She survived occupation. Now she hopes her partner survives captivity

Anastasiia Buhera, a university student from Izium, hid inside her sofa when she heard the Russian soldiers approaching. She held her breath and froze in fear.

On that day in May, ten Russian soldiers searched every room in Buhera and her parents’ home in then-occupied Izium, Kharkiv Oblast. As the soldiers questioned her family members, 21-year-old Buhera lay hidden in a cavity inside her sofa, slowly running out of oxygen.

She had heard stories of Russian troops raping and torturing women in occupied parts of Ukraine and knew that her life would be in danger should she be found.

As she lay in the darkness, Buhera clutched a doll – a present from her boyfriend. During that petrifying moment, she thought of him.

“I imagined him hugging me, saying: ‘Don’t be afraid, I’m with you. Everything will be fine,’” Buhera said.

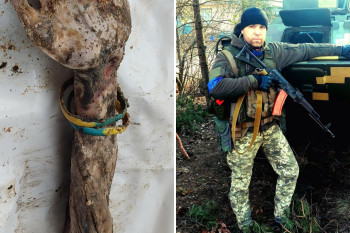

Her boyfriend, 23-year-old Ukrainian serviceman Kostiantyn Ivanov, was already in Russian captivity. He had helped defend Mariupol before the city was fully occupied.

Buhera believes he was captured by Russian forces at the Azovstal steel plant, Ukrainian forces’ last stronghold in Mariupol, and sent to a prison in Russian-occupied Olenivka, Donetsk Oblast. In late July, over 50 Ukrainian prisoners of war were killed in what is believed to be a Russian attack on a prisoner camp in Olenivka.

Buhera still does not know her boyfriend’s whereabouts.

During their search that day, the Russian soldiers did not discover Buhera’s hiding spot, and she eventually escaped Izium amid constant shelling in July.

Two months later, Ukraine launched a surprise counteroffensive in Kharkiv Oblast, liberating Izium and over 500 settlements as of Oct. 14.

While Buhera is safe and living in Poland with her boyfriend’s mother, her struggle to find her boyfriend continues.

“He said he would come back to me,” Buhera said. “I believe he will.”

‘Happy birthday, sunshine’

Buhera, who studies law at the National Aerospace University, was based in Kharkiv before Russia’s full-scale invasion. She happened to be in her hometown of Izium when the war broke out and, like thousands of Ukrainians, woke up on Feb. 24 to the sound of explosions.

Her boyfriend had called her that morning, urging her to move away from the front line to western Ukraine. Buhera refused, saying she could not leave without her parents who, in turn, refused to flee without theirs.

“Our reluctance to leave each other left us all in Izium,” she said.

Buhera and her mother, alongside many in Izium, contributed to Ukraine’s fight by preparing meals for local volunteer defense units. She said that, despite shortages across the city, people continued to donate food for their defenders.

Russian forces started to shell Izium heavily on Feb. 28, Buhera’s birthday. She said they targeted supermarkets and residential buildings that night. Since then, she said Russian forces have bombarded the city almost non-stop.

The day she turned 21 was also the last day they had electricity.

Her family had been watching the news, drinking the juice her father had brought home – something so ordinary during peacetime and so rare during the war with grocery stores either closed, destroyed, or out of stock.

“My dad raised a glass of juice and said, ‘Happy birthday, sunshine!,’” she said. “I started crying.”

“I was upset that, because of some crazy people, I had to celebrate my birthday like this, spend my youth like this, not knowing whether I would even wake up the next morning,” Buhera said.

Five months of horror

Soon after Ukrainian forces liberated Izium on Sept. 10, a mass burial site containing 447 bodies was discovered on the outskirts of the city.

Kharkiv Oblast Governor Oleh Syniehubov said that some of the bodies exhumed from the graves displayed signs of torture and violence. Only 21 of the exhumed bodies were soldiers – the rest were civilians, including children.

While she did not witness the murders committed by Russian troops in Izium, Buhera said she has heard of many of their atrocities.

