Why European elections matter for Ukraine

Franch President Emmanuel Macron (R) kisses European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen as he welcomes her to the Élysée Palace ahead of trilateral talks with Xi Jinping of China on May 6, 2024, in Paris, France. (Kiran Ridley/Getty Images)

Starting on June 6, citizens of the European Union will head to the voting booths to elect the bloc's 720-member European Parliament.

The election, held between June 6 and June 9 and often downplayed as irrelevant by voters, will have a major impact on EU domestic and foreign policy, among them the union's dealings with Ukraine.

Ukraine awaits the start of membership talks, and the allocation of EU funds that are a crucial lifeline for the country amid Russia's war.

Surging right-wing populist parties, Russian interference scandals, and the creeping Ukraine fatigue are a source of modest anxiety in Ukraine ahead of the vote.

Members of the European Parliament (MEP) shape and approve legislation, giving them sway over the EU budget and foreign aid, and approve candidates for the European Commission, the bloc's executive arm.

While the growing popularity of right-wing parties represents a challenge, experts do not expect a major shift in Brussels' policy.

"I would imagine we're still going to see quite strong support for Ukraine in terms of military and economic aid," although it could be "slightly diminished," said Amanda Paul, a senior policy analyst at the European Policy Center (EPC), in a comment for the Kyiv Independent.

Opinion polls show good results for right-wing and far-right candidates, but the center-right European People's Party (EPP) remains the projected victor.

Even though European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, supported by the European People's Party and seeking to renew her term, might foster alliances on the right to secure reelection, she made it clear that any coalition with Kremlin-friendly forces is out of the question.

Finally, the national-conservative European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) factions might be of the same mind when it comes to environment and migration but face wide differences when foreign policy issues arise.

The surging Right

EU citizens will decide by the end of this week who will fill the 720 seats of the next European Parliament.

The number of MEPs is divided among member states proportionately. For example, Germany, the largest country, currently has 96 lawmakers, while Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Malta have six each.

Most of the MEPs group themselves into parliamentary factions centered around policies and ideologies. The EPP and the center-left Socialists & Democrats have long dominated the parliament and are still projected to finish first and second, accordingly.

The growing challenge coming from the right, however, including parties with a history of admiration for Russia and Vladimir Putin.

Some of the polls show that candidates of the national-conservative European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) factions, as well as non-affiliated right-wing politicians, could together gain close to one quarter of the seats.

Until recently, polls showed ID coming in third place with the chance to almost double the number of MEPs from 49 to almost 90. The faction dropped to fifth place after it kicked out Alternative for Germany (AfD), leaving the ECR to compete for the third spot with the liberal Renew Europe faction.

The ECR's top players, like Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy (FdI) or Poland's Law and Justice (PiS), may find common ground with the far-right on migration or environment but have largely closed ranks with the moderates when it comes to supporting Kyiv.

