‘Everyone says culture has nothing to do with it. It does' — Ukrainian writer Volodymyr Rafeyenko on Russia’s war

A man walks past a heavily damaged residential building after a recent air strike on the town of Bakhmut, Donetsk region, Ukraine on Aug. 28, 2022, amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. (Anatolii Stepanov / AFP via Getty Images)

Ukrainian author Volodymyr Rafeyenko never thought he would write a novel in Ukrainian.

He was a native of Donetsk, an eastern Ukrainian city where he grew up speaking Russian and completed a degree in Russian philology. Early on in his career, he was the winner of some of Russia’s most prestigious literary prizes for Russian-language writers.

But then Russia invaded eastern Ukraine over spring and summer 2014. On the train out of the now-occupied Donetsk, Rafeyenko made the decision to switch to Ukrainian, a language he says he could barely communicate in at the time.

“I was thinking about how Russia had illegally annexed Crimea and started the war in Donbas with the false notion of ‘protecting’ the Russian-speaking population. They used us as an excuse to start the war,” Rafeyenko told the Kyiv Independent in an interview, adding that he felt he had to do “something about it.”

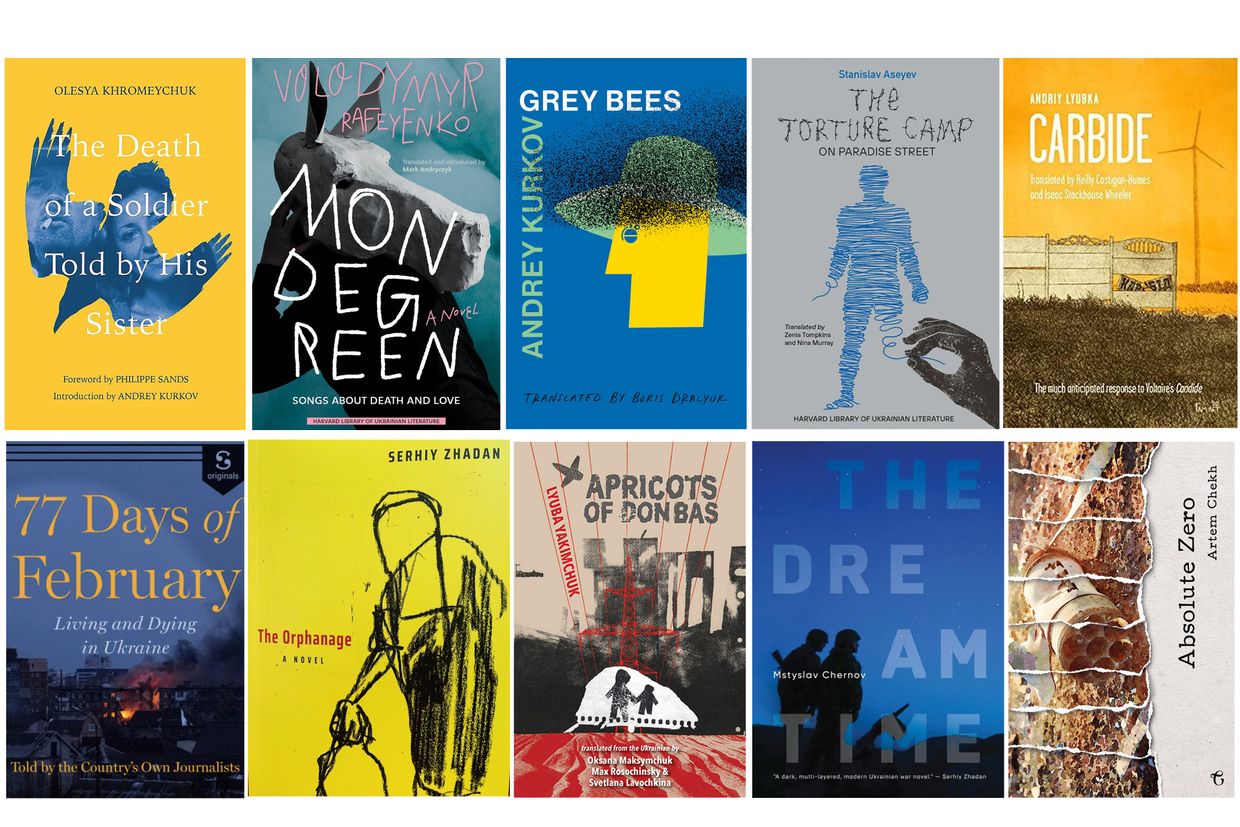

His first novel in Ukrainian, titled “Mondegreen: Songs about Death and Love,” was published in 2019. The English translation was released by Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI) in 2022.

The experimental novel tells the story of a refugee from Ukraine’s Donbas region who flees to Kyiv at the start of Russia’s war in 2014. In Kyiv, he experiences a deep sense of dislocation and alienation as he adapts to his new life and learns Ukrainian.

When Russia invaded his country for the second time in 2022, Rafeyenko and his wife found themselves caught in Russian-occupied territory outside of Kyiv. He wrote a play on the experience published in 2023. The English translation is set to come out next spring.

The Kyiv Independent sat down with Rafeyenko to discuss his life in Donetsk, his journey to the Ukrainian language, and whether or not he blames Russian culture for what is happening.

“Everyone says that culture has nothing to do with it. It does. And (Alexander) Pushkin is to blame.”

This interview has been edited and shortened for clarity.

The Kyiv Independent: Before we delve into discussing the war, could you briefly tell me about your childhood and early literature career in Donetsk?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: I graduated from Donetsk State University, named after (Ukrainian 20th-century poet and Donetsk native Vasyl) Stus, with degrees in Russian language and literature and philology. My education was in Russian. We spoke and wrote exclusively in Russian. Russia was the primary language spoken in the city. Of course, I had friends who were Ukrainian speakers when I was at university. They spoke Ukrainian with each other, at least. But in such a general environment of Russian speakers, they also switched to Russian more often than not. It was difficult to hear “real” Ukrainian being spoken.

