Trump takes aim at Putin’s oil lifeline — China and India still hold the key

(L-R) Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Indian President Narendra Modi, during the BRICS Leaders’ Summit in Kazan, Tatarstan Republic, Russia, on Oct. 23, 2024. (Contributor / Getty Images)

Russia's oil exports to China and India are a lifeline, fueling Moscow's war effort. Experts say now there is a chance to cut it.

Over the past decade, revenues from oil and gas have accounted for 30–50% of Russia's budget, roughly equating to the amount Moscow spends on its all-out war against Ukraine.

After an exhausted back and forth, U.S. President Donald Trump has been set to change that. His latest move — sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil — has prompted Moscow's top oil buyers to rethink their strategy of buying Russian energy in bulk at a lucrative discount.

Experts told the Kyiv Independent that the sanctions "can certainly be efficient," but the real test lies ahead: Will China and India stop their purchases, and what can actually be done to enforce them?

Oil lifeline

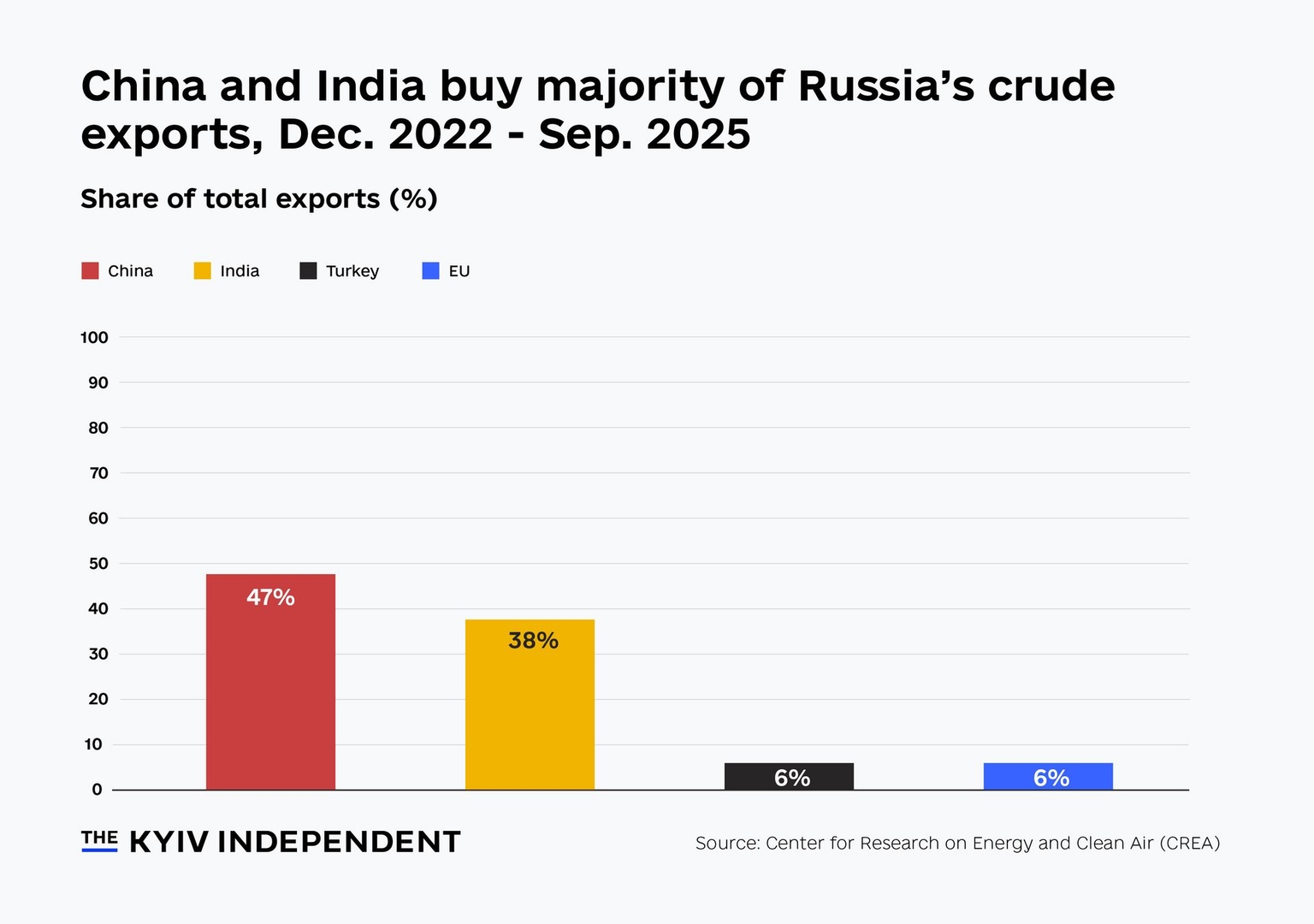

The scale of China and India's oil purchases is staggering.

New Delhi and Beijing turned to Russian oil after its value plummeted following the Western initial sanctions push in 2022.

Last year, China bought over 100 million tons of Russian crude oil, making up nearly 20% of its total energy imports. Oil exports to India, which were marginal before the start of the all-out war, now account for $140 billion.

From Dec. 5, 2022, until the end of September 2025, China bought 47% of Russia's crude exports, followed by India with 38%, according to an analysis by the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Turkey and the EU each bought just 6%.

Together, the two Asian giants make up 85% of Russia's total oil exports.

Trump's tariff gambit

For months, Trump has oscillated between confrontation and caution toward Moscow.

In the summer, the U.S. president floated the idea of imposing tariffs on nations purchasing large amounts of Russian oil to pressure Moscow into meaningful negotiations with Ukraine.

In simple terms, if countries like India continue buying Russian oil, they could face tariffs of up to 100% on exports to the U.S., which might raise pressure on Indian exporters.

In August, the U.S. president followed through with his promise, imposing a 25% tariff on exports from India as a "penalty" for its Russian oil purchases, taking overall duties to 50%.

