Our readers' questions about the war, answered. Vol. 10

Artillerymen of Ukraine’s 152nd Separate Jaeger Brigade operate in combat positions as artillery units fire toward Russian positions in the Pokrovsk district of Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine, on Jan. 1, 2026. (Marharyta Fal / Frontliner / Getty Images)

Editor's note: We asked members of the Kyiv Independent community to share the questions they have about the war. Here's what they asked and how we answered.

Join our community to ask a question in the next round.

Question: Why has the Ukrainian government chosen not to lower the conscription age to 18 despite the country’s manpower shortages and ongoing security threats from Russia?

Answer: This is indeed a complicated topic, with both sides having valid arguments for why they believe it should or shouldn't be lowered.

The Ukrainian government is against lowering the conscription age to 18 due to demographic concerns. Ukraine's 18-25 age group is the smallest segment of the working-age population in the country, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported, citing United Nations' data. Further lowering the conscription age after bringing it down from 27 to 25 in 2024 could leave post-war Ukraine with an even worse demographic gap, especially with the current rate of casualties that the Ukrainian military endures on the front.

I think another reason is because politicians are afraid to push for such a move, since their rating could suffer. Top Ukrainian officials, including President Volodymyr Zelensky, rarely bring up mobilization, which political analysts suspect is a move not to be linked to a very unpopular topic.

We've also covered the topic here. — Asami Terajima, reporter

Question: How does the Ukrainian public view Donald Trump, particularly in terms of his motivations and political loyalties?

Answer: Donald Trump's policy on Ukraine has led to disillusionment among the Ukrainian public. It has become increasingly clear that the U.S. president does not care how the war is resolved, as long as he can declare himself the peacemaker and add another notch to his "conflicts ended" list.

Ukrainians have taken note that Trump and some members of his team have been receptive to Russian arguments, be they about Ukraine's NATO aspirations, Russian claims on Ukrainian territories, or who is actually to blame for the war — a question that is not really up for debate in Ukraine.

Only 21% of Ukrainians trust the U.S. This is about half the figure from a year ago, before Trump took office.

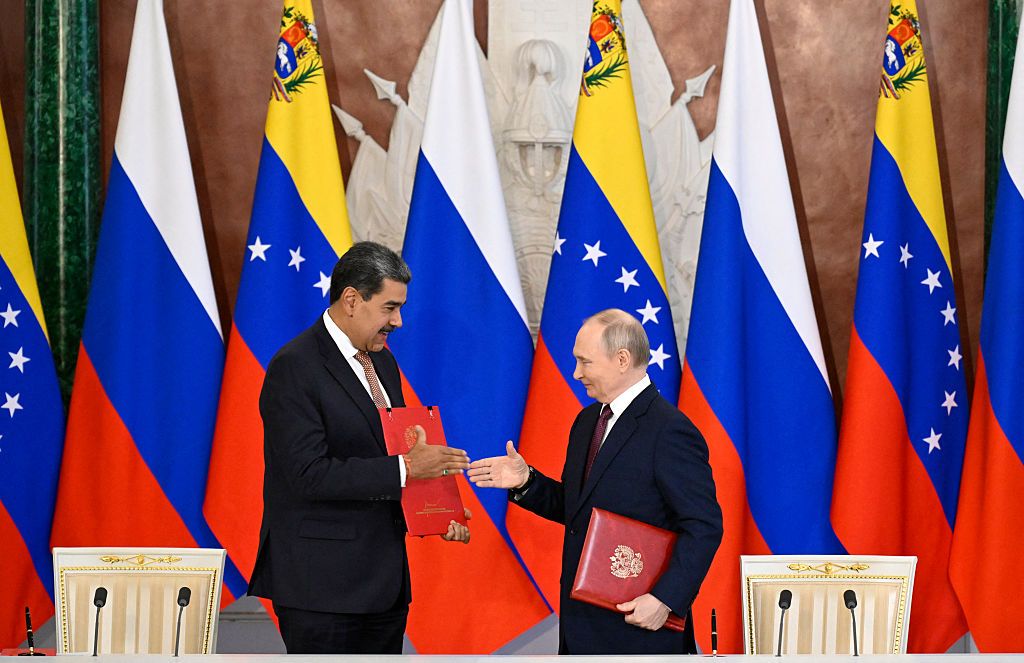

Trump's sympathies for dictators and authoritarian leaders like Putin are also nothing new.

