A year into full-scale invasion, West struggles to seize Russian assets for Ukraine

Hundreds of potential international investors met with top Ukrainian and Western officials in London in late June to discuss how to rebuild the country, ravaged by Russia’s war.

Those attending the Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC) were unanimous — Russia should foot the bill.

Said bill is devastatingly large. Ukraine needs at least $411 billion for its recovery, a World Bank report stated in March.

That was before Russia blew up the Kakhovka dam on June 6, unleashing a humanitarian and ecological catastrophe in southern Ukraine.

Every day, the costs of reconstruction rise as Russia continues to kill civilians and destroy infrastructure, and sanctions packages may not be enough to bring in compensation.

So far, the U.S. and its allies have reportedly frozen $58 billion worth of Russian oligarchs’ assets, including 24 billion euros ($26 billion) in Europe.

The EU also announced the freezing of 200 billion euros ($215 billion) worth of Russia’s Central Banks’ assets abroad as of May 25.

Yet, the unanimity stops at seizing these funds, that together account to over $270 billion.

More than a year after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and Europe’s promise to crack down on Russian money fuelling Putin’s war machine, Western countries still fall short of adequate solutions to use frozen Russian funds to rebuild Ukraine.

The EU is still looking for a solution to confiscate the funds without infringing its own rule of law.

The Russian assets in Europe are a drop in the ocean, Oliver Bullough, a UK journalist and author who has extensively covered corruption and former Soviet Union oligarchs, told the Kyiv Independent.

“If this wealth can be confiscated, it's going to take years,” he said. “And if it is confiscated, what's confiscated won't be nearly enough to rebuild Ukraine.”

Legal hurdle over Russian Central Bank

The EU faces a legal dilemma: it can’t legally confiscate frozen Russian assets without infringing on legal property.

Christian Wigand, the EU Commission spokesperson, was adamant about respecting the rule of law.

“We need to respect the rule of law and judicial independence because we cannot do the same things that those states that attack our values,” Wigand said.

“The gut feeling would probably be to say, let's just take this money into Ukraine,” he said.

Yet, the EU can't just confiscate the Russian Central Bank assets. Its reserves are protected by Russian sovereign immunity, which makes it impossible to seize without twisting international law.

Instead, the EU is working on putting these assets to work, which means using the interests created by these assets without seizing them.

“What you can do is to work with the interests that you can create, it's money and quite a big sum,” Wigand said.

According to an EU document obtained by Bloomberg, the frozen funds generated nearly 750 million euros in interest between January-March this year.

Bullough said the other option was to follow the example of Canada “and pass legislation that just makes it easier to confiscate wealth.”

“That's not very popular in Europe, but that is the other option.”

