “But the Russian occupation broke her.”

‘All for art’

Russia's war wasn't the first Panchenko witnessed. Born on the eve of World War II to a Ukrainian family living in the now non-existing village of Yablunka near Bucha, Panchenko experienced the hunger and struggles of that time during her childhood.

But even in such dark times, little Liuba was eager to create and started drawing soon after learning to hold a pencil.

But the older Panchenko got, the more her parents worried about her aspirations of becoming an artist. “They did not understand how she would earn a living,” says Igor Kulyk, the head of Ukraine's Archive of National Memory.

When she entered the embroidery department of the Kyiv School of Applied Arts in the early 1950s, Panchenko had a hard time surviving on a small scholarship as her only source of income.

"She was starving severely back then," Kulyk says.

Panchenko’s hunger resulted in severe dystrophy, long-term hospitalization, and a complex surgery.

"And all for art," says Kulyk.

Soon after recovery and graduation, Panchenko’s desire to improve her skills as an artist led her to study graphics at a newly-opened branch of the Lviv Polygraphic Institute in Kyiv, where she mastered linocut, a printmaking technique, as well as created illustrations for Ukrainian songs and poems.

Combined with her phenomenal talent, the education she received helped Panchenko establish her distinguished style — the artist's own sui generis twist on Ukraine's folk motifs.

"She knew many techniques and wasn't afraid to use and combine them," says historian Liubov Krupnyk, who also knew Panchenko personally.

"She didn't repeat but creatively rethought traditional Ukrainian elements," says Lodzynska.

But it was also the community she was part of that helped Panchenko cultivate her love for Ukrainian culture, Krupnyk adds.

Guilty for being Ukrainian

During one of Russia's multitudinous attempts to silence Ukrainian identity during the Soviet era, Panchenko joined Kyiv's Creative Youth Club, which united a new generation of creative Ukrainian youth who opposed the Soviet authorities known as the Sixtiers.

“It was an attempt of those who just wanted to speak Ukrainian and talk about Ukraine, to gather in one place and do it,” Kulyk says.

Inspired by this community, Panchenko started making traditional folk outfits for Ukrainian choir members and embroidered shirts for her friends and drew portraits of legendary poet Taras Shevchenko adorning them with his iconic quote from the "Caucasus" poem — “fight and you will win.”

By that time, Panchenko's parents finally accepted their daughter's decision to be an artist and their house in Bucha became a welcoming harbor for Ukrainian caroling groups, banned by the Soviet authorities.

"It was the environment that shaped her worldview," Krupnyk says.

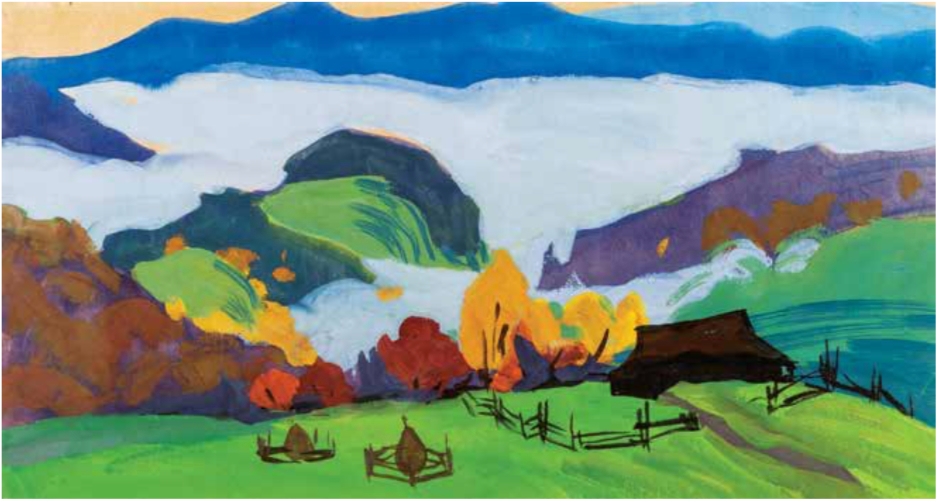

It was also the time when her talent blossomed: In the mid-1960s, Panchenko created an astonishing series of watercolor drawings depicting the Ukrainian Carpathian Mountains and her native Kyiv Oblast, as well as sketches from her trip to the Caucasus.