There have been "bright spots" in the last year, of course, for example, when Trump imposed sanctions on Russian oil giants or when he "appeared" in favor of sending Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine. But these sudden and fleeting turnarounds only reinforced the perception that under Trump, the U.S. is an unpredictable and unreliable partner at best, and that Trump himself holds no strong convictions or loyalties, except to himself.

As evidence, an opinion poll from December shows that only 21% of Ukrainians trust the U.S. This is about half the figure from a year ago, before Trump took office. — Martin Fornusek, senior news editor

Question: What specific concerns do Ukrainians have about potential territorial concessions in peace negotiations, and how does public opinion shape Ukraine’s approach to talks with Russia?

Answer: The main concerns Ukrainians have about potential territorial concessions is the fact of losing territories and the Ukrainian people living on them.

Seventy-four percent of Ukrainians oppose a peace plan that would include Ukraine's withdrawal from the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and a cap on the army's size without reliable security guarantees, according to results from a poll released by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology on Jan. 2.

The fact that the majority of Ukrainians are against losing this war and are ready to continue fighting off Russia shapes President Volodymyr Zelensky’s approach to peace talks. He knows that he wouldn’t be able to sign an agreement that is not supported by the population. — Oleksiy Sorokin, deputy chief editor

Question: What is the current level of public support for President Zelensky among Ukrainians?

Answer: The latest poll showed that 61% of Ukrainians trust President Volodymyr Zelensky as of mid-December. Some 32% do not trust the president. Despite the biggest corruption scandal of Zelensky’s presidency, which involved his allies, the number of those who trust him has actually seen a slight increase since October.

However, the scandal initially caused a drop in trust, falling by around 10%, according to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology.

The rebound in trust was influenced by two factors. First, Zelensky dismissed the head of the President’s Office Andriy Yermak — a politically significant step that many Ukrainians had long been calling for. Second, the U.S. increased its pressure on Ukraine for a peace plan that didn’t safeguard the country's interests, effectively pushing it toward capitulation.

Any pressure from the Trump administration on Zelensky is perceived as pressure on Ukraine itself, prompting people to rally around the president. Usually, events like the White House clash boost Zelensky’s domestic support, even if temporarily. — Kateryna Denisova, politics reporter

Question: How many officials have been charged for corruption so far, and what are the specific charges? Are related corruption cases expected to emerge, and could additional officials be implicated? What is the current status of Yermak, including his claim of going to the front, and are there efforts to recover embezzled funds?

Answer: If the question is in regards to all corruption cases: From 2016 to 2024, 63 members of parliament, 46 officials of national government bodies, and 86 judges were charged by the SAPO and NABU.

From the court's creation in 2019 until June 2025, the High Anti-Corruption Court has convicted a total of 258 people.

These include 10 members of parliament and cabinet officials, 13 regional lawmakers, 23 judges, five prosecutors, 27 state company executives, and 20 lawyers.

If the question is in regards to the Energoatom scandal: Eight suspects have been charged in the Energoatom case with bribery, embezzlement, and illicit enrichment.

Former President’s Office Head Andriy Yermak, Justice Minister Herman Halushchenko, and Energy Minister Svitlana Hrynchuk are under investigation but have not been charged yet. They might be charged in the future.

The status of Yermak and his whereabouts are unclear. The Ground Forces of Ukraine said recently that he is not serving there. — Oleg Sukhov, reporter

Question: What would happen if the U.S. withdrew military — and more importantly — intelligence aid to Ukraine? I'm guessing Europe and other allies can't plug that gap.

Answer: The short answer is that there won't be an immediate catastrophe, but things will get harder, it's just hard to measure how much. I will not pretend to know the fine details, because the exact nature of the support at this point in time is secret for a very good reason.

