Dmytro Yefremov: What does an ‘international rules-based order’ mean for China?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.

“China firmly upholds the UN-centered international system, the international order underpinned by international law and … will never accept the so-called rules imposed by the few.”

These are the words of China’s Foreign Ministry’s spokesperson on May 20, commenting on the G7 leaders’ meeting in Hiroshima. The G7 leaders had said in their communiqué that a “growing China that plays by international rules would be of global interest."

The principle of an international “rules-based order” has become a permanent element of China’s official rhetoric and the basis for building relations with other countries. However, Beijing has its own way of interpreting it.

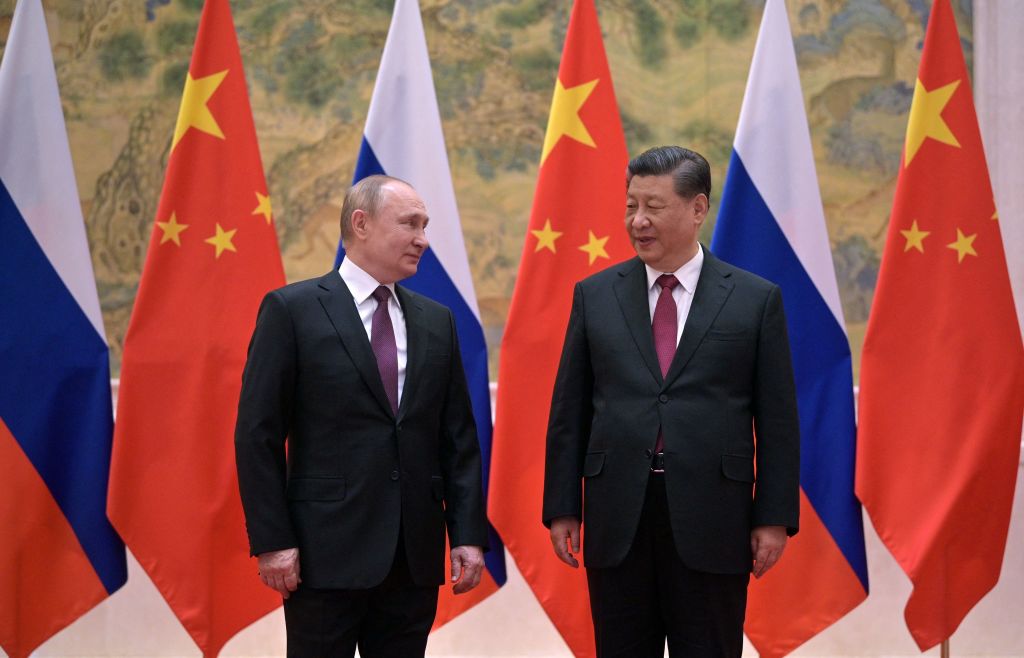

During Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow in March, China and Russia’s joint declaration on “deepening comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation” set out a specific geopolitical goal. The Sino-Russian alternative construct is opposed to a so-called “Western-imposed” rules-based order and differs radically from the Western approach.

Formally, China positions the UN Charter and a number of accompanying treaties as the cornerstone of a world based on international law. Recognizing the principle of legality in international affairs, China has joined or ratified a large number of international agreements – even more than the United States.

At the same time, Beijing is putting forward several new principles that can be described as “adding Chinese wisdom” to international cooperation. This “wisdom” includes a wide range of ideas from the “five principles of peaceful co-existence” (i.e., mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence) to “building a community with a shared future for mankind,” with a train of supporting initiatives by Xi.

Beijing claims that such innovations will contribute to the “democratization” of international relations, strengthening the multipolar model and ensuring the sustainable development of states. Beijing emphasizes the multilateral format of constructing new international norms, through which “developing countries’ voices can be taken into account.”

As a great power, China does not abandon opportunistic behavior in situations where international law is inconvenient to its priorities and interests. It is difficult to recall an agreement with China’s participation in which it would have sacrificed its own benefits in favor of other countries.

In order to prevent its interests from being infringed upon by inconvenient rules of international law, Beijing uses at least six special tactics.

First, China adheres to superficial, non-binding wording in agreements. This is often observed in China’s bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements and World Trade Organization (WTO) reform initiatives – in particular, clauses related to state-owned companies and subsidies.

