On the battlefields of eastern Ukraine, with the first days of March came the all-consuming mud. Videos of trucks and armored vehicles bogged down in fields heralded the arrival of a time traditionally known in Ukrainian as bezdorizhzhia, or “roadlessness.”

Though the mud may present a brief challenge to both Russian and Ukrainian operations for a few weeks, it also marks the beginning of the spring 2023 campaign in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Over spring and into summer, both sides are expected to make major offensive moves to take territory and grasp the initiative as the full-scale war enters its second year.

Both sides have reasons for confidence in success on the battlefield.

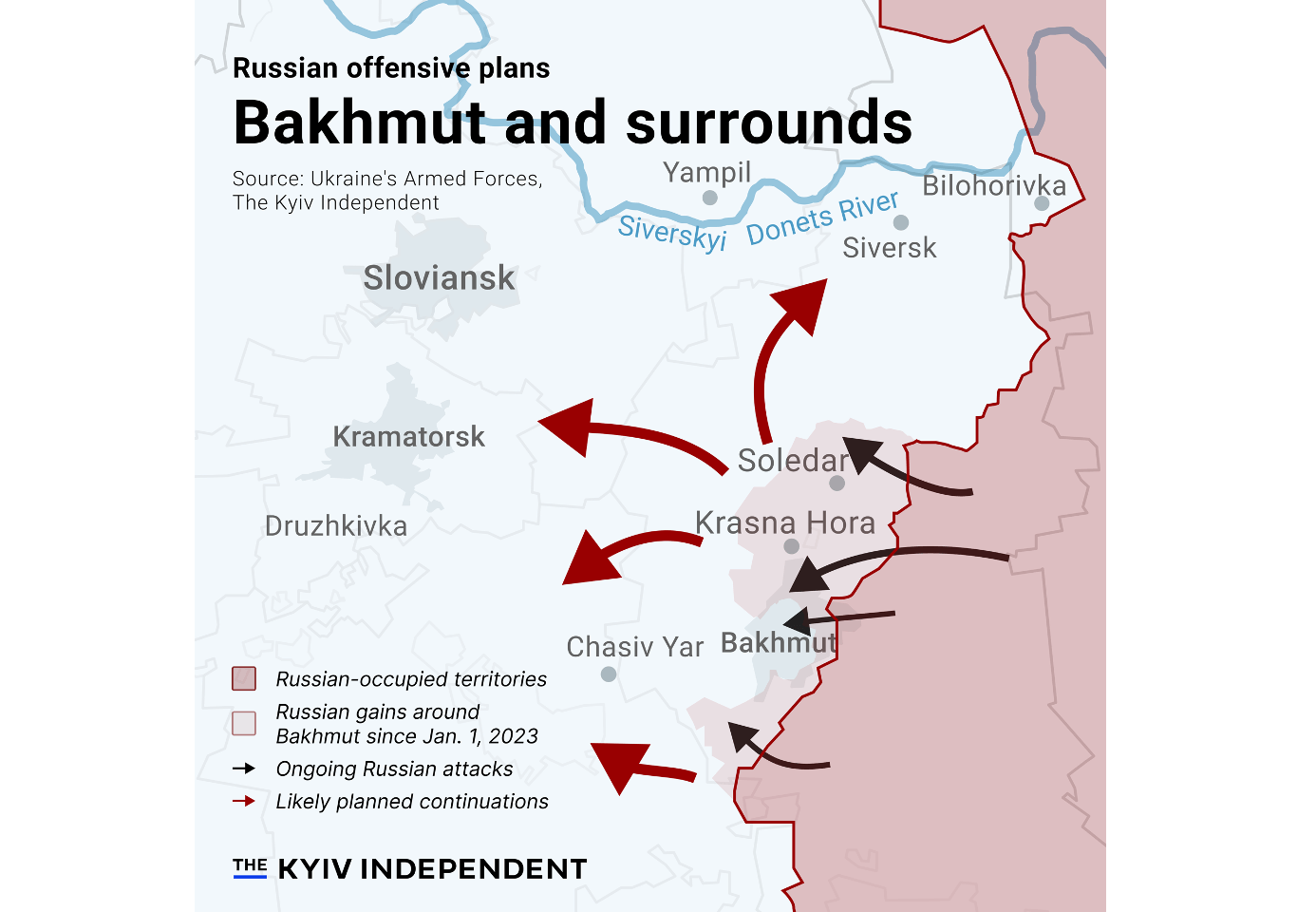

Over the past two months, Russia, using vast quantities of infantry, artillery and armored vehicles, is on the verge of finally capturing the “fortress city” of Bakhmut in Donetsk Oblast after a months-long assault.