Most likely, we are talking about satellite images for mid- and longer range strikes on juicy targets behind the front line, such as those sitting on airfields in occupied Crimea or inside Russian territory. It's hard to quantify that effect, because on the front line itself, tactical reconnaissance and striking is done with Ukraine's own layered system of quadcopter and fixed-wing drones, and that is the most important part of what is stopping Russian advances on a day-to-day basis. — Francis Farrell, reporter

Question: Is the actual population of Ukraine lower than the official current estimates? Do we know how many people have left Ukraine?

Answer: It depends who is conducting the “official” estimate. But looking at the range of estimates from UN to IMF, Ukraine’s population is somewhere between 30-37 million. It's constantly in flux as Ukrainians come and go, so it's hard to get a truly accurate figure. The UN says there's some 6 million Ukrainian refugees abroad, but we don't know what that means for the country's population. There hasn't been a census for around 25 years. Regardless, it's well below the pre-war 41 million figure.

The question is, what will it be post-war? If the travel ban for men is lifted, will we see people returning to reunite with their families or will we see men moving abroad?

The government is already mapping out routes to attract people back, while businesses are pushing Kyiv to make it easier for foreign workers to come in.

Ukraine’s demographic crisis, which was already bad pre-war, will be its biggest post-war threat as it will need both the manpower and the taxpayers to rebuild. — Dominic Culverwell, business reporter

Question: Will the decision to let 18-22 year olds allow going abroad be changed? What was the argument for this new law in the first place?

Answer: Despite a pretty negative reaction from Ukrainian society, there doesn't seem to be any sign that the travel ban will be reinstated for 18-22-year-old men. The government likely realizes it was a mistake, but going back on the decision would make them look inconsistent.

The argument was that it will encourage those young male Ukrainians living or studying abroad to travel back to the country without fear of being unable to leave again. But it seemed more like an ill thought out populist plan to score some wins among frustrated young men.

I was talking to my irritated barber recently, and he told me that he's lost 50 clients since the ban was lifted, so it's probably done more damage than good for the government’s reputation. And, as I recently wrote about, employers are seeing waves of resignations as young men opt to leave the country. — Dominic Culverwell, business reporter

Question: Has Ukraine received anything in return for signing over the precious minerals to Trump?

Answer: I don’t see the minerals deal being a thing anymore. The ongoing political cycle is as follows: The U.S. pressures Ukraine to sign a bad deal, Kyiv spends time and resources, often months, to renegotiate and make the deal slightly less bad, the U.S. appears to agree, and then suddenly loses interest. The cycle repeats itself every 2-3 months.

Ukraine is now negotiating three to five new deals with the U.S. Among them is a "prosperity and reconstruction package.” The package would see large-scale investment into Ukraine following the end of the war. That’s the new big thing. — Oleksiy Sorokin, deputy chief editor

Question: Is there a realistic scenario in which Russia experiences an economic crisis so severe it critically damages its war-waging capabilities, or is this scenario more of a hypothetical?

Answer: The first thing to look out for is how fast Russia spends the liquid part of its National Wealth Fund. The amount of usable funds has shrunk from around $120 billion in 2022 to roughly $50 billion in late 2025. This means that in 2027, Russia will most likely run out of a pile of cash that helped it plug the holes in its budget. The second thing to look out for are the oil prices and sanctions against India. The lower the prices, the less money Russia will be getting. And if India is bullied into turning away from cheap Russian oil, Moscow may have a problem.

But, the answer to your question is actually — no. If the Russian government runs out of money to finance the war, this would simply mean that they would cut non-military expenses, social security, healthcare, education and more. Russian President Vladimir Putin sees the war against Ukraine as his most important endeavor, if Russian people would be forced to eat less for him to achieve his goals, Putin will take that option. — Oleksiy Sorokin, deputy chief editor

Question: The picture now is somewhat confusing. Russia is grinding slowly forward while losing people and equipment. Ukraine attacks in the rear, at long distances against supply chains, factories, and the energy sector. But what is the status? Have these attacks started to have any effect on Russia’s offensives?

