Early look at Ukraine's exhibit at Venice Art Biennale – exploration of world's exhaustion

From an artist’s response to his city’s water mismanagement in 1995 to a work reflecting the world decline in 2022 – the "Fountain of Exhaustion" by Pavlo Makov has come a long way.

Its ultimate destination is the oldest international Venice Art Biennale, where it will represent Ukraine in April. The idea is that the 27-year-old concept will mean much more in times of climate change, which is especially felt in Venice, whose famous canals have been alternating between droughts and floods, the phenomenon known as "acqua alta."

"It’s not that the work has changed – it’s the world that has approached what this work represents," Makov, 63, told the Kyiv Independent.

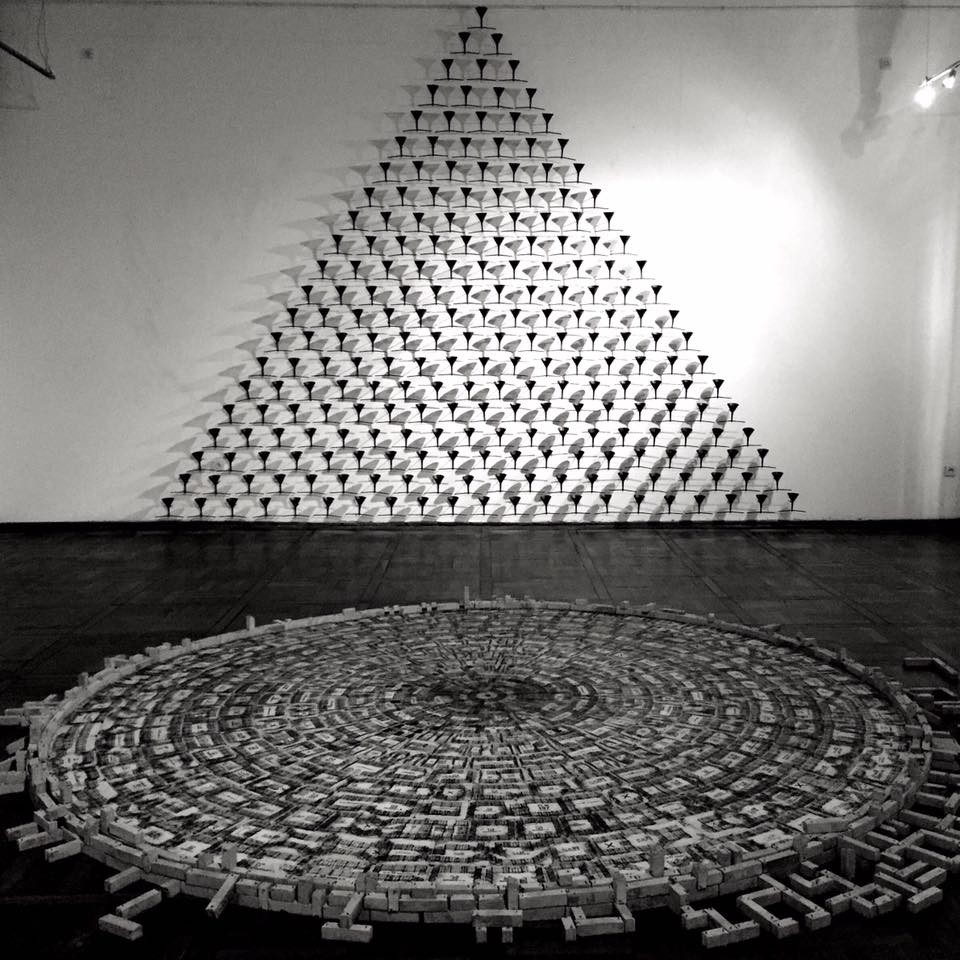

"Fountain of Exhaustion. Acqua Alta" will be a 12-tier pyramid of steel funnels with water flowing into the one on top. Each funnel splits in two, dividing the water between more funnels at each level. By the time it gets to the third tier, the flow slows to a trickle and at the sixth tier, to a drip. At tier 12, it barely seeps through the last 12 funnels, into an awaiting pool.

The display symbolizes exhaustion on many levels, Makov says. Besides the obvious – depletion of humanity’s resources and credit with the environment – it’s about psychological exhaustion due to social media abuse, the pandemic and economic recession.

One could argue that it can also be seen as an appeal for empathy for Ukrainians. For almost eight years, they have been holding off Russia’s proxy militants in eastern Ukraine and now face the possibility of another invasion with over 100,000 Russian troops massed at the borders.

"Makov’s art is political, but not forthright. The work we selected with Pavlo speaks about universal global issues through artistic metaphor and the beauty of the artistic object itself," says Lizaveta Herman, the project’s curator and co-founder of the Naked Room gallery.

Like Ukraine's 10 other projects showcased at the Biennale since 2001, Makov will have the challenge of earning his country its first award at the exhibition inaugurated in 1895. Despite criticism, the Biennale keeps dividing art into national pavilions, although artists of different ethnic backgrounds have been collaborating beyond borders and increasingly in virtual spaces.

But now, more than ever, it's participation that matters most. The project’s three curators see it as a way for the world to reassess the Ukrainian art of the 1990s and its contemporary significance. Especially since the project was never realized as intended – as a fully functioning fountain.

"In our opinion, it’s a great work of art that had remained a rather marginal idea," says Maria Lanko, curator and co-founder of the Naked Room. "It’s our chance to make it visible, to actually realize it."