Taking Bakhmut would represent the first major Russian gain since the capture of nearby Lysychansk over eight months prior, and the only significant change of territorial control since Ukraine’s liberation of Kherson and the surrounding areas on the western bank of the Dnipro River in November.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s Armed Forces eagerly await the arrival of over 100 Western-built tanks into their ranks, after partners’ consistent refusal to provide the weapons was dramatically broken with a flurry of pledges in January.

Complemented by several hundred more Western armored vehicles to be delivered around the same time, German-made Leopards, British Challenger 2, and American M1A1 Abrams tanks are expected to provide Ukraine with the high-tech offensive spearhead needed to break through well-prepared Russian defensive lines.

Ebbing and flowing through phases, the course of the first year of the all-out war was notoriously hard to predict.

By now, the rules of the game have been established, and the resources, strengths, and weaknesses of each side are clear.

The final outcome itself of the spring/summer campaign is far from certain, but what develops in the first half of 2023 will likely set the tone for the rest of the war.

Russian offensive: One month in

Russia’s much-anticipated 2023 offensive began before many noticed, in the depths of winter.

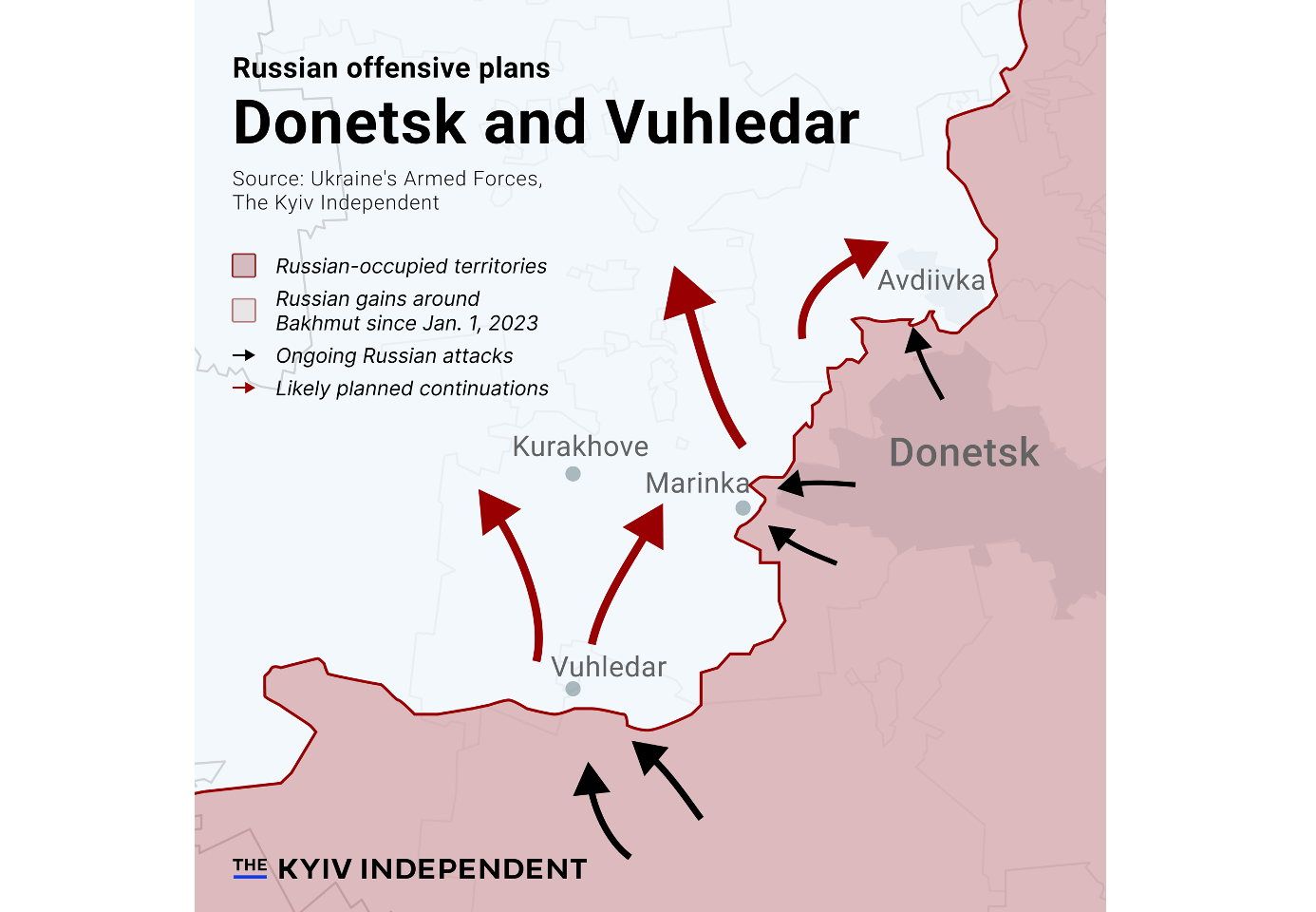

Starting in late January, large groups of Russian tanks and armored vehicles began advancing across snowy farmland just outside the front-line city of Vuhledar in the south of Donetsk Oblast.

At first, Russia’s defense ministry quickly announced progress in this sector – reports that soon proved to be out of touch with the reality on the ground.

Forced to cross vast areas of exposed terrain, Russian regular army units, filled out with mobilized recruits, were methodically churned up in an ultimately fruitless onslaught.

In scenes reminiscent of the first weeks of the full-scale invasion, advancing armor was eliminated in great numbers by a combination of Ukrainian artillery, anti-tank weaponry, and landmines.

One instance, captured by a Ukrainian drone, showed a column of three Russian infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) stopped in its tracks when the foremost vehicle struck a mine in the middle of a field.

In footage hard to believe until seen, the second IFV tries to pass its disabled comrades on one side, only to hit another mine, upon which the third tries the other side and quickly meets the same fate.

The attacks on Vuhledar were led by Russia’s elite 155th Naval Infantry Brigade, which earlier took part in the Battle of Kyiv. According to the U.K. Defense Ministry, the brigade has been “significantly degraded” in the disastrous attack, while The New York Times reported over 130 Russian tank and armored vehicle losses in the sector.