Both of my grandmothers were Ukrainian, and Ukrainian was their native language. However, one of my dad's grandmothers used to speak "surzhyk," a blend of Ukrainian and Russian that wasn't purely Russian or literary Ukrainian due to its mixed grammatical and phonetic forms.

On the other hand, my mother's mother had a more complex background. While they were all ultimately Ukrainian, it's worth noting that my grandmother's side, if I remember correctly (I don't have official documents), had some connections to Polish and Jewish heritage. For reasons unknown to me, they left Poland and settled in Ukraine, where they spoke Ukrainian among children, while adults primarily conversed in Polish. It's a bit of a puzzle, but they certainly didn't speak or understand Russian.

My maternal grandmother recounted stories of their life in the village, which I believe was called Shchastia (“Happiness”). When they first attended school, they encountered challenges as the teachers and many classmates spoke Russian, making learning difficult for them.

The Kyiv Independent: What time period are we talking about here?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: It was the early twentieth century. My grandmother set a personal goal for herself to master Russian even better than native speakers. She dedicated herself to this pursuit and successfully completed her studies, eventually becoming an engineer. She worked in a classified design bureau that played a pivotal role in developing the first Soviet lunar rovers. With her specialized education, she was employed in military structures. Naturally, she never conversed with me in Ukrainian — our conversations were exclusively in Russian. However, she often shared stories about her family history and my grandfather's (her husband's) past, which later inspired my novel "Mondegreen."

The historical background of this novel is the story, an absolutely true story, of the life of my grandfather, Oleksii Yehorych. They were rich people, and they were said to have been targeted by the Bolsheviks during the dekulakization period. The parents were executed in front of their children, but miraculously, the children survived. The oldest of the children was not even 10 years old when it happened. They were begging and eventually went to different parts of the world. One of the sisters ended up in the United States, but I don't remember where she is or even her name. This narrative encapsulates the essence of my family's history.