Answer: What is going on is, broadly speaking, the same brutal war of attrition that we have seen over the past year, but with a lot more drones — i.e. a lot more cheap, long-range strike options on both sides.

The front-line picture is a whole different story, that is being defined by manpower, but if we’re talking about Ukraine's long-range strike campaign, hitting a lot of targets deep inside Russia doesn't have an immediate correlation with hampering Russian offensive operations. Russia's capability to attack along the front line is made possible primarily by the consistent inflow of contract recruit soldiers (complimented by prisoners, foreigners, and coercively mobilized men), along with the firepower provided by drones, artillery, and glide bombs. So long as Moscow can find and redirect resources to keep that flowing, it can continue its war.

Ukraine's long-range strikes are about raising the larger cost of the war for the Russian economy, to cause problems with energy infrastructure at home while working to also choke Russian oil revenue, compelling Vladimir Putin to either stop the war or risk major economic turmoil and instability domestically.

So far, we are seeing results, but — backed up by the cash flows from oil and gas sales — the Russian economy remains more resilient than some people hope or imagine. — Francis Farrell, reporter

Question: As a foreigner, is it more effective to volunteer on the ground in Ukraine with organizations like World Kitchen, for example, or to provide support from abroad? Could you provide resources or a vetted list of organizations in Ukraine that work with foreign volunteers?

Answer: This is a good question — I think ultimately, there are no wrong answers when it comes to helping Ukraine during the war. If you contribute where you can in a way that is sustainable, you’re already making a difference.

To your question, there are arguments that donating to organizations already procuring aid is the most efficient way to support — which may be true — but this doesn’t mean there aren’t benefits to volunteering in person. Volunteering in Ukraine has intangible benefits, like forming connections and friendships or showing Ukraine that people outside the country are still aware of Russia's war and want to help.

I’ve heard from other community members that Volunteering Ukraine has a solid list of organizations that accept foreign volunteers. Earlier this year, we also made a short list of ways to support Ukraine which you might also find useful. — Brooke Manning, senior community manager

Question: Can you recommend some books about the history of Ukraine after 1991, especially EuroMaidan and events leading to the Russian invasion?

Answer: Thank you for the question — there are countless books to choose from, but I’m especially drawn to works that recover people’s history rather than simply retelling events through official records. These books matter because they remind us that history isn’t only shaped by leaders, borders, or laws. It is forged by ordinary people — by their choices, their voices, and the risks they take when the future is uncertain. Let me give you three examples.

Through intimate personal portraits, Marci Shore’s “Ukrainian Night: An Intimate History of Revolution” plunges readers into the cold, electric nights of Kyiv’s EuroMaidan Revolution. Shore captures moments when everyday citizens were forced to confront extraordinary moral choices in the name of dignity and freedom. The book is urgent, haunting, and deeply human — alive with fear, courage, and stubborn hope — and it leads readers into the dark early days of Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.

A similarly unflinching perspective comes from Stanislav Aseyev’s “In Isolation: Dispatches from Occupied Donbas.” Written from inside Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine, this memoir-cum-historical account illuminates what occupation looks like from the ground up: the quiet terror, the daily compromises, and the resilience of civilians living under an imposed new reality after 2014. Aseyev was extremely brave to stay behind in his native Donetsk Oblast to tell the truth about what was happening there, and he suffered greatly for it: The occupation authorities detained him and he spent time in Izolyatsia, a torture camp and literal hell on earth. Thankfully, Aseyev has since been freed.

Likewise, Olena Stiazhkina’s “Ukraine, War, Love: A Donetsk Diary” offers a deeply personal chronicle of the fall of Donetsk. Told through diary entries, it records the shock and disorientation of watching one’s city change hands — and one’s sense of home fracture — as Russian soldiers take control. You can read my full review of that book here.

Taken together, these books do more than document the war. They restore faces, voices, and emotions to history, reminding us that behind every headline is a human life navigating impossible choices in real time. — Kate Tsurkan, culture reporter

read also