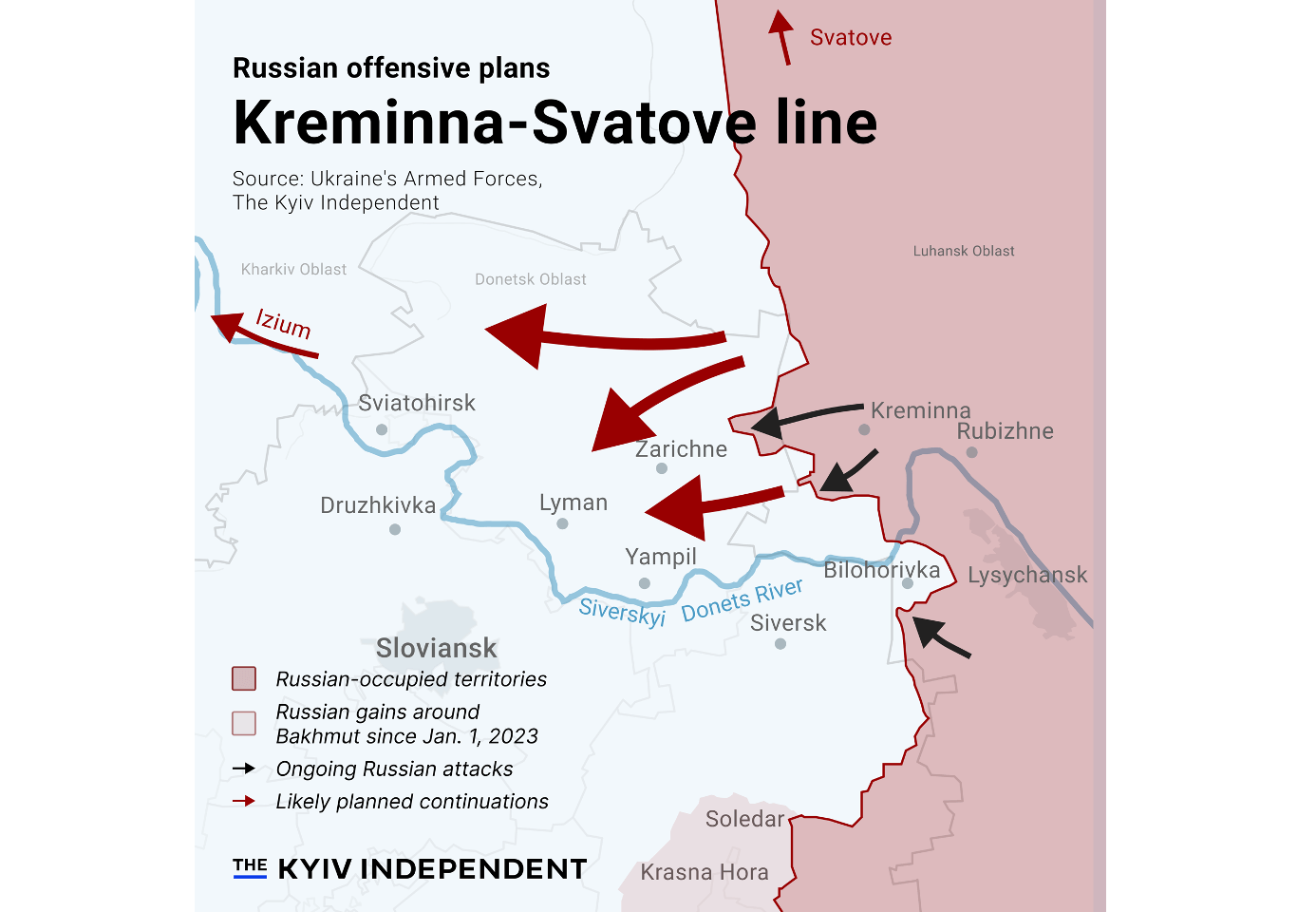

The other sector that has seen a flare-up of action has been in the deep pine forests near Kreminna, where the front line runs along the border of occupied Luhansk Oblast. Though Russia managed to make small gains in the area, Ukraine’s defense of liberated Lyman is holding firm.

Meanwhile, in the most brutal single battle of the war so far, Russian forces dominated by the notorious Wagner paramilitary group have slowly and steadily advanced on both flanks of the embattled city of Bakhmut.

After capturing the salt-mining town of Soledar, about 10 kilometers northeast of Bakhmut, in mid-January, Wagner forces have methodically closed their jaws around Bakhmut to the point that as of early March, no more sealed roads into the city remained under Ukrainian control.

Despite the city’s near-encirclement, Ukraine’s military, along with President Volodymyr Zelensky, has consistently confirmed its commitment to holding Bakhmut unless the situation significantly deteriorates further.

On March 5, the Institute for the Study of War reported that Ukraine was likely preparing a “limited tactical withdrawal” from the city, though it remained unclear if a total retreat could be expected soon.

Russia’s goals

Since Russian dictator Vladimir Putin announced the goals of the invasion as being aimed at the “demilitarization and denazification of Ukraine” on Feb. 24, 2022, the Kremlin’s publicly-stated aims have changed numerous times, often contradicting one another.

For a while, the aim was the “liberation of Donbas,” while in fact Russia was razing Donbas cities like Mariupol and Bakhmut to the ground.

