Inside Ukraine's desperate race to train more soldiers

Ukrainian recruits train at an undisclosed location during basic military training on Oct. 30, 2024. (Patryk Jaracz / The Kyiv Independent)

New recruit Vitalii Yalovyi knew one thing after completing the Ukrainian military's boot camp: He was not prepared for war.

The 37-year-old felt physically unfit, forcing him to miss some courses during the month-long training. His leg was still hurting from long daily walks at a training center in western Ukraine. But instead of getting an MRI scan after the training course as planned, he was taken on a bus, not knowing where he was heading.

The "Welcome to Russia" road sign gave him a clue. The bus was driving into the Ukrainian-occupied part of Russia's Kursk Oblast, where Kyiv launched a surprise cross-border incursion in August 2024.

Scared of being immediately thrown to the front line, Yalovyi warned his commanders that he didn’t have basic soldiering skills, and couldn’t shoot properly.

The overcrowded boot camps and the instructors' lack of motivation often prevent the fresh recruits from getting enough hands-on practice, leaving them uncertain about whether they are actually prepared to fight a war, according to Yalovyi and other new soldiers’ testimonies.

Yalovyi immediately found himself at the forefront of the Kursk battle. Three weeks later, he said he was the last person at the position after about a dozen others fled in different directions following Russia’s gas attack. He was lost.

"I really thought I was done," Yalovyi said, describing how he had no idea how to retreat.

Eventually, Ukrainian soldiers from nearby positions found Yalovyi and brought him back to Ukraine. Many others who were sent to the front line without proper training weren’t as lucky.

Three years into Russia's full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian military faces an endemic manpower shortage and is forced to scramble for people to fill in the gaps in the infantry depleted by the war.

Commanders on the ground have said, however, that they are increasingly receiving soldiers who fight as though they have never been trained. Lacking basic survival skills, such as using an anti-night-vision blanket to avoid being spotted by the omnipresent drones, new recruits are “often killed or wounded” in the first weeks, according to over a dozen officers interviewed across the front line.

The sink-or-swim situation, in which recruits either make it out alive by learning on their own or face casualties, is costing a horrifying level of losses, the interviewees say. They stressed that it has also led to the loss of positions that had cost lives to defend for months or years, often demoralizing the battle-hardened troops as a result.

Glen Grant, a retired British Army lieutenant colonel who advised Ukraine's Defense Ministry on and off from 2014 to 2018 and has been closely observing the military issues since, said no one holds responsibility when recruits face heavy casualties in the beginning, and there is still no established way of independently monitoring the quality of the training provided.

Calling Ukraine's training system "ad hoc" and a "you do it as you get there" strategy, Grant said troop preparation lacks a system that ensures recruits get the most out in a limited timeframe.

"People die when you do stuff ad hoc," Grant told the Kyiv Independent.

The Kyiv Independent visited five training centers and spoke to dozens of soldiers, officers, and instructors on and off the record to uncover the critical issues in Ukraine’s race to prepare fresh recruits.

Recruits 'run out quickly'

The biggest challenge in training new recruits in a war that constantly changes is that the battlefield survival skills quickly become outdated, according to the training center instructors and officers on the ground.

From the rise of first-person view (FPV) drones to the changing Russian assault tactics that increasingly rely on manpower, there needs to be "a constant exchange of information" between the battlefield and training centers, instructors at multiple training centers told the Kyiv Independent.

Adjusting the official Ukrainian military training program — now in its fifth edition, updated in February — to reflect the current situation is not easy due to the bureaucracy in the army leadership, according to those familiar with the matter.

"(New soldiers) run out quickly, even before they get to the line of contact."

Following the training, now taking 1.5 months, the recruits are supposed to spend two weeks on the second line or in the rear before their first deployment on the "zero" line to adjust to the front-line conditions in relative safety, according to Ruslan Gorbenko, a lawmaker from the ruling Servant of the People who regularly travels to the war-torn east and keeps in touch with the military. But it rarely works in practice.