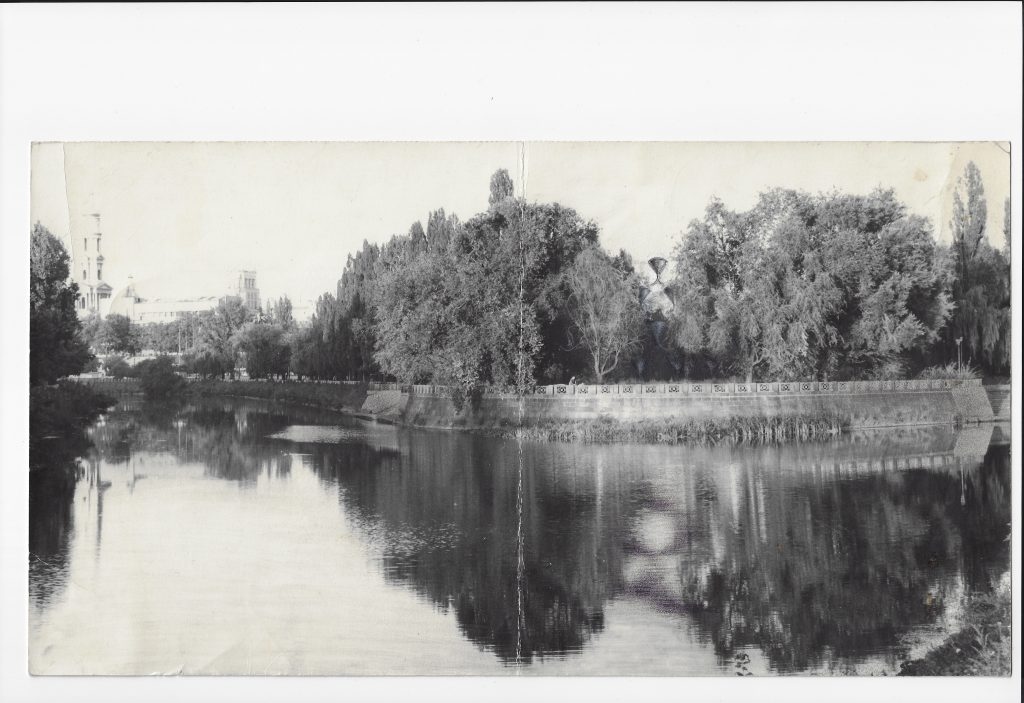

Makov started to develop the idea in drawings and prints in 1995, the year when his city of Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine was going through an ecological disaster. Heavy rain flooded the city’s wastewater treatment plant, spilling polluted water into its rivers and forcing authorities to block tap water supply for six weeks.

At the same time, Makov was examining Kharkiv as the city that lies on three rivers but whose fountains never seemed to work. He saw it as a sign of decline and authorities’ impotence, as opposed to functioning fountains in prosperous communities even centuries ago.

"So the 'Fountain of Exhaustion' emerges as a reaction to this sociopolitical context and as a reflection about this city on the water with fountains that don’t work," the project’s final curator Borys Filonenko says.

In 1996, Makov created the first three-dimensional "Fountain of Exhaustion" – a four-tier pyramid of cardboard funnels on a city wall next to a writing by Oleh Mitasov, a legendary local outsider artist.

And in the next two decades, Makov kept revisiting the idea.

For his "UtopiA" 2003 retrospective exhibition at the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Makov made a seven-tier tinplate version that was bought by the high-paying PinchukArtCentre for a few later displays. And in 2017, Makov presented an imposing five-meter-tall 23-tier version made of brass for the Andrey Sheptytsky National Museum in Lviv.

But much like Kharkiv’s public fountains, none of these models had what the artist intended from the beginning – actual running water.

"This is symptomatic for Ukrainian art, whose history is not only about what happened, but also about what has not happened, has not been properly represented," Lanko says.

The challenge to realize Makov’s vision for the "Fountain of Exhaustion" fell upon the Forma architectural bureau. It’s even more of a puzzle at the Biennale pavilions, where floors have an acute weight limit and nail-mounting is not allowed. And of course, there can’t bе any water supply or drainage.

So the architects have designed a self-contained object that will stand against the wall. After going through all the funnels into the pool, the water will be pushed back to the top by a pump. So in fact, the water won’t be exhausted but actually circulated – invisibly for the viewer.

"There was no other way to do this in Venice," says Makov, who speaks Italian and knows the country well. "The image that everyone sees is what matters."

The Ukrainian pavilion will be located at a busy intersection of the Biennale’s main exposition and other national pavilions, so the architects tried to make it a place of quiet reflection. Besides the fountain, it will include Makov’s drawings, prints and photographs that trace the project’s evolution.

It was selected for funding by Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture after a national competition. Most of the money – Hr 3.5 million ($123,200) paid for the pavilion rent. There is another Hr 4 million ($140,800) more in the budget for things like transportation, installation and opening.

"I’m very happy that it all goes according to the plan," says deputy minister Kateryna Chuyeva, the commissioner of the Ukrainian pavilion.

The Biennale will run from April 23 through Nov. 27 with the title "The Milk of Dreams," a phrase from a series of drawings by Leonora Carrington and a nod to surrealism. Its themes point to issues of environment and human impact: metamorphoses of bodies, the relationship of people and technology, and the connection between bodies and the earth.

Ukraine’s "Fountain of Exhaustion" fits well into this confluence of themes, times and location of the 59th Venice Art Biennale. Contrary to its grim vision, after decades, Makov’s work found new energy and resources to deliver its message globally.

"No, I’m not a pessimist," the artist told the Kyiv Independent. "Let’s say I’m a reasonable optimist."