The Kyiv Independent: How did your career as a writer begin?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: I started writing some poetry when I was a child. I think I started writing my first prose when I was in the Soviet Army, something like fairy tales for adults. It was a difficult period for me and I did it in order not to go crazy. I would write fairy tales and read them to my fellow soldiers, or let them read them. And then it so happened that I later became a philologist — reading books and navigating literature became my profession, in addition to trying to write myself. Somehow it all worked out, and I've been writing ever since.

For a while, I wrote just for myself. It was almost impossible to break through and find any opportunities to be published. But I continued to write, and my work sometimes came out in local literary magazines.

Then I wrote a novel and submitted it to the Russian Prize in Moscow. This was a prize for writers who were not Russian citizens but wrote in Russian. My work won second place, and this immediately secured me publication in Moscow's prominent literary magazines. There was some kind of reaction from literary critics to what I was writing, and the attitude (to my writing) changed. A few years later I wrote a novel that won the first place prize. There were roughly forty countries and about five hundred participants.

I was writing in Russian at the time, and I had no idea that someday I would write in Ukrainian. I didn't think about it. I lived, was born in, and grew up in a Russian-speaking region, in a city where, as I said, it was almost impossible to hear Ukrainian. I didn't feel what the problem was then. All this tension of Ukrainian history somehow passed me by, we were not taught it. We were hardly taught Ukrainian at school. There were classes, but none of us could speak it. I learned to read it here and there because my parents had a very large library. My father collected the books himself, and there were, I don't know, several thousand volumes, including Ukrainian books. But I read Ukrainian with pleasure, and when I was at university after the army, I intensively read Ukrainian contemporary authors, starting with (Serhiy) Zhadan, (Yuri) Andrukhovych, and so on. I later began to translate.

I remember that at one point I wanted to make a large anthology of contemporary Ukrainian poetry. I wanted to translate it into Russian and publish a bilingual book so that our Russian-speaking residents, who did not read or understand Ukrainian, could appreciate the level, the great level, of contemporary Ukrainian poetry.

The Kyiv Independent: How were you perceived by Russian audiences? After all, you were different. Or did they not see any difference between a Russian writer and a Ukrainian writer who chose to write in Russian?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: You know, it was a long time ago, but I remember a certain attitude of being perceived as a “little Russian,” not Ukrainian. There was no sense that they were celebrating a Ukrainian writer.

I once had an interview with a decent journalist there who asked me: "Why don't you move here? You write so beautifully. Your texts are published in such cool publishing houses, so why don't you come here?"

I said: "Well, I'm Ukrainian." He didn't understand my reply.

I don’t think he came from a place of malice or that he intended to offend me. It was his sincere feeling, his understanding, and his attitude, which was generally sympathetic. But still, it was tinged with a certain amount of arrogance. I mean, I don't want to offend anyone — there were some very nice people (in Russia), but in general, Russians have a superiority complex, I have to admit.

The Kyiv Independent: I think it’s fair to say that mentality plays a role in today’s events. Speaking of, I’m curious to hear your insight on how the events of 2014 unfolded in Donbas. Why, in your opinion, did this all happen? How?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: I believe that the causes of war primarily stemmed from empire-driven, material, and resource-related factors. In the case of Donbas, our eastern Ukraine, it is a region rich in resources that Russia lacks.

Ukraine also began to undergo a significant shift toward a stronger Ukrainian cultural identity. Despite having a diverse linguistic landscape, with around thirty percent of the population speaking Russian, there was a noticeable move away from Moscow's influence toward a focus on Kyiv. This transition involved dismantling old state myths and adopting new perspectives, which was a powerful and straightforward process. While many of us spoke Russian, it was always a unique blend that included elements of Ukrainian culture. Having grown up in Donetsk as a Russian speaker, I witnessed the emergence of a distinct Ukrainian identity. Our cultural background always remained rooted in Ukrainian traditions, even though we also celebrated holidays with songs in multiple languages.