Multiple company commanders deployed in the eastern Donetsk Oblast said their personnel losses are so high that on the rare occasions they receive reinforcements, they are forced to send them to the "zero" line immediately to finally relieve the soldiers stranded there for weeks.

The new soldiers, unfamiliar with the extremely intense front-line conditions under a constant barrage of FPV drones, aerial bombs, and artillery, face much higher casualty rates than those serving for months and years.

"(New soldiers) run out quickly, even before they get to the line of contact," Oleksii, an officer with the 109th Territorial Defense Brigade, said. Some of those interviewed declined to give their full names due to security concerns and the sensitivity of the topic.

Those who survived their first combat missions often lose motivation after seeing the high casualty rates among their group, sometimes refusing to go back to the front, according to Oleksii.

"(The new guys) can run somewhere, and that is the worst thing that can happen when someone is panicking," Bohdan, acting company commander with the 214th Separate Special Battalion OPFOR, told the Kyiv Independent.

"The people are not morally or physically ready, especially the older people," he said, referring to men over 45, an age group that most of the new recruits belong to, according to the officers interviewed.

One officer, who has served since Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014 and spoke to the Kyiv Independent on condition of anonymity, stressed that the Ukrainian army needs to move away from the Soviet mentality and value every soldier's life equally.

The whole process, from recruiting to preparing soldiers for war, should reflect this principle, he added.

"First of all, (people) are a resource that we will not be able to restore, and (a serviceman) is extremely valuable in principle, both for his family and the army," the officer, who serves in one of the most prominent units in Ukraine’s Armed Forces, told the Kyiv Independent.

One particularly concerning issue, he said, is that miscommunication can happen on the ground due to front-line units' inability to operate as "one organism," which increases the risks of friendly fire.

It is sometimes difficult to track whether the surrounding positions are friendly, especially if certain groups flee without warning. Inadequately trained soldiers, who are more likely to panic, are at a higher risk of either inflicting or becoming casualties in such circumstances.

A source who worked in the Defense Ministry until 2024 also confirmed, on condition of anonymity, that poorly trained troops had proved to be more susceptible to opening friendly fire.

The Ukrainian military leadership disagrees that the quality of training leads to such incidents on the battlefield, denying the issues with troop preparation.

Colonel Yevhen Mezhevikin, the deputy head of the General Staff's Training Directorate, argued in turn that it is the commanders' responsibility to ensure that the new soldiers are given the time to adjust to the war and are ready for it. If the commanders see that the new soldiers are ill-trained, they should report it to the higher command to identify the training center for feedback, he added.

Many factors affect the recruits' survival rate beyond the quality of the training, including the intensity of the deployment location and the commanders' ability to lead their troops, according to Mezhevikin.

"We did our best to improve the training of servicemen, and (after the training), we give responsibility to the commanders to train them in their military units," Mezhevikin told the Kyiv Independent, stressing that training should be a continuous process throughout the deployment.

In their turn, soldiers and officers emphasized that there should be more inflow of information from the battlefield to the training centers, which can be disconnected from the reality on the ground. New recruits often don’t have crucial knowledge like how to carry oneself during a drone attack or survive open-trench warfare.

Colonel Mezhevikin said that there is a way for brigades in different deployment areas to pass on real-time knowledge to training centers, and the military's Unmanned Forces Command is regularly sending in updates on Russian drone usage to reflect the reality at the front.

Mezhevikin, who formerly commanded the elite Adam Tactical Group drone unit, admitted that it is largely impossible for recruits with no prior military experience to suddenly turn into soldiers who can take on any task in a month, which is how long the training lasted until recently. He stressed that the necessary changes to improve the procedure have been implemented.

The General Staff extended the training period from one to 1.5 months in late 2024, which is still half of the pre-war duration. Mezhevikin said all training centers have implemented it as of February.

Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi said in December that there were plans to extend it to two months, but it has yet to happen.