This plan was made more confusing by Russia illegally laying claim to Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts in September, the capitals of which are now both firmly out of reach for Russian forces. Neither oblast is part of the Donbas.

Putin’s latest version, as explained to university students in Moscow in January, is even more nebulous: “the defense of (Russian) people and Russia itself from the threats that they (Ukraine and allies) are trying to create in our own historical territories adjacent to us.”

Vague formulations aside, Moscow likely no longer sees regime change in Kyiv or the complete capitulation of Ukraine as realistic, though state propaganda denying Ukrainian sovereignty has not slowed down.

Though Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi warned in December that Russia could again push to capture Kyiv from the north, a gathering of forces remotely capable of such an attack has failed to materialize.

Most observers understand the primary aim of Russia’s current offensive as the capture of the entirety of Donetsk Oblast, which has consistently seen the heaviest fighting of the war.

With this in mind, the capture of Bakhmut, costly as the fighting may have been, is a necessary stepping stone to then advance on the much larger cities of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, the central hubs of Ukraine’s operations in Donbas.

Meanwhile, breaking through in Vuhledar would open the gate to taking the west of Donetsk Oblast and threaten the right flank of Ukrainian forces defending Avdiivka near Russian-occupied Donetsk.

Russia’s potential success near Lyman would expose Sloviansk from the north and deliver a heavy morale blow to Ukraine, as the area was already occupied and liberated once.

Perhaps more important than the capture of territory is the attrition of Ukrainian forces.