"They have always bought a vast majority of their military equipment from Russia, and are Russia's largest buyer of energy, along with China," Trump said on July 30.

Just a day after Trump's announcement, Reuters reported that Indian state refiners had halted Russian oil purchases. Bloomberg wrote that the Indian government instructed oil companies to prepare plans for alternative supplies.

But by Aug. 20, India's state-owned refiners had quietly resumed purchases of Russian oil.

"India buys over one-third of its oil from Russia; before the full-scale invasion, it was buying a fraction of that," said Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Finance and Security at RUSI. "So India can clearly reduce its reliance on Russian oil if it wants to."

Shifting strategy

Although Trump didn't carry out his threat to target China, he increased pressure on Russia's oil industry in October by sanctioning the country's two biggest oil companies — Rosneft and Lukoil.

The measures freeze all U.S.-based assets belonging to those companies and, more importantly, open the door to secondary sanctions against foreign institutions handling their transactions.

This time, the impact appears more serious.

According to Bloomberg, India's largest refineries are now planning to reduce purchases from Rosneft and Lukoil to nearly zero. Reuters reported that Chinese state-owned oil firms have suspended seaborne Russian crude imports over fears of U.S. penalties.

On Oct. 27, Russia's Lukoil also announced that it plans to sell its foreign assets.

Wojciech Jakobik, an energy security analyst and host of Podcast Energy Drink, told the Kyiv Independent that this move already demonstrates the effectiveness of Trump's latest measures.

"We can already see that U.S. sanctions are effective when Lukoil announces that it wants to sell all its foreign assets," Jakobik said. "The threat of secondary sanctions needs to be credible, so it depends heavily on actual enforcement."

David Goldwyn, a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council, said that while the Trump administration's statement warns that institutions importing Russian oil "run the risk" of secondary sanctions, its language remains cautious.

While the expert noted that India seems prepared to adjust its market strategy, he added that China remains "another matter," suggesting Beijing is less likely to follow.

