As Russia tries to freeze Ukrainians to submission, families try everything to stay warm

Yulia Solonko hugs her daughter, who has just woken up, before changing her into warmer clothes in their apartment in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Jan. 13, 2026. (Elena Kalinichenko / The Kyiv Independent)

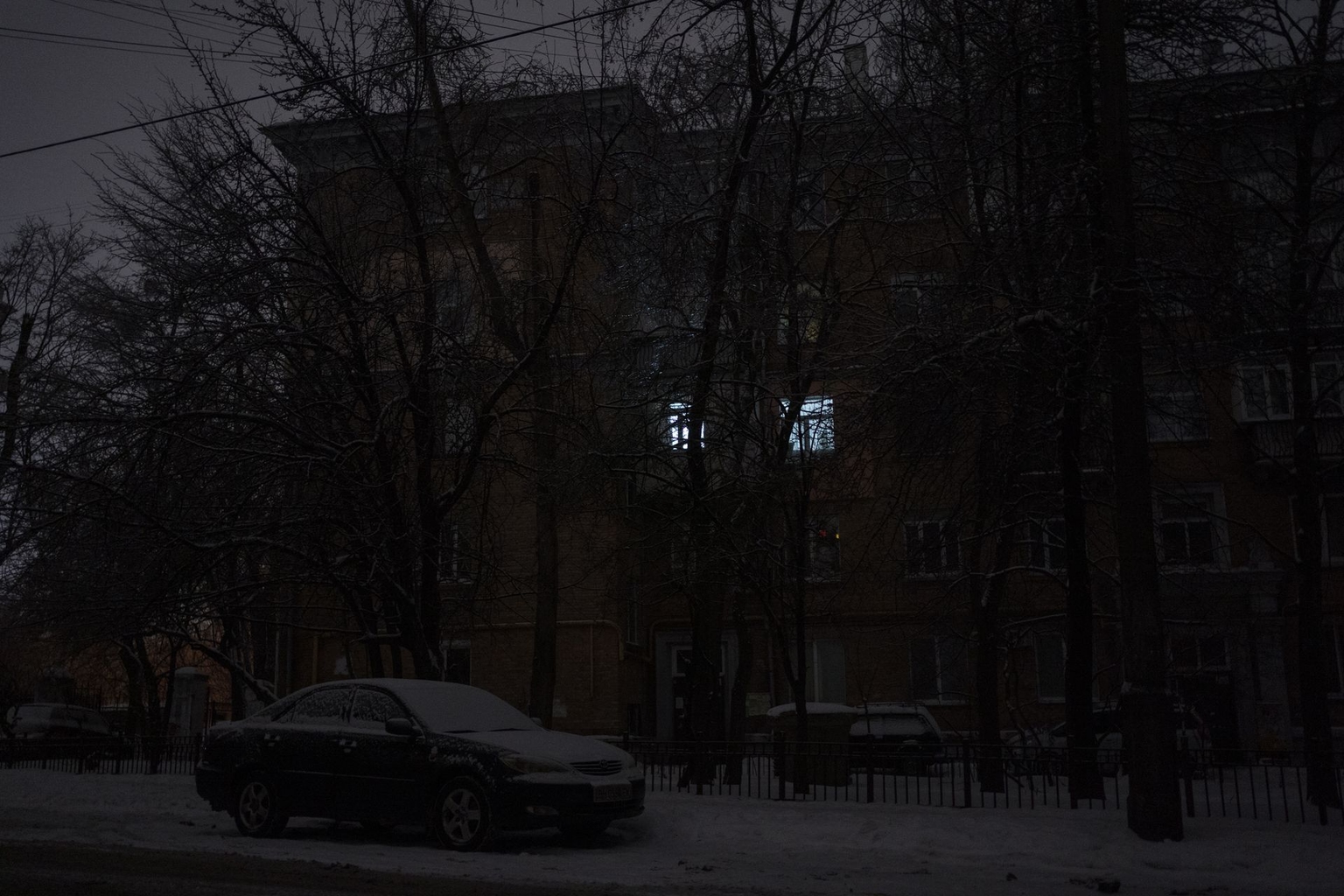

Pechersk is a leafy, affluent neighborhood in central Kyiv. Its prerevolutionary buildings are tucked away from the main roads, surrounded by quiet courtyards and trees. In peacetime, it's where many Ukrainians dreamed of living.