For example, I remember singing carols, a tradition ingrained in our family and community. During Soviet times, my grandmother would take me out at night to sing carols with other children. This practice was not just about singing; it was about passing down cultural knowledge, understanding the significance of each ritual, and connecting with our heritage. This type of cultural transmission and celebration was not common in Russia.

This shift toward a stronger Ukrainian identity was evident to me as early as the late 1990s and continued into the early 2000s. While some tensions between eastern and western regions existed before the war, the broader trend of embracing Ukrainian culture was palpable.

Some of us speak more Russian, while others lean toward Ukrainian. But we are all Ukrainians. The steppes have always been inherently Ukrainian, marking the boundary between Greco-Roman and Mongolian civilizations, running through Donetsk and between it and Mariupol. It was here that we stood, negotiating and facilitating communication between these two worlds, living on the border as our challenge and destiny. This is how our civilization, the Ukrainian steppe civilization, came to be.

While I won't delve deeply into historical details here, it's important to note the sentiments and realizations of the people. They recognized that Ukraine was coalescing around Kyiv, both in terms of the elites and the general populace, and there was a significant inclination toward Europe and the West. However, this was not universally welcomed, particularly by those who benefited from Ukraine's historical ties as an extension of the Russian market and economy. I'm aware of the presence of Russian business in Ukraine during that time, but I won't elaborate further on that aspect.

The Kyiv Independent: How far back are there signs pointing to all this?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: The reality is that signs of what was to come had been present for quite some time, stretching back to the early 2000s. They were preparing everything at least 10 years in advance, I believe, if not more.

I remember how in the early 2000s Russian military personnel and pensioners began to relocate and settle in our region. This migration wasn't sporadic. What struck me was how swiftly many of them secured influential roles within the police, SBU, security agencies, and public administrations. It seemed orchestrated, not random. Admittedly, I'm not a secret- service officer or military official, but I couldn't ignore the clear pattern unfolding before me. It felt like a deliberate effort by certain forces to bolster their presence within Ukrainian institutions, setting the stage for future events.

During this time, we witnessed the emergence of pro-Russian sentiments, particularly in the form of a political party in Donetsk advocating for the so-called "Russian world." This movement sought to undermine Ukrainian identity, culture, and language in all spheres of public life. Our local security services remained passive, allowing these sentiments to gain traction unchecked.

So don't think that 2014 suddenly dropped this on their heads. No way! They had been preparing for ten years, if not more, since the early 2000s for sure. And their agents of influence worked in Donetsk as well.

The Kyiv Independent: Could you describe what it was like to be in Donetsk in 2014? What did you witness there firsthand?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: We lived right in the heart of the city, in a spacious apartment. It was as central as you can get, just a hundred meters from the Opera and Ballet Theater. I was a bell ringer at the central cathedral. On a weekend, perhaps a Sunday—the sixth of July, if I’m not mistaken—we were tasked with calling for the Second Liturgy between eight and nine o'clock in the morning.

As the clock approached nine, we ascended the bell tower. On that particular day, as I peered out, I witnessed the city center being overtaken. Armed individuals, carrying machine guns, marched toward the university dormitories. Their movements were coordinated, with logistics clearly prearranged. They operated like a well-oiled machine, calmly occupying key intersections and directing columns in different directions.

I had a hope, a dream, that the Ukrainian government would not give up Donetsk and do something similar to what they did in Kharkiv, where they called in special forces to solve the problem. For some reason that didn’t happen in Donetsk, though, and I still don’t understand why.

Less than a week later I already left for Kyiv. I didn't have any connections in the capital—no friends, no acquaintances, just a few superficially familiar faces. Thankfully, one of them graciously offered to let me stay in his place while he was away, giving me a two-week window to settle in and explore the city. That’s how it all began…

The Kyiv Independent: And that’s when you switched to Ukrainian? Why did you make that switch?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: My decision to switch to the Ukrainian language happened on the Donetsk-Kyiv train on July 12, when I fled my home. I was thinking about how Russia had illegally annexed Crimea and started the war in Donbas with the false notion of “protecting” the Russian-speaking population. They used us as an excuse to start the war. So, something had to be done about it.