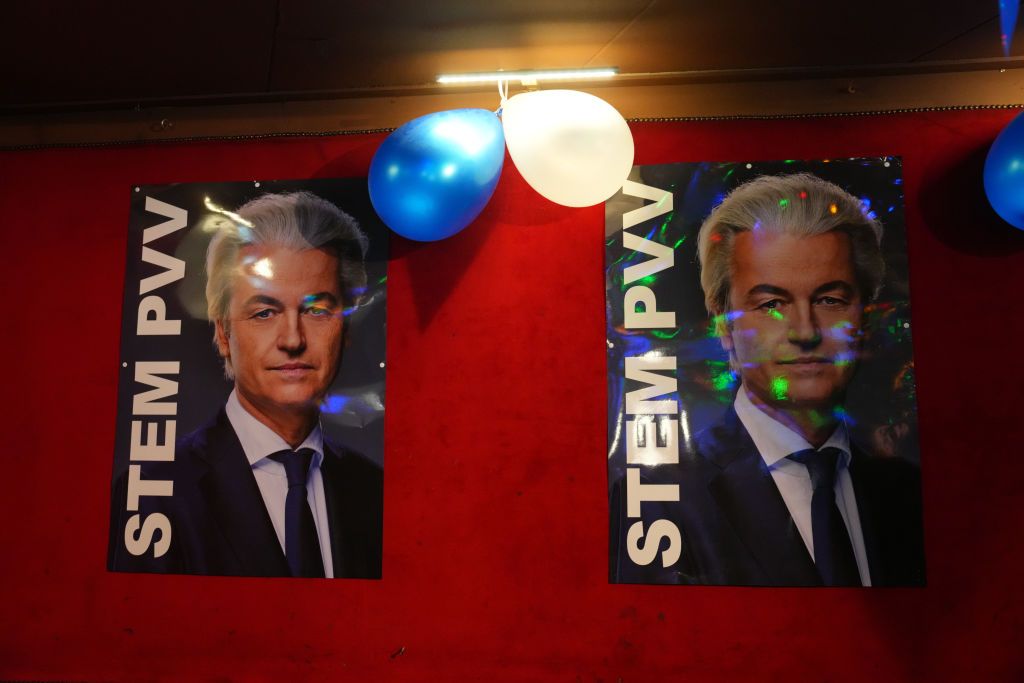

In turn, the ID is composed of parties traditionally seen as close to President Vladimir Putin, including Matteo Salvini's Lega (League), Marine Le Pen's National Rally (RN), Geert Wilders's Party for Freedom (PVV), and formerly the AfD.

Despite that, creeping Ukraine fatigue has not come to the forefront of the far-right parties' campaigns, which focus instead on migration and environmental policies.

Some of these parties have even begun to pay at least lip service to Ukraine following the outbreak of the full-scale war, seeking to cast off the burdensome image of having Kremlin ties.

In an address to the French parliament in March, Le Pen praised "the heroic resistance of the Ukrainian people that will lead to Russia's defeat." The incoming Dutch government, led by Wilders's PVV, affirmed the Netherlands' continued support for Kyiv.

Yet, Le Pen's party still abstained in a vote on the French-Ukrainian security pact, while Wilders and Salvini both criticized military support for Ukraine during the full-scale war.

There is a notable trend among many on the far right to cast off the most controversial and polarizing positions to appeal to a broader electorate.

This was also among the reasons why Alternative for Germany (AfD) was kicked out from the ID group following a series of scandals that included its candidates speaking positively about the Nazi SS or being investigated for receiving cash from Moscow.

In March, discoveries by the Czech authorities launched investigations that implicated several politicians, including AfD lawmaker and European Parliament candidate Petr Bystron, in allegedly being paid by pro-Russian agents.

Finally, aside from both the ID and the ECR, Hungary's Viktor Orban remains the eternal maverick.

Fidesz's MEPs have been sitting as non-inscrits (not affiliated with any group) since the party left the EPP in 2021 due to the former's growing radicalism and illiberal views.

Hungary has also been consistently the most Kremlin-friendly country throughout the full-scale war, repeatedly blocking aid to Ukraine and sanctions against Russia.

Orban has been seeking to find a new home for his party, namely by courting the European Conservatives and Reformists and Meloni. He has also backed Le Pen's proposal to form a broader right-to-far-right political camp in the parliament.

Such a coalition would be inevitably strained by internal conflicts sparked by polar views on Russia's war against Ukraine, threatening to drive more moderate MEPs away and making it a less likely coalition partner for the leading European People's Party, Politico writes.

Why the elections matter for Ukraine

The European Parliament is one of the EU's three core institutions. Together with the EU Council, it amends and approves legislation proposed by the European Commission.

The parliament cannot propose legislation directly but can ask the commission to do so. It approves or vetoes the European Commission's president and commissioners, helping to shape the makeup of the bloc's executive.

The EU's budgetary policies are also heavily influenced by the parliament's decisions. The MEPs' votes help define the union's financial priorities, approve long-term budgets, and scrutinize how the money is spent.

A right-ward shift "will have some implications on some legislation… including issues related to Ukraine," primarily when it comes to the budget, Amanda Paul, from European Policy Center, said.

The EU is the single largest donor of non-military aid to Ukraine, and its mid-term revision of the 2021-2027 budget included a four-year package of 50 billion euros ($54 billion) in grants and loans for Ukrainian needs.