"The (U.S.) administration has not imposed secondary sanctions on China for its importation of Russian or Venezuelan crude," he said. "So far, there has been no mention of Russian crude purchases in U.S.-China trade talks."

Keatinge said the threat may initially serve as a deterrent.

"To be truly effective, the U.S. will need to follow up with supplementary designations of entities involved in continued Russian oil trade in order to ensure that the impact is lasting," he added.

The expert said he doubts the countries will completely halt Russian oil purchases, but said "certainly in the case of India, it can be hoped that they reduce their buying dramatically."

Can the strategy hold?

Not all experts are convinced the effort will stick.

Ellen Wald, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, said that while the sanctions may cause India and China to reassess their purchases, they are unlikely to stop entirely.

"Some refineries will likely decide to cut back on the total amount of Russian oil they have been importing, but neither of these countries will halt their imports of Russian oil based on a threat," she said.

Vladimir Dubrovskiy, a senior economist at the Center for Social and Economic Research Ukraine, said Russia has spent years perfecting ways to hide its oil sales behind intermediaries and the "shadow fleet."

"I'm afraid that its impact would, at best, be short-lived," he said. "(Russia) can also easily find numerous smaller buyers who are unconcerned about trading outside the U.S. dollar system."

He noted that previous tariffs on Indian exports had "no noticeable effect," while China and Turkey remain unlikely to scale back Russian purchases for geopolitical and economic reasons.

Trump's tariff threats toward China, Dubrovskiy added, are "largely futile." Beijing, he said, wields too much leverage — and higher tariffs would only raise prices for U.S. consumers.

"Trump has effectively backed away from this approach by insisting that the European Union impose such sanctions first, with the U.S. only following thereafter," he added.

Former EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom said the measures "can certainly be efficient" but questioned whether they alone could shift Chinese or Indian behavior.

"Whether India or China will stop buying is another issue," she told the Kyiv Independent, noting the matter could arise at Trump's Oct. 30 meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

What the West can do

While experts agree that threatening Russia's vital income source makes sense, they argue that tactics need adjustment for the strategy to truly work.

"If China continues to import Russian seaborne crude, even at a discount, it will undermine the efficacy of the sanctions and, ironically, help subsidize the Chinese economy," Goldwyn said.

Western countries need to offer China and India alternatives to Russian oil, Keatinge argued — whether through Middle Eastern supply deals or expanded U.S. exports.

Wald said for the measures to have a real impact, the U.S. will need to enforce secondary sanctions.

"The U.K., EU, and the U.S. would have to levy fines against Indian companies that import Russian oil and bar these companies from doing business with other businesses domiciled in the U.S., U.K., and EU," she told the Kyiv Independent.

"This is the only way to truly show India and China that they are serious about sanctioning Russian oil and cutting off Russia's revenue."

Dubrovskiy believes a truly effective solution would be to strengthen the oil price cap, which sets the maximum allowable price for Russian seaborne oil exports, and to close the Baltic straits to Russia's "shadow fleet" tankers on ecological and safety grounds.

He suggested restricting insurance coverage to sales made only to a vetted list of buyers not affiliated with Russia.

"These buyers would contribute half of their discount to a special fund supporting Ukraine," Dubrovskiy said. "The price cap should then be gradually reduced so that, within a few months, it falls to $30 per barrel or less."

This would keep Russian crude flowing to global markets and prevent price spikes while cutting off key revenue streams feeding Moscow's war budget and covert activities abroad, he said.

Some European countries are already moving in that direction. Denmark announced on Oct. 6 that it would tighten controls on tankers passing through its waters — focusing on older ships often used by the shadow fleet — citing environmental and safety concerns.

The current price cap is flexible but is set at $47.60 per barrel.

Malmstrom said that individual action won't be enough. Europe and other allies should further coordinate their own sanctions regimes and the monitoring of them, she added.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Tim. The author of this article. Thank you for taking the time to read it. At the Kyiv Independent, we speak to top experts to bring you accurate, in-depth reporting.

We don't have a wealthy owner or political backing. We rely on readers like you to support our work. If you found this article interesting, consider joining our community today.