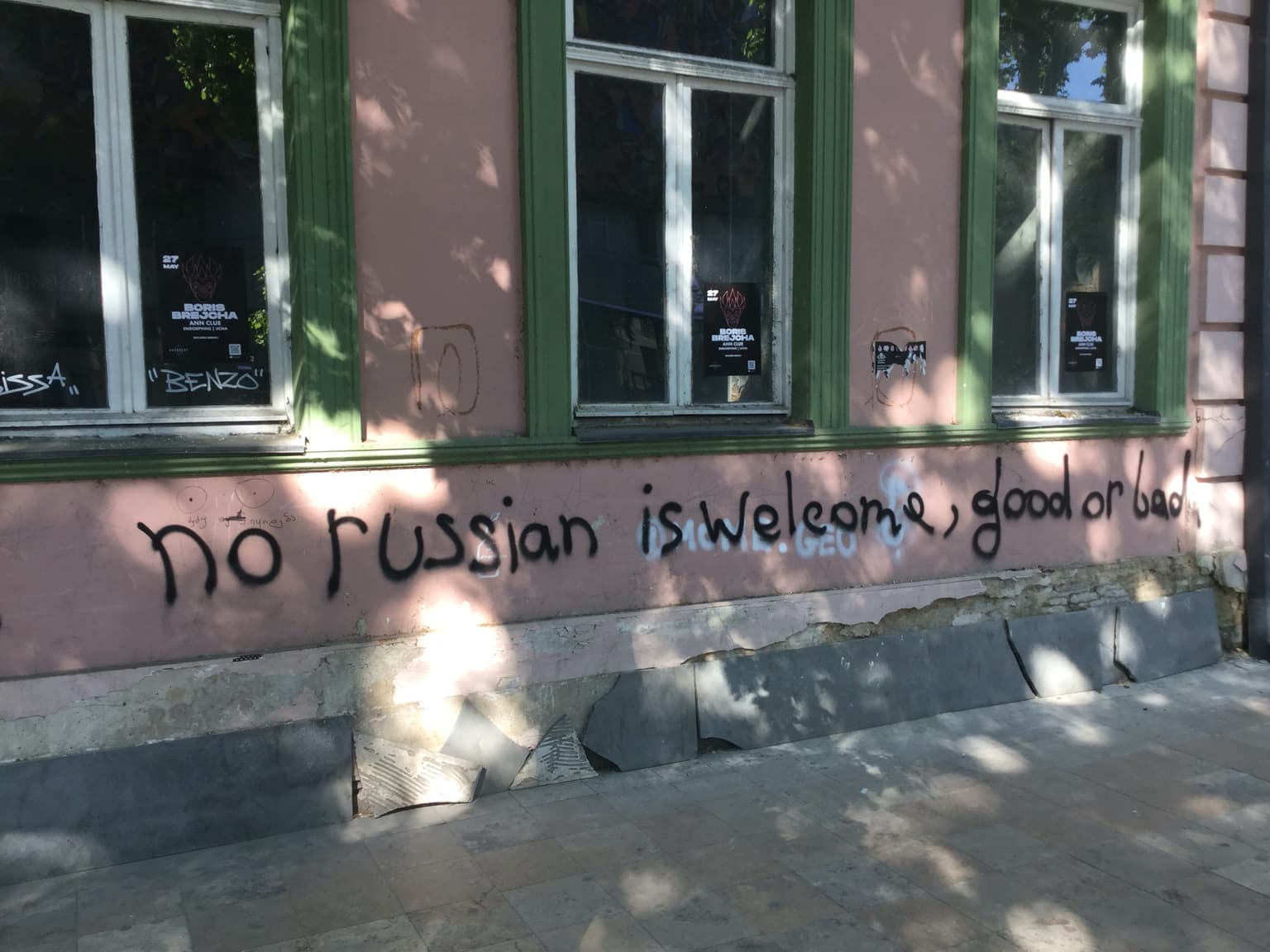

A bloodied shirt, tattered pants, leather shoes sliced open and flesh shaved off by razor-wire are what I endured while getting a closer look at South Ossetia, a Russian-occupied region of Georgia. This rendering took place under the gaze of a nearby Russian watchtower, whose inhabitants thankfully chose not to sally forth. Meanwhile their Georgian counterparts, deployed further back from this sleepy borderline, patrolling a once-important regional highway now little more a weed-covered strip of broken asphalt, were only slightly more curious. Yet, like every Georgian I met, they expressed great sympathy for Ukraine on learning that I was a visiting Canadian professor of Ukrainian heritage. Having suffered a Russian invasion in August 2008, and the subsequent amputation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, their country stands with Ukraine, especially as Ukrainians confront the genocidal agenda of Vladimir Putin, the KGB man in the Kremlin. The prevailing sentiment in Georgia was well-captured by graffiti I photographed on a Tbilisi wall: "No Russian is welcome, good or bad."

Earlier that same day I explored another site along the occupation line, near the village of Odzisi. Once home to some 90 families, their number is now reduced to perhaps a dozen households, mostly people too old or too obstinate to leave. By chance we met a man tending his cows who immediately invited us into his home, treating our party to a generous mound of fresh honeycomb, cherry juice and multiple shots of home-brewed brandy, our toasts celebrating the solidarity between Georgia and Ukraine and always prefaced by the phrase, Gaumarjos! (meaning Victory to You!). It could not have been more genuine. And here, as elsewhere, the Georgians kept apologizing, explaining that, as a smaller state, and still under threat, they can't do more against Russian imperialism. Still, unambiguously, they stand with Ukraine.

As I wandered about I was also reminded of how this latter sentiment is not simply a response to Russia's war against Ukrainians. A monument was unveiled in Tbilisi 15 years ago, even before Russia attacked Georgia or Ukraine. It portrays Prometheus. While I wasn't expecting to find him here, perhaps I should have been, having earlier glimpsed the mountains of the Great Caucasus