Extending the program by half a month caused certain gaps in troop replenishment, but it gives recruits more practical training, which now accounts for 90 percent of the program, according to Mezhevikin.

Instructors at five training centers visited by the Kyiv Independent said that they have a feedback loop with the former recruits and combat brigades to constantly assess the situation on the front and make the needed adjustments.

Unmotivated instructors, overcrowded training grounds

Extending the training period alone without increasing its effectiveness — such as improving the quality of the training staff and the process itself — won't necessarily improve the situation, experts following Ukraine's troop training process say.

The lack of motivation and the overload of the existing training grounds are the prime reasons for the knowledge gaps of some of the recently mobilized soldiers, according to the interviewed officers.

President Volodymyr Zelensky admitted in July 2024 that there is a lack of training facilities for new soldiers but vowed that "they are already being expanded."

Around 30,000 recruits were at training centers across Ukraine, as of the end of February, according to Mezhevikin. Faced with an overwhelming number of recruits that training centers didn't expect until the outbreak of the country-wide war in 2022, the training grounds and the available instructors are still overstretched.

Even if the number of training hours on paper sounds adequate, the recruits often spend time waiting for their turns in long lines, dry firing or simply watching. Recruits sometimes don't have the opportunity to ask questions or have their techniques corrected, which could be detrimental on the battlefield.

A group of recruits at one of the training centers in western Ukraine told the Kyiv Independent that they wished they had spent more time on clearing trenches because they only had one day allocated to that. Due to the large group size, only a few of them actually tried it out — and the rest watched.

Basic training should include more practical elements, including how to build positions and conceal oneself from potential attacks, according to an ex-British Army soldier currently fighting with Ukraine's military, who asked to remain anonymous due to his unit’s protocol. Observing how new Ukrainian soldiers operate on the ground, he believes more trench warfare practice should be incorporated to get "a sense of how it works in a battle."

The officers the Kyiv Independent interviewed accused the training centers’ leadership and the military command of failing to improve the preparatory system while knowing about the problems. They blamed it on the “Soviet mentality” of the military command and the system’s vast bureaucracy.

Key issues in the Ukrainian military's basic training include unmotivated and "severely burnt out" instructors who often lack battlefield experience, independent inspections to assess the quality of preparations and training facility conditions, according to researchers at Come Back Alive Foundation, who studied the boot camp program in 2024.

The foundation's senior researcher, Serhii Bahlai, called it a "complex problem." While the problems are clearly identified, the military command and training centers’ leadership on the ground are reluctant to change their approach, he said.

The issues are "fixable but require effort," according to Bahlai, who mentioned situations where an instructor oversees around 100 recruits at a time.

Mezhevikin, in turn, denied that instructors were overwhelmed with recruits, saying that the ratio is usually eight to 10 recruits per instructor and that extending the program duration helped reduce their stress with paperwork.

Colonel Valentyn Khomenko, who is the deputy head of the Rivne training center, dismissed complaints about the practical aspect of the training program and that the facilities are overcrowded. He attributed the biggest challenges to the recruits' attitude.

Khomenko estimated that at least 50% of the recruits arrive unmotivated to train and join the war efforts, often because they were forcefully mobilized, and it takes them time to understand why they need to fight as they slowly begin to absorb the basic soldiering skills.

Some recruits see the war as "a one-way ticket," and it is understandable that they are unmotivated to adjust to the "spartan conditions" at training centers, the officer from one of Ukraine's well-known battalions told the Kyiv Independent.

Instructors at multiple training centers said that the hardest part is usually breaking the “civilian mentality,” and helping the recruits switch to a military mindset — which includes accepting the new limitations on personal freedom, and the need to constantly assess the consequences of one’s actions. This change is especially hard for those mobilized against their will. Some recruits said they spent their first days being angry that they were drafted, wondering what they could have done to avoid it.

Instructors admitted that it is difficult to train recruits who are unwilling to learn.

