As the dust settles over Munich, Ukraine and Europe face collapse of post-Cold War order

(L-R) British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and France’s President Emmanuel Macron attend the start of an E-3 meeting during the Munich Security Conference in Munich, Germany, on Feb. 13, 2026. (Kay Nietfeld / Pool / Getty Images)

The U.S.-Europe dynamic was more cordial at the Feb. 13-15 Munich Security Conference than last year, with U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio delivering a conciliatory speech.

But the substance of the relationship remained unchanged, despite the softer rhetoric.

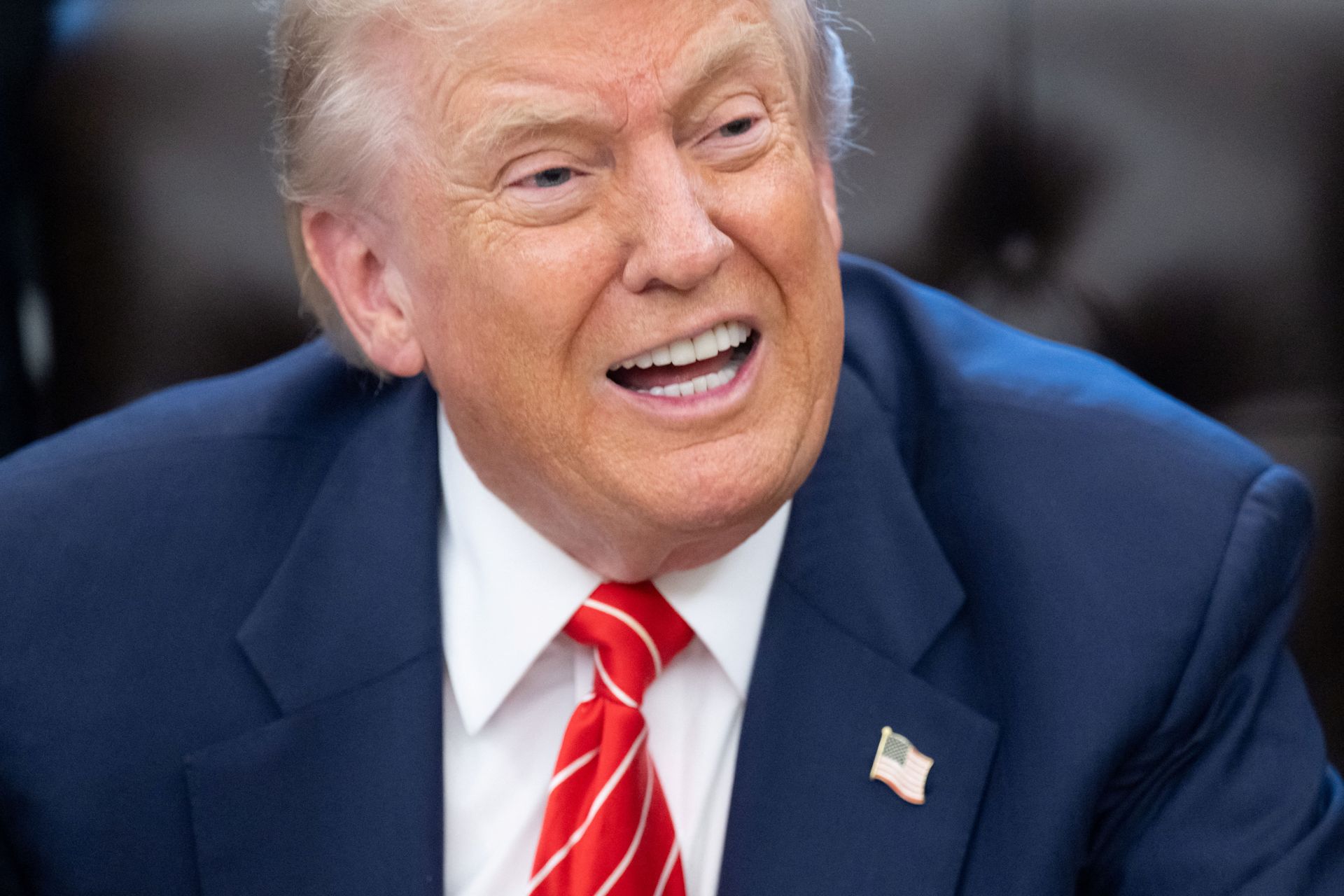

U.S. President Donald Trump's foreign policy upheavals, from Ukraine to Greenland, were fresh on everyone's mind – as well as the confrontational address by U.S. Vice President JD Vance during last year's conference.

European leaders made it clear: the post–Cold War global order is ending — or at least undergoing profound change — and Europe can no longer afford to remain in Washington’s shadow.

"If there had been a unipolar moment after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a unipolar moment in history, it has long passed," German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said in his speech, heralding the return of "power politics" and warning that the U.S. cannot "go it alone."

French President Emmanuel Macron, in turn, urged Europe to become a “geopolitical power,” while hinting at reforms to France’s nuclear doctrine as Paris weighs extending its nuclear umbrella over the continent.

With Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in attendance, Russia’s invasion was still on the agenda, though partly overshadowed by broader global turbulence and a transatlantic rupture.

The Munich Security Conference also painted a bleak picture of peace prospects for Ukraine, contradicting the recent optimism from U.S. officials. Furthermore, some officials and analysts cast doubt on whether the U.S. and Europe could provide Kyiv with NATO-style security guarantees.

The transatlantic wake-up call

Despite the bold calls for European autonomy, there was clear relief when Rubio, the most senior U.S. official present, delivered a speech markedly different in tone from Vance's.