range on the distant horizon. Amongst those 'Mountains of Scythia' I could just discern the tallest peak, Mount Kazbek. When I was a boy I was enthralled by Hellenistic myths and, in particular, by the tragic story of Prometheus, the Titan who created man out of clay and defied Zeus by stealing fire from the gods, giving humanity a chance not just to survive but to prosper. For that Prometheus suffered the most terrible of tortures. Chained to a mountain - was it Mount Kazbek? - he was ravaged daily by an eagle, a predator that tore out his liver (which the ancient Greeks believed was the seat of human emotions). It would then regenerate, dooming Prometheus to endure the very same agonies the next day, to continue for eternity.

This statue was never, of course, intended as just a fanciful portrayal of a Greek myth. The then-presidents of Poland, Lithuania, and Georgia attended the 2007 unveiling. They quite certainly understood what was being evoked. For this statue was intended to recall, perhaps even to rekindle, the Promethean League, a movement begun in 1925 to rally nations threatened by Moscow, particularly Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkestan, the Mountaineers of the Northern Caucasus, the Crimean and Volga Tatars, the Don, Kuban, and Terek Cossacks and the peoples of Finland, including those from Ingria, Komi, and Karelia. This League was shaped by the great interwar Polish leader, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, who assuredly understood the etymology behind the name Prometheus (coming from the Greek words meaning foresight). Trying to anticipate the future, Piłsudski's plan sought to organize a common defence against Russian imperialism including countries stretching from the Baltic to the Black and Caspian seas. While this Promethean vision was not realized it, like most good dreams, geopolitical or otherwise, was never entirely forgotten. In our time many of these very same countries and nations - Ukraine, the Crimean Tatars, Finland, Poland, the Baltic states and Georgia, understand how Putin's drive to restore a "Great Russian" imperium represents a clear and present danger to their existence. Once the Russian war against Ukraine has ended - and Ukraine must win - Europe's post-war security architecture will have to be Promethean-inspired, foresight finally unbound.