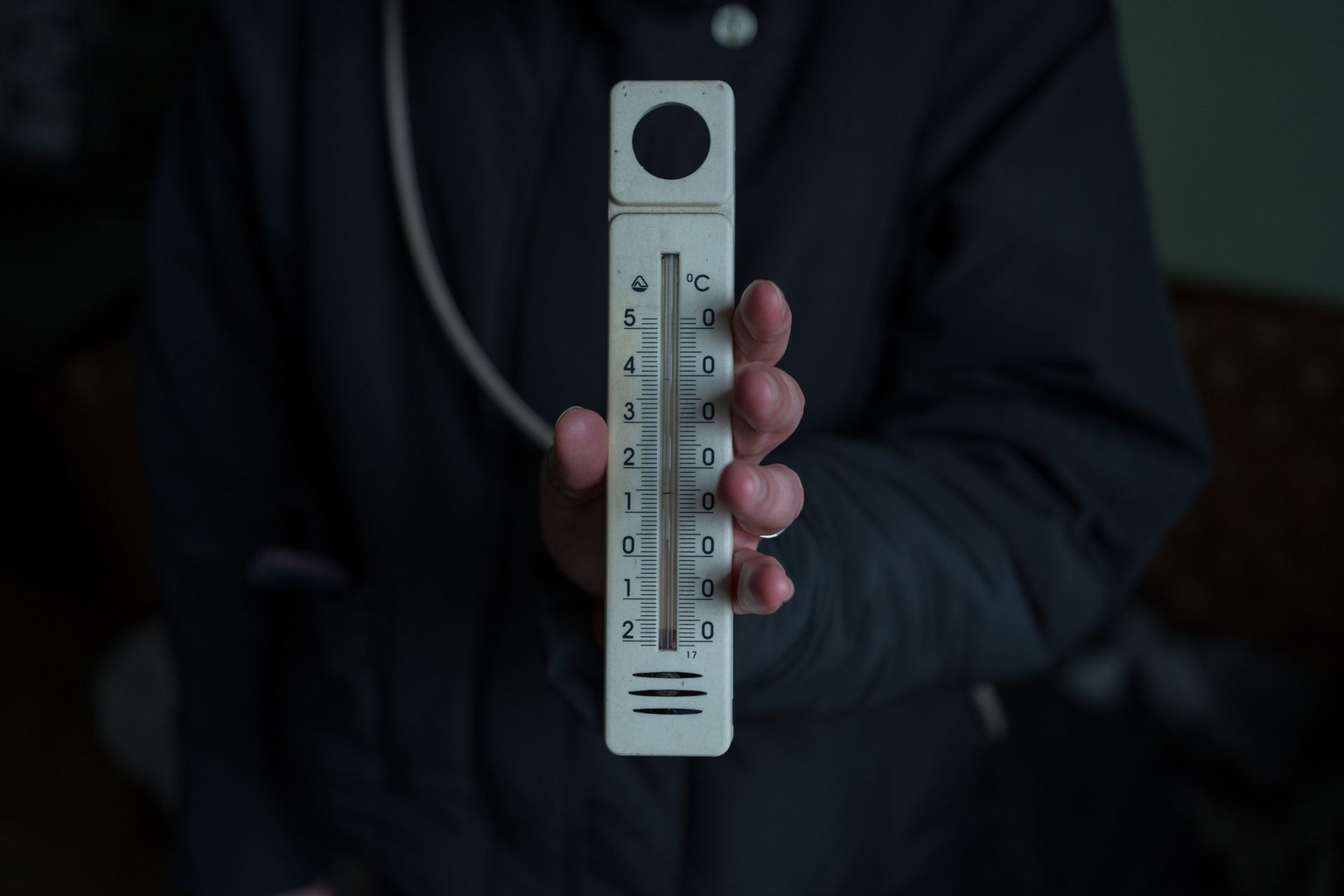

Now, in the fourth winter of the war, it's 3 degrees celsius (37 degrees Fahrenheit) inside some apartments without additional heating, and the temperature continues to drop.

Thick brick walls once insulated the well-off residents from the city's noise — now they make it harder to keep the heat in. Large windows offer a clear view of missile strikes at night and of the total darkness that follows. It's still an elegant building, but after a mass Russian missile strike on Jan. 9, it's barely fit for living.

"This is the coldest winter I've ever known in this flat. Because of the cold, the blackouts, and the constant attacks, it's simply unlivable," said Anna Diachenko, 28, who left the building a few days ago after the mass attack. She's now staying with friends.

The thermometer has been falling steadily every day — from 8 degrees to 5, then to 3.

Russia's strategy is clear: if it cannot defeat Ukraine militarily, it will try to freeze it into submission.

Ukrainian officials describe Russia's winter strikes as "weaponizing winter." President Volodymyr Zelensky said on Jan. 9 that Russia was exploiting the cold snap to hit as many energy facilities as possible, while Ukrenergo CEO Vitalii Zaichenko said Moscow was trying to "disconnect the city" and force people to leave Kyiv.

On Jan. 14, Zelensky announced a state of emergency in the country's energy sector.

Systematic attacks on Ukraine's energy infrastructure have intensified since 2023. Power plants, critical infrastructure, residential buildings all become targets. With every blackout, Russia is trying to send Ukraine a message — your government can't protect you, accept our terms, pressure your leaders to settle for "peace."

The stakes are higher every time. So is the strategy working?

"Of course not. We know that it's hard because of Russia," Diachenko said flatly.