Though Russian casualties in the months-long assault on Bakhmut are likely significantly higher than Ukraine’s, it is no coincidence that both sides have used the term “Bakhmut meat grinder” to describe the battle.

Ukrainian casualty figures are strictly classified, but it is known that Kyiv has tasked a significant portion of its available forces with the defense of Bakhmut.

Attrition of the enemy is a meaningful goal in itself, but the losses taken around Bakhmut are especially painful for Ukraine’s prospects at this crucial point in the war.

Speaking with the Kyiv Independent outside the city in early March, Ukrainian soldiers from multiple units reported being sent into battle without adequate training or support from artillery and armor.

Ukrainian units in this sector also include some of the army’s best-trained and most well-equipped brigades, seen as crucial for future offensive operations.

Nonetheless, experts believe that Russia’s choice to attack first defies military logic.

In conversations with the Kyiv Independent a few days before publication, renowned U.S. military experts Michael Kofman and Rob Lee shared their thoughts on the coming campaign after visits to front-line areas.

“To be honest, they (Russians) are probably doing the Ukrainian forces a really big favor right now,” said Kofman.

“The best thing Russian forces could have done is to launch an offensive with low likelihood of success, use up a lot of their artillery ammunition, and exhaust themselves.”

In the personalist dictatorship that is Putin’s Russia, a clear drive of territorial gains above all is observable in these attacks.

Having replaced the more cautious Sergei Surovikin as overall commander of Russian forces in Ukraine, General Staff chief Valerii Gerasimov is speculated to have been tasked with delivering an attacking victory to Putin.

“I think that Surovikin was more competent,” said Kofman, “his strategy was more focused on defense and force constitution, and his vision was likely to let Ukraine attack first in the spring.”

“Putin likely got impatient and Gerasimov thought they could attack now, but they don't have the force quality or the munitions to come out of this vulnerable period and have real offensive potential.”

Tactical challenges

Even if Russia boasts a large advantage in numbers and artillery, assaulting prepared, multi-layered defensive lines pose a huge challenge for any attacking force.

Each of the three main axes of Russia’s offensive presents a different tactical challenge.

The most difficult terrain to attack on are the open fields of Vuhledar, while the thick forest near Kreminna makes concealment easier, but maneuver more difficult.

Around Bakhmut, Wagner has used tens of thousands of mercenaries, mostly from Russia’s prison system, to effectively advance through dense urban terrain without regard for human casualties.

The brutal effectiveness of this approach was apparent when the Kyiv Independent observed Wagner’s assaults with an elite Ukrainian drone unit on the outskirts of the city in late December.

Covered by mortar and grenade launcher fire, small teams of Wagner troops would pick their way through the churned-up landscape towards Ukrainian lines.

If spotted and targeted early enough, they could be engaged by Ukraine’s artillery, but often by the time they were noticed, the assault group would be right on top of a Ukrainian-held trench.

Wagner’s methods have given Russia its first territorial gains since summer last year, but Moscow knows it cannot attack in the same way in other areas of the front line.

“Because Wagner's using prisoners,” said Lee. “I don't think mobilized troops can replicate Wagner, which is allowed to operate by different rules.”

Unlike Wagner, the regular Russian army units attacking in these areas, having lost much of their professional soldier and officer core in the early months of the war, are now padded with tens of thousands of mobilized troops.

According to Kofman, Russia’s initial wave of mobilization has already been largely spent, part of which was sent straight to the front without training in the late autumn, the rest of which has filled out Russian brigades after a little more preparation.

“There isn't a second Russian army of another 150,000 troops on the horizon,” he said.

Can Ukraine strike back?

Russia may have shown its hand regarding its offensive potential, but the greater unknown is Ukraine’s ability to make its own breakthroughs in the spring.

Ukraine achieved stunning counteroffensive victories in autumn last year, most notably in September when Ukrainian units broke through a weak spot in Russian lines and routed Russian forces from almost all of occupied parts of Kharkiv Oblast.

The liberation of Kherson Oblast on the western bank of the Dnipro River in November was also significant for Ukraine, but was made much easier by the logistical advantage posed by the river behind Russian forces.

Since autumn, the going has been much tougher.

Hardened Russian units have been freed up from the defense of occupied Kherson, while the injection of mobilized troops make it harder for Ukraine to find poorly manned sectors to exploit like in Kharkiv Oblast.