This was an obvious falsehood for the locals, other Ukrainians, and even Russians themselves. However, this narrative was perceived differently — sometimes even as truth — in parts of Europe and in the United States, and elsewhere. Something had to be done about it. What could I, a person who was indirectly linked to the cause of the war, do? I resolved to master the Ukrainian language at a proficient enough level that would enable me to write fiction.

My journey with Ukrainian began in 2014 from scratch. Upon arriving in Kyiv, I couldn't even converse with a store clerk in Ukrainian or express simple ideas properly. Now, in 2018, my English surpasses the level of Ukrainian I had in 2014. Despite setbacks, I persevered and eventually published my first Ukrainian novel after five years of effort.

In 2019, my novel “Mondegreen” was officially published in Ukrainian. Interestingly, it had been translated into English and published by Harvard University’s Institute for Ukrainian Studies a month before the war's escalation in 2022.

The Kyiv Independent: Why did you decide that was the first story you’d tell in Ukrainian?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: The main character of this book is the Ukrainian language, which also happens to be the pivotal element of my life. My journey with the language, from learning it to eventually being able to write books in it, marks a significant milestone. This novel encapsulates a delicate sense of freedom, tinged with vulnerability, experienced by an immigrant who has lost everything.

Every aspect of my life that I cherished — homes, childhood memories, friendships, familiar streets — was stripped away due to circumstances imposed by the Russians and the war. In exchange, I found solace and purpose in the Ukrainian language. I deemed this linguistic acquisition as a meaningful substitute. It brought me a unique form of happiness, which in turn gave birth to this novel.

The Kyiv Independent: What was it like to be a refugee in your own country?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: Hard. Back then, a person from Donbas was looked down upon in central Ukraine, not to mention western Ukraine. There were job or apartment listings that excluded people from Donbas. It was difficult to find work or housing. The prevailing attitude was that we were to blame for the Russians occupying Donbas.

I won’t name names, but there were some prominent western Ukrainian figures who broadcast this twisted idea that we should just “give up” Donbas. Not everyone thought like that, of course. There were normal Ukrainian-speaking, cultured people who helped us later on.

But it was hard… I was a Russian philologist by profession that found itself at war with Russia. I’d come to a strange city, to the capital, without our friends, without any other specialty, and I needed to feed myself, to manage, to feed my family somehow. My parents stayed behind in Donetsk and they also needed help. Beforehand, I’d been published mainly in Moscow. People there knew my work. But in my native country, people didn’t know my work and oftentimes seemed like they didn’t want to know it, simply because I was a Russian speaker. It was against this backdrop that I learned to write in Ukrainian. Despite the difficulty, this period in my life had its fun moments.

The Kyiv Independent: Where were you when the full-scale invasion started?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: We were in a house about an hour away by bus from Kyiv. It was situated between Bucha and Borodianka and intersected with the central Warsaw and Zhytomyr highways. These highways became routes for heavy Russian military equipment during the attack on Kyiv. On Feb. 24, while in our house, my wife woke me up to news about the war. Initially, I didn't grasp the seriousness of her words. After a brief pause, I did some exercises, had coffee, and went online. That's when I realized the gravity of the situation as missile attacks commenced.

I began contemplating how to relocate my wife to western Ukraine, but the reality was grim. Tank battles and intense fighting near Kyiv made any escape route impossible. Even with substantial financial offers, I couldn't find anyone willing to transport my wife to Lviv or Poland due to the presence of Russian military units and sporadic Belarusian forces along those roads.

The fear among people was palpable, making any movement toward safety challenging.

Soon enough we found ourselves in a dire situation. We lost access to power, water, internet, and mobile communication within days. The incessant sound of gunfire became constant, shaking our two-story summer house which lacked a basement for shelter. The doors swung open and shut on the sound vibrations. I feared the house might collapse on us, but miraculously it held steady.