Andriy Tartyshnikov, 33, a cinematographer who lives just one floor below Diachenko, said that if the strategy has any effect at all, it's only to make people angrier at Russia.

"The authorities and services are doing what they can, and people understand that. No one here is blaming them. Every day, we feel more hate and anger towards Russia. It won't make anyone surrender," he said, standing in several layers of clothing, a hat, and thick socks in his spacious studio apartment.

Tartyshnikov and his neighbors have heaters, lamps, power banks, and backup battery systems. From there, it all depends on the situation, the resources, and a bit of creativity.

People use everything from stuffed toys to plug gaps in windows, to ancient heating methods involving fire and stones.

Survival hacks

Roza, a French bulldog, is the main source of warmth for Olena Bazylska, 43, an office manager, and her partner.

Roza herself is freezing too. She wears dog clothes around the apartment and sleeps at night between Olena and her partner.

"Sometimes I do push-ups off the floor when it gets too cold,"

Olena Bazylska is seen in her apartment in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Jan. 13, 2026. (Elena Kalinichenko / The Kyiv Independent)

Olena works from home in three layers of clothes. On the fourth day without heat, she gave up trying to keep the whole place warm and shut all the doors. Now she lives in the living room. It's her bedroom, her kitchen, and her office. It's a workday, and Olena is put-together — wearing a rosy, cozy sweater, her hair carefully done.

"Sometimes I do push-ups off the floor when it gets too cold," she said.

In the hallway, a string of fairy lights runs along the wall, all lit up. It's a sign that there is no electricity.

"They're not about the holidays. They only turn on when the power goes out," Olena said.

Andriy Tartyshnikov's main room is combined with the kitchen, so he heats it using the gas stove. It runs on gas, not electricity, and still works during outages.

"I turn on the stove, place a brick on top, and a big empty cast-iron pot over it. After a few hours, the temperature goes up by about 4 degrees. In the morning, it was 12 degrees here. Now it's almost 16," Andriy said.

At night, he sleeps at his father's house outside the city. The only things still "living" in his apartment are his plants — two tall ficuses, a monstera, a banana plant, and some others — all in winter dormancy.

One ficus now stands right in front of the wall where his home cinema projector used to light up.

"I don't use the projector now, obviously. I'm not staying here overnight. I moved the tree out of the bedroom. It's way too cold in there," he explained, lighting an incense stick, then setting a pot on the stove for tea.

It's a carefully arranged winter habitat, perfect for living, if not for Russia. As of Jan. 13, it's 3 degrees in the bedroom.

One warm room

On the second floor, Yulia Solonko, 37, is doing what many parents in Ukraine are doing this winter — staying put, because leaving is not simple when you have two small children. Her husband lives elsewhere for work.

Her relatives offered her family a place in Spain, but the logistics were overwhelming.

Instead, she turned one room of the apartment into a warm zone for her daughters — nine-year-old Zarina and two-year-old Svyatoslava — layering the space with blankets and toys. Above the bed, a sheer pink curtain floats in place. The whole space feels wrapped in a mother's quiet care.

"I hung up a bunch of clothes, kids' dresses, on the entrance of the room to keep the heat in. The floor is warm because there is a lab downstairs, and their generator runs all the time. We shoved pillows, blankets, and all the soft toys we had into every possible gap. I go out in a winter coat, usually just to the kitchen for food," she said.

Sometimes, they shower at a local gym. Today, there was a bit of light and hot water. Her older daughter had a warm bath around 5 p.m. and came out pink-faced and drowsy from the heat.

"When are the new 'Avengers' coming out? Is it still a long wait?" Zarina asked. "Can we turn on the heated blanket?"

"There's no power," her mother replied. "I'll wrap you up with normal blankets."

On the edge

But what if it gets worse? Despite the city's residents having adapted well, the situation remains critical. Kyiv mayor Vitali Klitchko has urged people to consider leaving temporarily if they have other options.

"The only thing keeping me here is my loved ones — my mom, my sister, my friends. If something happens to them, I'll leave. Loss stays with you forever," Diachenko said.

"The only thing keeping me here is my loved ones — my mom, my sister, my friends."

Anna Diachenko is seen in her bedroom in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Jan. 13, 2026. (Elena Kalinichenko / The Kyiv Independent)

Tartyshnikov, by contrast, returned from Germany. He holds a Latvian passport, so he can legally leave the country, but chose to come back. He believes adaptation is the only option, because war can eventually reach other countries, too. He adapted by replacing a career in film with documentary work.

"No one will be investing in cinema, no one will have the time. Everyone will be busy fighting," he said.

Renewed assault

Even with cosy setups, fairy lights on the walls, and kids waiting for the next Avengers movie, the neighbours are not just skeptical about the war ending soon, some are preparing for a renewed assault on Kyiv.

"The question isn’t if, but when. When they decide to come for Kyiv again, I’ll evacuate my kids. Because next time, they won’t be coming for a three-day parade," Solonko said.