According to her, Russian forces shelled civilians queueing for food during the first weeks of the invasion. She also said an entire family was killed by a Russian bomb as they were trying to take shelter underground, leaving only a four-year-old child.

“It was pure horror,” she said.

“They had to collect their remains all over the yard because they were torn to pieces.”

When Russian soldiers fully occupied Izium in April, Buhera said they searched for residents with links to Ukraine’s military. According to her, Russian troops detained men, torturing them with electric cables.

“One man returned (home) in terrible condition. He was all beaten up and couldn’t walk for the first few days,” she said.

After Ukraine liberated Russian-occupied parts of Kharkiv Oblast during its counteroffensive, 22 torture chambers were discovered. Detention centers had been set up in nearly every settlement occupied by Russian forces, torturing detainees with electric shock, beatings, suffocation, and rape.

Buhera recounted how Russian troops would drunkenly loot Ukrainian homes or shoot down birds at local farms for fun.

The day that Russian soldiers forcibly entered her parents’ home was one of the most frightening moments of her life. Her father had set up the hiding spot for her in the sofa in advance, she said. When the Russian soldiers entered her yard, Buhera’s grandparents covered the hiding spot with a blanket and sat on the sofa.

“It was horrifying,” she said. “I prayed that they wouldn’t uncover the sofa.”

Ukrainian student Anastasiia Buhera spent five months in the Russian-occupied city of Izium, Kharkiv Oblast. According to her, Russian troops have been shelling and bombarding the city almost non-stop. Ukraine launched a surprise counteroffensive in Kharkiv Oblast, eventually liberating over 500 settlements, including Izium, as of Oct. 14. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Buhera’s parents told the Russian troops that they did have a daughter, but that she was in Kharkiv. When the troops left, Buhera remained near the sofa in case they returned.

Amid the horrors and constant bombardment in Izium, Buhera continued to think of her boyfriend and what he had to endure defending Azovstal.

He promised

Buhera met her boyfriend at her university’s military training department in Kharkiv.

She said she did not like him at first, but she soon realized they had a lot in common. “His dreams were similar to mine,” she said.

He is a true patriot of Ukraine, she said, adding that he had wanted to join the military for a long time. He eventually did in November.

When Russia started its all-out war against Ukraine, her boyfriend had already been stationed in Mariupol for military training.

She said the last time they spoke on the phone was March 3 – a brief conversation due to a poor connection.

“He said they were fine, holding on,” Buhera recalled. “Everything was always fine, according to him.”

Several weeks later, Buhera’s boyfriend had sent her videos from Azovstal, where around 2,000 Ukrainian soldiers and civilians, including children, were trapped during Russia’s siege of Mariupol.

In the videos he sent her, Buhera’s boyfriend told her that there was very little food left. She said she could tell that he was starving, saying he looked like a “completely different person.”

“He was exhausted,” she said. “It was clear that he did not eat or sleep well.”

The last time his loved ones heard from him was on April 24, when he called his mother.

As per the UN- and Red Cross-mediated deal between Ukraine and Russia, the defenders of Azovstal were relocated to Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine in May. Of the Ukrainian soldiers captured, 211 were transferred to occupied Olenivka.

It was soon confirmed by relevant parties that Buhera’s boyfriend was among the Azovstal defenders relocated to Olenivka. Buhera said she later saw a man resembling her boyfriend in some of Russia’s propaganda videos featuring the prisoner-of-war camp.

Her boyfriend’s name was not on the list published by Russia of those killed in the attack on Olenivka in July.

“But it was a list made by Russia, and Ukraine did not confirm it,” she said.

Buhera and her boyfriend’s mother reached out to the Red Cross in late August to try to locate him, but the organization did not respond.

She said she hardly slept on Sept. 22, the night that Ukraine brought back 215 prisoners of war, including Azovstal defenders, from Russian captivity. She had hoped to see her boyfriend’s face among those released.

While his face did not appear, Buhera still has hope.

“He promised he would come back,” she said. “He has no choice but to keep his word.”

And she has no choice but to continue her search.

“He was fighting for us. Now it’s our turn to fight for him.”