The continuous gunfire, day and night, accompanied by explosions, kept us on edge. I discovered missile fragments just seventy centimeters from our doorstep, dangerously close to vital infrastructure. The area was surrounded by Russian forces occupying nearby villages, engaging in heavy combat with our own forces. The chaos of battle raged around us.

Our particular location wasn’t of strategic importance to the enemy and I think that’s why we ultimately survived. You couldn’t even find our location on a map.

In a few days, the people with pet dogs who roamed the forest discovered a brief window of five to seven minutes in the morning or evening where they could catch a mobile phone signal and have a short conversation. A small dash on the phone signaled the reception of a signal from a mobile tower. This phenomenon occurred due to specific meteorological conditions that directed the wave to certain clearings in the forest. Each day, there was a chance to catch this signal that could last anywhere from a minute to five minutes before disappearing.

It provided enough time to make a call, exchange information, or receive updates. These clearings became gathering spots for dozens or even hundreds of people who would all try to communicate simultaneously. During this time, my main focus was on contacting Kyiv and my friend, fellow author Lyubko Deresh, who eventually connected us with volunteers who facilitated our evacuation.

This experience later inspired me to write a play.

The Kyiv Independent: Did you write that play while you were living under occupation or after?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: After we were evacuated. I thought I would write a novel first, then a play. We were in Ternopil, and my wife was invited to go to her friends in the Czech Republic. In my solitude, I somehow didn’t have time for a novel. I felt compelled to start writing the play first. It was nearly impossible to write during the occupation because I typically work on a computer and there was no electricity. I kept a diary during that time, though. I wrote it on paper. The diary is still with me, and someday, I’ll write something based on its contents. But something creative? It was impossible during that period. I was in such a difficult psychological state. Artistic creativity requires some sense of security or at least the possibility of having a rest.

The Kyiv Independent: I’m interested in your thoughts on how this war might end and how occupied territories can be reintegrated into Ukraine.

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: It's certainly a challenging situation. I wouldn't advise rushing into anything just yet, considering the uncertainty surrounding the duration of this war. We're unsure if there will be anything left to integrate in the future. Take Mariupol, for example — it's practically gone. Kherson is still standing, but it's under constant attack.

As for Donetsk, the city is all about mine workings. It was forbidden to build in the city center, because there is a big void there, very close to these mines. There are kilometers of empty space under the city center. If they drop a few bombs like they did in Mariupol, Donetsk will not be easy to rebuild. There will be these pits, these abysses. The water situation is terrible there. They stopped pumping water out of the mine workings, and it started to flow into the drinking water supply. The black soil in that region used to be incredibly fertile and powerful for agriculture. The agricultural sector has historically been robust there. However, now it's depleted and destroyed, lacking sufficient water. Additionally, there used to be a strong metallurgical industry with enterprises in Donetsk, but they've been dismantled, relocated to Russia, and ultimately ruined. I'm uncertain about what the future holds for that area and how things will unfold.

Reintegrating the population will be part of an even greater, looming problem. But the most loyal pro-Russian collaborators there will leave, and there will be a large remainder of the population that is neither yours nor ours, so to speak... They will not care who is in power so as long as they are not being shot at. Give them bread, a peaceful sky, and the opportunity to live somehow. They might not love Ukraine, understand the Ukrainian national idea, or even speak Ukrainian. However, they will still be a population that requires power, order, and education. This transition will not happen quickly, given the deep wounds inflicted on Ukraine by the Russian Federation.

In the last decade, around a hundred thousand children were likely born there and raised in these kindergartens where they were taught to idolize Russia and denigrate Ukraine. What became of these children? They are not at fault for what happened — we must find a way to coexist with them. You have to tell them stories, show them movies, and so on. It will take a lot of work.