Fearing the loss of more lives that could be avoided with proper preparation, servicemen and those working closely with the training process have advocated for a change.

The interviewees often say that they faced an obstacle with the General Staff, which, they say, has been largely closed off to outside suggestions. Some blamed the "negligence" of both the General Staff and the Defense Ministry for not addressing the issue sooner.

"The system is built in a way that no one takes responsibility for poor training," according to Roman Donik, the head of the private 151st Training Center certified by the military.

Mezhevikin said that the military implemented the necessary reforms, and the General Staff is awaiting more feedback from on-the-ground troops to continue improving the training program. He added that there is a hotline and complaint form available with either the General Staff or Defense Ministry in case the training centers are not fulfilling the recruits' needs.

The phone usage rules vary across training centers, with some centers banning phones or limiting usage to a few hours a day. Recruits also don’t always have stable internet access due to the poor cellular network at the remote training facilities.

Training facility limitations

Logistics are often another issue at training centers, which force the recruits to walk kilometers a day between the training grounds and the living quarters, according to Come Back Alive researchers.

Often located far from each other for safety reasons amid Russia's constant air strike threats, recruits live in tents far from the training grounds and spend a long time simply walking between the sessions — which they say consumes time and energy that could be spent elsewhere.

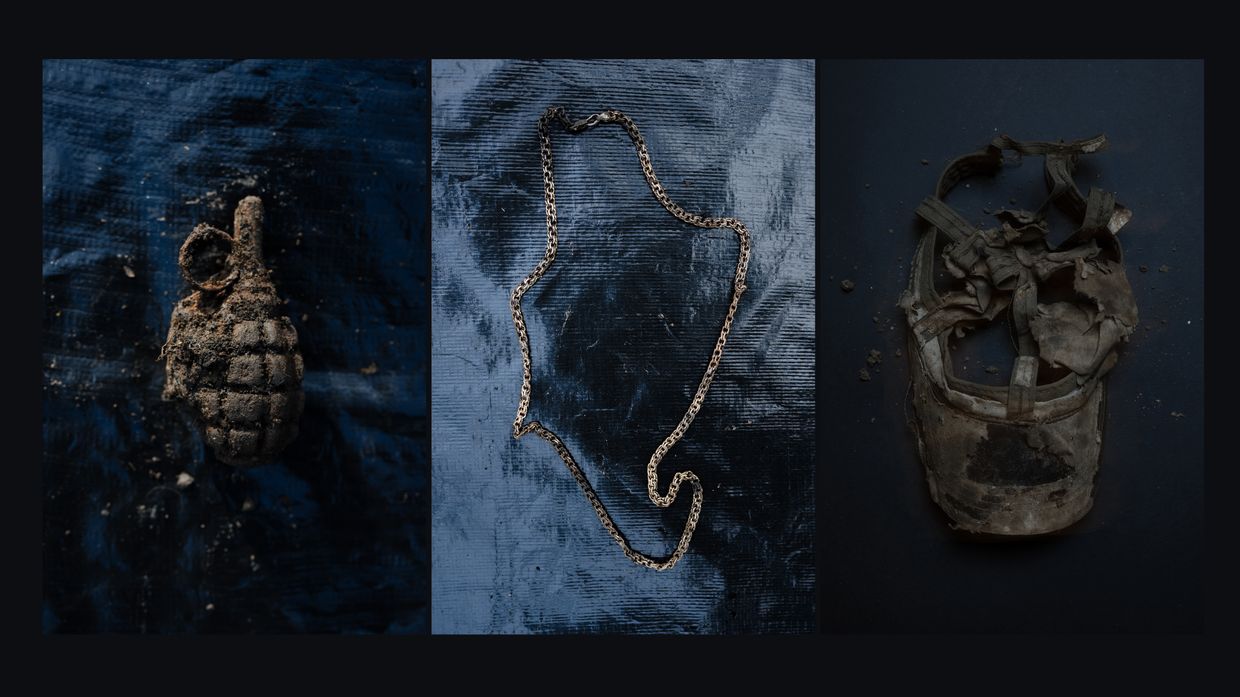

Russia has targeted multiple training centers across Ukraine with missiles, with the first such attack in March 2022 killing over 60 people at the Yavoriv military training ground in Lviv Oblast. Aftermaths of Russian missile and drone attacks were visible at some of the training centers visited by the Kyiv Independent, where those in charge said the facilities had been hit and there had been casualties.