China’s second tactic is to replace binding norms, especially regarding accountability on topics such as human rights violations, with obligations to engage in discussions. This is also present in China’s engagement with international legislation on cyberspace within the UN framework, where the mechanism of its application is blurred due to overly abstract formulas.

China’s third tactic is to support agreements in which participants can independently determine the level of their commitments.

For example, in the Paris Climate Accords, endorsed by China, participants can set their own emission reduction targets. In the WTO, China defends “special and differential treatment provisions,” where countries decide whether to label themselves as developing states and thus retain the associated benefits. To strengthen its case, China adds normative judgments to its arguments: rich “First World” countries should assume increased obligations compared to countries in the Global South.

China champions a fourth tactic in international agreements: attempting to limit their effect by citing its national security as a priority. In one form or another, sovereignty clauses are present in most of its major economic agreements governing access to its domestic markets and information space.

The most sensitive non-economic example is the 2020 “Law on the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.” It significantly narrowed Hong Kong’s autonomy guaranteed by the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which defined the specifics of Hong Kong’s stay in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) after 1997. The regime lasted 23 years instead of the agreed 50, demonstrating to the Taiwanese government and other nations that, when choosing between compliance with obligations and national security, Mainland China will always choose the latter.

China’s fifth tactic is “denial.” The most sensitive issue for China within the UN framework of international law is that of human rights. Officially recognizing human rights as a “common aspiration of mankind,” Beijing nevertheless asserts that “countries have the right to choose independently their paths of human rights development.” This approach brings it in line with Moscow and other dictatorial regimes.

China invokes the tactic of “denial” when it is not satisfied with various human rights norms, appealing to its own interpretation of the agreements’ provisions, relying on their partial ratification, and selectively implementing them in national legislation. In particularly acute cases, such as regarding the international arbitration tribunal on artificial islands in the South China Sea, China does not shy away from refusing to recognize its decisions.

The sixth tactic, often combined with the tactic of denial, is that of “discourse substitution.” China promotes this tactic most clearly when it tries to replace discourse on universal human rights for the right to development, or the improvement of people’s material well-being at the expense of some human rights.

By promoting development rather than rights, it is easy to ensure continuous "deepening of cooperation,” maintain various dimensions of "strategic partnerships," and guarantee "mutually beneficial" relations with other countries. The question of the equitable distribution of benefits from economic development both among people and between countries is silenced or characterized by general metaphors about "justice," "equality," and "inclusiveness."

China’s 12-point “peace plan” to resolve Russia’s war in Ukraine demonstrates all six tactics. Each point abstains from obliging the parties to take any specific actions, and they are formulated in such a way that each participant can determine which of the points apply to them.

During Xi’s visit to Moscow in March, Putin chose four points from the menu: a call to resume negotiations, preserve nuclear security, end sanctions, and the assertion that current events represent a return to “Cold War mentalities” – and Xi had no objections.

The word “Ukraine” is mentioned three times in the text, and “Russia” twice. Were “Ukraine” and “Russia” to be replaced with any two other countries, the document could equally apply to them. China has stubbornly obfuscated Russia’s responsibility for the war, and the obviously simple way to overcome the war – the withdrawal of Russia’s forces from Ukrainian territory – is omitted.

The plan states that there is “no simple solution to a complex problem” and, instead of fulfilling the obligations stipulated by the UN Charter, it instead pushes for dialogue. The importance of sovereignty touted in the plan’s first point is immediately negated by the second point which says that the “security of a country should not be pursued at the expense of others.”

The human rights to life, liberty, security, and non-discrimination enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights have been reduced in China’s peace plan. China has completely ignored the decision made at the UN General Assembly to condemn Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine and which reflects the international community’s point of view. Instead, the plan includes provisions on strengthening grain exports and ensuring the stability of supply chains, helping “global economic recovery.”

In conclusion, Beijing's approach to a world order based on international law is not just a manifestation of Chinese pragmatism or flexibility. It allows for the formation of an alternative platform and the rallying of those dissatisfied with the American rules-based order, from Iran to Brazil.

Putin defined a rules-based order as one that was "established without our participation." However, Xi's vision is neither nihilistic nor revisionist. His strategy is to relativize the universality of international law to turn it into an obedient tool under China's control.