I believe that ideally, although I'm unsure of how this would be implemented, if nuclear weapons are not used and these cities remain, even in a symbolic manner, it would be beneficial for some European countries to take responsibility for this region. This would involve English, American, and French educators alongside Ukrainian teachers, as well as humanitarian missions and other support. Additionally, foreign investors could take control of seventy-five percent of the industry for a period of time to help improve the situation. This region would become special in its own right—a zone of international responsibility. Politically, it would remain Ukrainian, but significant actions need to be taken there.

The Kyiv Independent: Do you have any hope that someday Russia will change?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: The only viable solution would be to divide it into thirty or forty different states. Any other approach is not feasible. The current geographical and political setup poses a significant problem for the entire world. Ukraine regaining its territories according to its 1991 borders doesn't guarantee anything. In fact, I believe it might incentivize the Russian population to rally around certain ideas which would be a step backward, essentially reinforcing their beliefs and making them more resolute. We all recognize this reality — it's incurable. Russia is like a disease that requires radical treatment. The current form of Russia cannot continue to exist — it's unsustainable. The international community must take decisive action in terms of security and governance. External oversight of these state entities will likely be necessary for the next few decades if not a hundred years. Russia is not capable of achieving anything positive on its own.

If we fail to address these issues and only settle for restoring pre-existing borders and signing peace agreements, the situation will deteriorate within five to ten years. At that point, there's a real risk of resorting to nuclear weapons because they believe there are no other alternatives. And they are capable of this. They are.

The Kyiv Independent: Should we and can we blame Russian culture and the Russian language for what is happening in Ukraine?

Volodymyr Rafeyenko: I believe that what's occurring is deeply rooted in the Russian language, culture, and literature—a sort of matrix that reveals itself over time. The imperial consciousness in Russia is the belief held by people that, by mere birthright, they possess the authority to control the destinies of other peoples and nations. They feel entitled to dictate what should or should not exist or thrive. This aspect should not be underestimated or ignored.

Of course, there are no inherently bad languages. But when discussing culture, we shouldn't merely regard an object as something worthy of veneration. Instead, we must view culture in a broader context. Culture is a multifaceted entity with a distinct purpose, and it's essential to assess each culture by recognizing whether it fulfills its primary function. What is this function? The culture of every nation, and every person, serves to guide and shape human behavior within that group; certain actions become possible or impossible due to cultural influences. When culture fails to fulfill its role in cultivating a nation or its people, then there's an issue with that culture, not to mention the people affected by it.

I am still a specialist in Russian literature, or at least I used to be. It's been ages since I last delivered these lectures, and I have no intention of doing so again. All the same, I’m well-versed in the golden age of Russian literature, which undoubtedly began with (Ukrainian author who wrote in Russian Nikolai) Gogol.

Throughout this era of Russian literature, there's a prevalent theme of arrogance and a dismissive attitude toward other nations, evident on nearly every page, starting from Pushkin. There's a pervasive disdain for Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, and anyone else in close proximity. For instance, in Lermontov's "The Lullaby," there's a line that reads, "The evil Chechen is crawling to the shore."

We see how Russia behaves toward Ukraine now. It once seemed unthinkable in the twenty-first century. Destruction of humanitarian infrastructure of museums and libraries. They burn books, destroy books. They rape children in front of their parents and parents in front of their children. It is fundamentally incompatible with humanity and everything we stand for. When people point to figures like Tchaikovsky and Pushkin, I acknowledge their contributions to European culture, to some extent. But I argue that Russian culture no longer exists. It was a conceptual framework, and culture itself is a fluid concept.

We often discuss the challenges of defining culture in tangible terms—it's like trying to grasp a conscience, something simultaneously imaginary yet undeniably concrete in its impact on society. The presence or absence of a vibrant culture is evident in how individuals and nations conduct themselves, whether they uphold values in their actions, politics, and self-organization. This, in turn, reflects the quality of the culture they have fostered. We can see the true quality of a culture by observing behavior and decision-making. That's it. Everyone says that culture has nothing to do with it. It does. And Pushkin is to blame.

Volodymyr Rafeyenko’s novel “Mondegreen: Songs about Death and Love,” translated into English by Mark Andryczyk, is available for purchase online from major retailers.