"So in a time of headlines heralding the end of the transatlantic era, let it be known and clear to all that this is neither our goal nor our wish – because for us Americans, our home may be in the Western Hemisphere, but we will always be a child of Europe," the U.S. diplomat said in a speech met with a standing ovation.

Nevertheless, some noted that Rubio was delivering a familiar Trumpian message, simply packaged in more diplomatic language.

"Secretary Rubio said exactly the same things (as Vance), just in a more polite way," Estonia's Foreign Minister Margus Tsahkna told the Kyiv Independent on the sidelines of the event, referring to the American's calls for a stronger Europe.

The Estonian official acknowledged that some U.S. criticism is warranted — and even useful — and described Europe as a former athlete “getting fat” from inactivity.

"We just need to start training… We have more strength to act on defense, but also on an economic level," Tsahkna said. "And also Ukraine is part of our future — a huge opportunity."

In fact, few European officials have challenged Washington’s call for Europe to rearm, as reflected in last year’s pledge by NATO members to raise defense spending to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP).

But the U.S. message has been muddled by a simultaneous push for a weaker EU, Washington's support for far-right and populist parties, and a brief threat to impose U.S. tariffs on countries that opposed Trump's bid to annex Greenland.

Notably, after his appearance in Munich, Rubio traveled to Slovakia and Hungary — arguably the two most Kremlin-friendly EU member states, both heavily reliant on Russian energy.

No high hopes for Ukraine talks

Despite recent optimism from U.S. envoys, the Munich Security Conference cast a gloomy picture regarding progress toward peace in Ukraine.

As the conference took off, Trump called on Zelensky to "get moving" with peace talks ahead of trilateral negotiations in Geneva on Feb. 17-18, claiming that "Russia wants to make a deal."

But Moscow has dismissed key elements of a peace framework drafted by Ukrainian and Western officials, refusing to compromise on its territorial and political demands.

In Munich, Rubio's message was out of step with his boss's.

"We don't know if the Russians are serious about ending the war," the U.S. diplomat said, while Zelensky asked the attendees: "Can you imagine (Russian President Vladimir) Putin without war?"

"No one in Ukraine believes he will ever let our people go. But he will not let other European nations go either – because he cannot let go of the very idea of war," the Ukrainian leader said, warning that carving up Ukraine through territorial concessions would not bring a lasting peace.

In contrast with his scathing remarks about Europe in Davos, Zelensky thanked European allies for stepping up military support as the U.S. withdrew. He also said that it is a "big mistake" that Europe is absent from the negotiating table.

Many echoed this message. In an interview with Bloomberg in Munich, Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski complained that Europe is being sidelined from negotiations even though it – not the U.S. – foots the bill for Ukraine's defense.

Last year, the U.S. halted nearly all new aid allocations, while European military support surged by 67%, including through purchases of American hardware for Ukraine. The Munich conference also followed U.K. Defense Secretary John Healey's announcement of $35 billion in fresh allied assistance this year.

Missing answers

Zelensky and Rubio met on the sidelines of the event to discuss air defenses, Russia's escalating attacks on Ukraine's energy grid, and the upcoming round of peace negotiations.

"We also touched on the sequence of steps. It's important to make progress on issues of security guarantees and economic recovery," Zelensky said after the meeting.

At the conference, the Ukrainian leader called for 20-year security guarantees to be signed before a potential peace agreement, a sequence that clashes with Washington's push for the fastest possible end to hostilities.

Although the West has previously signaled readiness to provide Ukraine with “Article 5-like” security guarantees, backed by a post-war European-led multinational force, officials who spoke with the Kyiv Independent were cautious.

"The primary security guarantee is strong Ukrainian armed forces," Latvian Defense Minister Andris Spruds told the Kyiv Independent in an interview.

The deployment of forces led by the Coalition of the Willing would additionally demonstrate Europe's engagement, the Latvian defense chief said. He declined to speculate on what would happen if a Russian missile struck the said troops.

Lithuanian Foreign Minister Kestutis Budrys warned against offering "hollow" promises and "fake guarantees" to Kyiv. In an interview with the Kyiv Independent, he dismissed the concept of Article 5-like guarantees, calling them mere "rhetorical expressions."

"There can be nothing similar to Article 5… Because Article 5 means that if you are in trouble, I promise you that I will come and if it is needed, I will die for you," he added.

Instead, he underscored financial support for Ukraine's Armed Forces or Ukraine's future EU membership as more realistic guarantees.

The question remains: what security guarantees — short of direct Western military involvement — would deter Russia, given that extensive security aid and sanctions have failed to end the war?

U.S. political scientist Ian Bremmer said he does not consider the proposed security guarantees credible.

"Trump has shown that he is willing to throw Ukrainians under the bus, repeatedly," Bremmer told the Kyiv Independent.

He added that the U.S. president appears determined to end the war and claim political credit — without putting American lives at risk.

But even if Europe — backed by Washington — were to formally commit to military intervention, the expert said he "can't see the Russians accepting that today."

Bill Browder, an American-born British financier and sanctions advocate, expressed skepticism that Moscow would relent in 2026, despite mounting economic woes.

"I think if we just were to watch the pressure that they're under right now, going into 2026, I don't think that's enough to stop them in the war in Ukraine," he told the Kyiv Independent.

Comparing Putin to North Korea, Browder said: "He will always have enough money for his war, even if he has to starve his population. So, you need to make sure that he just doesn't have enough money for anything."

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Martin, the author of this article.

The Kyiv Independent has no paywall, no wealthy owner – our work is driven by readers like you. If you want to keep seeing us deliver on-the-ground reporting from key events shaping global security and politics, please consider supporting us by joining our community of paying members.

Thank you!