With the Ukrainian troops mostly having moved out of the barracks, sanitary concerns were occasionally raised by the recruits at often overcrowded tents. The recruits usually have to maintain their living areas on their own, which may lead to sanitary issues and be a distraction from the core part of training, according to Bahlai from Come Back Alive. During winter, fresh recruits often get sick immediately and miss the vital first days of training.

The training centers that the Kyiv Independent was allowed to visit, however, appeared clean. The recruits there typically sleep on bunk beds in large tents, usually housing a few dozen recruits each, sometimes at relatively cold temperatures in winter.

Mezhevikin said that the conditions are "livable," but there would ideally be containers rather than tents so the recruits could rest in a more comfortable and warmer environment.

Grassroot initiatives

With the training of freshly mobilized recruits being constantly brought up as one of Ukraine's weak spots in the military, some minor improvements have been made to help fix the situation on the ground.

One of the large training centers, for example, incorporated VR headsets to illustrate a brutal reality on the front, where other guys lose their limbs and cry for help in agony.

Yet, volunteers still try to do the heavy lifting.

Magnus Ek, an instructor from Sweden, is among those giving additional training to Ukrainian soldiers on the ground, after they arrive from the boot camp. After training roughly 2,000 soldiers since 2022, Ek said it is "a big tragedy" that soldiers often lack basic training, including shooting practice.

"Everything" is missing, including tactical medicine training, which means recruits use the tourniquets incorrectly which can cost a limb on the front line, according to Ek, who spent 12 years in the Swedish Army.

He stressed that the Ukrainian military leadership should "listen more to the front line" because the average soldier's skill sets appear to be "terribly low," and proper training could reduce casualties.

Ek believes that it is very easy to change the training situation, especially with particular examples, such as the Azov Brigade and Third Assault Brigade, now relabeled as Third Army Corps, which have successful training programs. Understanding the issues in the basic military training, some of Ukraine’s most elite units have built their own in-house training systems to prepare their recruits.

"We have all the elements to change this very quickly," Ek, former lieutenant in the Swedish Army, told the Kyiv Independent. "We have the experience, the knowledge."

Yet, soldiers and trainers speaking with the Kyiv Independent say they see no will for change in the military leadership.

Kyrylo Berkal, deputy commander of the Third Army Corps, who oversees training, stressed that the major problem is that the “Soviet roots” that still persist in most centers, even if their programs appear to be more modern.

The officer said that the issues are also in the lack of intensity at training centers, especially compared to the real war conditions, and low motivation among instructors, likely due to low pay and the overwhelming amount of work.

“The main problem is the Soviet approach,” Berkal told the Kyiv Independent, referring to the obsolete tactics introduced during the program and the instructors’ mentality. “In training centers, the attitude towards the system is very outdated.”

A private training center in Kharkiv Oblast, run by Donik, said he faces more obstructions than support from the official training centers. He named bureaucracy as the biggest obstacle in continuing operations and expanding them.

"The combat ability of a brigade is directly affected by the preparation of recruits," Donik told the Kyiv Independent.

"We are losing a lot of time and people."

Note from the author:

This is Asami from the Kyiv Independent. Thank you for reading the story.

I've worked on the story for more than half a year, and it was certainly difficult. I often heard about the issues in the military training system, but delving into it and trying to lay out the issue as transparently as possible was quite challenging. My colleagues and I are working around the clock to bring you the latest updates, whether they're good or bad.

Please consider joining the Kyiv Independent community. Your support helps sustain our work.

Thank you.