For two months after Ukrainian forces liberated Lyman in Donetsk Oblast in early October, the world watched as they attempted to break through the next line of Russian defenses between Kreminna and Svatove into occupied Luhansk Oblast.

Now, it is Russia that is once again attacking in this sector.

“One of the big problems is that both the Ukrainian and Russian militaries are mobilized armies,” said Lee.

“It's easier to train someone to stand in a trench and defend and shoot someone coming at them, but it's much more difficult to train them to do offensive operations.”

“It takes a lot more courage and unit cohesion; it takes better leadership and command and control,” he added.

Though lacking in quality, Russian forces have been able to leverage overwhelming advantage in manpower and artillery shells.

With much higher value placed on equipment, ammunition, and the lives of its soldiers, Ukraine is objectively not able to attack in the same way.

Hard and costly as it may be, mounting a large offensive in the first half of 2023 is also seen as a political imperative for Ukraine, whose leaders have pledged to liberate all territories occupied both before and after Feb. 24, 2022.

“In order to do that,” said Lee, “Ukraine needs to achieve another Kharkiv-type operation, where they can really rapidly progress in one direction and try to collapse Russian lines, and exploit it in a way that makes it difficult for Russia to reconsolidate.”

As for where such an offensive might take place, there is one direction that has dominated the discussion for good reason.

“It's clear that a decisive offensive is something that's only going to happen in the south,” said Kofman, “it’s clear to anyone who takes a glance at the map.”

A large-scale thrust south into the partially-occupied southeastern Zaporizhzhia Oblast, taking the key transport hub of Melitopol and potentially reaching the coast of the Azov Sea, would not only cut off Russia’s coveted “land bridge” to occupied Crimea, but would also allow Ukraine to strike the Crimean Bridge and isolate Russia’s foothold on the peninsula.

Crucial will be Ukraine’s ability to first degrade and exhaust Russian forces while on the defensive, at minimal cost to their own units.

“Every time Russia is getting into fights like in Vuhledar where they are taking heavy casualties and Ukraine is not, that is a good thing,” said Lee.

“Because then, Ukraine might find a part of the front lines where Russia is weak and they can't defend properly.”

“Ukraine needs a lot more Vuhledars and a lot fewer Bakhmuts,” Kofman added.

Kyiv is making no attempt to hide its preparations. As it gradually receives more Western tanks and IFVs over the spring, Ukraine is forming a new force auspiciously named the Offensive Guard, consisting of eight specialized assault brigades coordinated by the National Guard.

When the time comes to launch the attack, Ukraine will need everything to go right, according to Lee.

“It's difficult,” he said. “It doesn't mean Ukraine can't succeed, but they have to be very smart about finding the weakest point in Russian lines, do the best shaping operations beforehand, having the best units, the best NATO-standard mission command decision-making.”

Setting the tone

Despite the scale of destruction that Ukraine saw in the first year of the all-out war, both sides’ offensive ambitions mean that 2023 could be even bloodier.

Already, Russian casualty rates as reported by Ukraine’s General Staff over 2023 have been consistently the highest of the full-scale war.

Ukraine’s count of estimated Russian personnel losses passed 100,000 on Dec. 22, last year, 301 days after Moscow launched its full-scale invasion on Feb. 24.

That same figure reached 150,000 on March 2, only 71 days later.

On March 5, Ukrainian military intelligence chief Kyrylo Budanov said that Russia would “run out of military tools” i.e. offensive potential, by the end of spring.

Russia’s performance in its latest offensive looks so far to back this up, but after it culminates, all eyes will be on Ukraine’s.

With Russian artillery fire still outweighing that of Ukraine, and talk of China potentially taking the plunge and supplying munitions to Moscow, experts agree that a long, attritional fight will only work in Russia’s favor.

Whatever the result, it is more than likely that the spring campaign will decide whether the war will lurch towards total Ukrainian victory, or slowly begin to freeze.

“I think Ukraine will have success,” said Lee, “but the question is how much.”

“It’s going to be difficult to achieve, but the one thing we've seen in this war is the Ukrainians do pretty remarkable things.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Francis Farrell, cheers for reading this article. I grew up on the other side of the world, but in Ukraine I have found a home unlike any other. Just like with so many of our readers, I understand that you don't have to be from near here to realize how important Ukraine's struggle is for freedom and human rights all over the world. The Kyiv Independent's mission is to lead the way in continuing to bring the best homegrown, English-language coverage of this war, even if the rest of the world's attention starts to fade. Please consider supporting our reporting.