As a clothing designer, Panchenko weaved modern style with traditional folk elements, also using the scraps of fabric to make collages.

Though her works were not totally banned by the Soviet authorities — many of her fashion sketches and embroidery were published in the popular “Soviet Woman” magazine with approval of the magazine’s management — Panchenko was often criticized and was even asked to "change the style of her works."

“When some Soviet minister told her that it was the time to change her style, she told him that maybe it was the time to change the minister,” says Lodzynska.

“She was quite a straightforward person, she always said whatever was on her mind,” says Sofia Rozumenko, Kyiv graphic designer and illustrator who is behind the project "60s. The Lost Treasures" that spotlights Ukrainian artists of the 1960s. Rozumenko's grandfather was also a good friend of Panchenko.

“That's why she had problems with the Soviet authorities.”

Panchenko refused to join the Union of Artists of Ukraine, saying that its members were "dancing to the tune of Soviet authorities, and she was dancing to her own."

The artist didn’t have a single personal exhibition up until 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union.

"For them, she was guilty of being Ukrainian, for being born in Ukraine, for considering herself Ukrainian and promoting Ukrainian (culture)," Kulyk says.

Killed by Russia

Ever since the death of her husband, Ukrainian artist Oleksiy Oliinyk, in 1994, Panchenko lived alone in her hometown Bucha, occasionally visited by her friends and relatives.

She never had children due to her weak health, which continued to decline over the years. By the time Panchenko turned 84 on Feb. 2, she was "almost helpless and needed constant support," says Krupnyk, who visited the artist on her birthday to present the first digital collection of her work.

“If it wasn't for these inhumane conditions during the occupation of Bucha, I think she would still be alive to witness the print version of the album," Krupnyk says.

On the day Russia started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, Panchenko's relatives managed to bring her some food, says Lodzynska. Rozumenko says that before the war, mainly local social workers would bring Panchenko food.

When Russian troops entered and occupied the town, violently killing civilians en masse, it became clear that leaving one’s home could be a death trap. It was no longer possible to get to the artist's house.

Her beloved dog Bonia was Panchenko's only companion.

"How she was surviving and what she was eating is still a mystery," Lodzynska says.

Only after her courtyard was hit by a Russian shell, days before Kyiv Oblast was liberated, already unconscious Panchenko was found at her home and then hospitalized.

Unable to identify her at the hospital, Lodzynska only found her around two weeks after she was hospitalized.

"She looked just like the victims of concentration camps: Sunken cheeks, thin arms and legs," Lodzynska says.

Even though Panchenko was awake, the doctor told Lodzynska she wasn't reacting to anything and was getting nutrition intravenously. But when Panchenko saw the flowers in Lodzynska's hands, she instantly reached for them.

"She said 'I’m very glad, but sorry that I’m not in a good state,’” Lodzynska recalls. "As if giving away all her energy with these words."

In the following days, Panchenko started eating little by little, sparking hope she would survive.

Barely talking, she told Lodzynska that Russian soldiers tried to enter her house one day, but she did not let them in. The rest is still unknown.

On one day in late April, one of Panchenko's friends came to visit her at the hospital. She was deep in her sleep, according to Lodzynska.

"Her doctor said she had been sleeping for two days by then," Lodzynska recalls.

"She never woke up."

There, in a regular general ward of a Kyiv hospital, full of other victims of Russia’s war, Panchenko died on April 30.

"She was killed by Russia," says Kulyk. "But her legacy will live on."

In memory of Panchenko, the Ukrainian Sixtiers Dissident Movement Museum will reopen with the exhibition of her artworks as soon as the war ends.