As a key player in Ukraine's recovery, the EU has sought to introduce to foster reconstruction efforts, working with Kyiv to rebuild its infrastructure with an eye on the environment and sustainability.

The synergy of Ukrainian reforms and the European funds under the Ukraine Facility is meant to help Kyiv reduce industrial pollution, push down carbon emissions, and move away from the resource-based economy. These step should help pave Ukraine's path toward the eventual accession.

Such plans are likely to come under heavy scrutiny if right-wing parties gain a stronger position in the parliament. The fight against supposedly "ideologically motivated" green policies has shaped up to be one of the key topics in the right and far-right election campaigns.

"In a more sanguine scenario, only implementation timelines and goals relating to, for example, emission targets might be affected," Niklas Ebert writes in an analysis published by the German Marshall Fund.

In the worst-case scenario, it could lead to reduced funding for such projects as sustainable housing or the development of renewable energy sources, Ebert adds.

Overall, the experts do not expect a major turn in the policy toward Ukraine, however. The military and economic aid will likely continue, even though it could decrease somewhat under a more right-wing parliament, Paul said.

Another key role that the parliament plays is in shaping the composition of the European Commission.

While the members of the executive arm are proposed by the European Council – the 27 heads of states and governments – parliament must sign off on the candidates.

It is the commission that represents the EU on the global stage, oversees the union's day-to-day functioning, and plays a key role in the bloc's foreign policy, including enlargement.

For Ukraine, an important question is who is going to fill the role of the European Commissioner for Neighbourhood and Enlargement, currently occupied by Orban-proposed Hungarian Oliver Varhelyi.

How is the position filled will signal the bloc's future approach toward enlargement, said Liubov Akulenko, the executive director of the Kyiv-based Ukrainian Center for European Policy, in a comment for the Kyiv Independent.

"If (the enlargement) is going to be headed by somebody representing a small country like Hungary, it will show the attitude toward (enlargement) is not serious," Akulenko added.

Budapest hopes to keep Varhelyi in the job, but there is reportedly growing distaste among EU diplomats toward keeping a Hungarian representative in this position ahead of upcoming accession talks with Ukraine.

European leaders agreed last December to launch membership negotiations with Ukraine, and the commission has already put forward a draft proposal for the negotiations framework.

Paul concurred that for successful enlargement, the next commissioner should not be from Hungary but ideally somebody from the Baltic states or elsewhere in Eastern and Central Europe.

The final composition of the commission remains uncertain. According to Politico, the European Council President Ursula von der Leyen remains the front runner for the top seat, even though she faces an uphill battle.

While the support of the parliament's "mainstream trio"—the European People's Party, Renew Europe, and the Socialists and Democrats—should be enough to get von der Leyen beyond the 361-vote threshold, dissent among individual MEPs can lead her to seek support elsewhere.

The current president can still seek support among the conservative ECR—namely Meloni's Brothers of Italy—or the Greens. This means that von der Leyen and the EPP can leave the ID group and other controversial, Ukraine-skeptic parties safely behind the cordon sanitaire.

When asked about the possibility of working with parties on the right, von der Leyen made it clear what positions are unacceptable for her.

"Against (the) rule of law? Impossible. Putin's friends? Impossible," von der Leyen said.

"Are you supporting Ukraine? And are you fighting against Putin's attempt to weaken and divide Europe? And these answers have to be very clear."

Meloni, who made it clear Rome will maintain a pro-NATO and pro-Ukraine course under her leadership despite her right-wing stances on other issues, appears to be a more likely partner for von der Leyen.

"She is clearly pro-European, against Putin, she’s been very clear on that one, and pro-rule of law, if this holds, and then we offer to work together," von der Leyen said of the Italian prime minister.

Akulenko does not see a potential deal between von der Leyen and Meloni as an obstacle for Ukraine, as the latter has even reportedly pressured Orban to back key pro-Ukraine steps.

However, both the EU and Ukraine must use the window of opportunity to push forward with reforms and accession before the far-right's growing momentum gives Ukraine-skeptic populists even more influence in Brussels, Akulenko stressed.