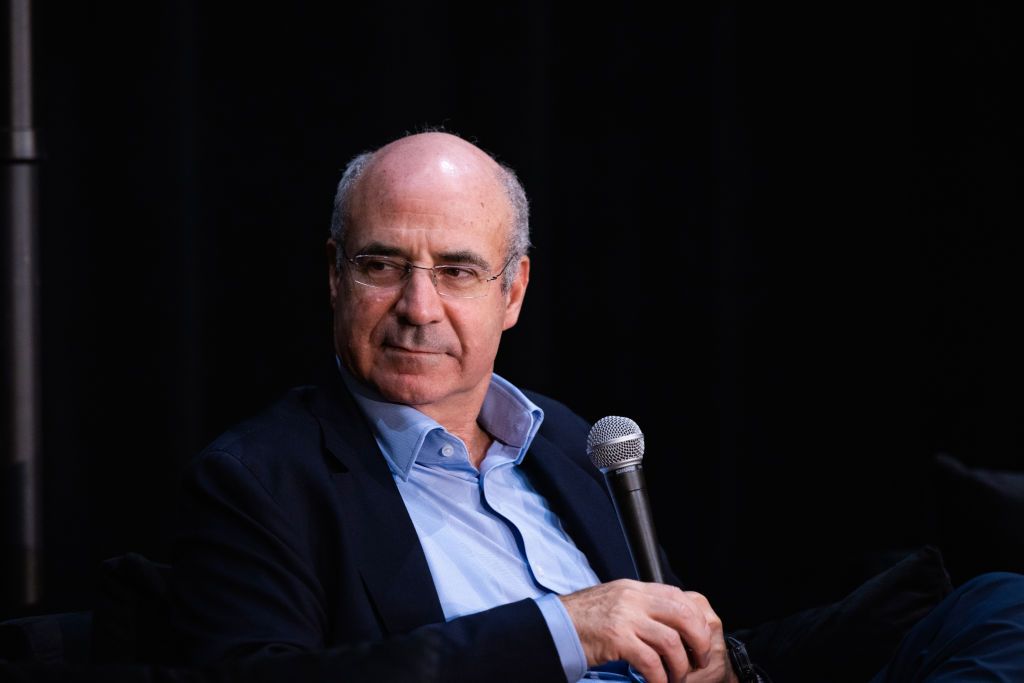

In an interview with the Kyiv Independent, London-based American investor Bill Browder said laws must be rewritten “to say that sovereign immunity, of course, always applies, except if a country is guilty of an act of aggression against a peaceful neighbor, in which case, the damages caused by that crime of aggression, should trump sovereign immunity.”

“It's not a legal issue, it's a political and moral issue.”

Confiscating oligarchs’ money

So far, assets worth 24 billion euros belonging to 1,470 sanctioned oligarchs and 200 legal entities have been frozen in Europe. But to seize them, Western countries must prove that this money is tied to criminal activities.

While sanctions can be used as a foreign policy tool to exert pressure, confiscation falls under a completely different category, Maria Nizzero, a Research Fellow at the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies at UK’s Royal United Services Institute, said.

“When we talk about confiscation, we are talking about expropriating the property of somebody of an individual that, regardless of who we're talking about, is still an individual,” she told the Kyiv Independent.

“And because of that, that's a criminal justice matter, and therefore, a different type of law, which is the proceeds of criminal activity, needs to come into place.”

“Obviously, it feels normal to say, ‘Russia is committing atrocities in Ukraine, the oligarchs have been supporting the Kremlin, so why don't we go for it?’” Nizzero said.

“We're talking about applying something that can be used as a precedent for other cases,” referring to using confiscation to destroy political opponents in authoritarian regimes.

In short, one must prove that Russian funds are dirty to seize them, and it’s a daunting task when faced with the countless shell companies oligarchs use to evade sanctions.

Oligarchs often use a maze of shell companies, offshore trusts, and an army of lawyers to hide the dubious origin of their ill-gotten fortune.

“Russian oligarchs have been stealing and hiding this money for 30 years,” Bullough said.

“They have the best lawyers, the best accountants, the best offshore service advisors helping them, you can't unwind that in a year.”

Nizzero echoed Bullough’s statement, advocating for more support for law enforcement to build their cases.

“Law enforcement still probably does not have the tools to do it,” she said. “It's not that oligarchs have stopped doing what they were doing.”

Yet, ahead of the London conference, the UK unveiled legislation on June 19 to keep sanctioned assets frozen until Moscow has agreed to pay compensation to Ukraine.

The new measures require any individual designated under the sanctions to disclose assets held in Britain, as well as a new route for frozen assets to be donated to the reconstruction of Ukraine without resulting in individual sanctions being lifted.

However, according to Nizzero, the focus should be on Russia’s Central Bank’s assets and state assets in general rather than on oligarchs, which represent “such a tiny, tiny fraction of what's needed for Ukraine.”

Enforcing the law

The U.S., Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the European Commission launched the Russian Elites, Proxies and Oligarchs (REPO) Task Force in March 2022 to crack down on Russian assets abroad.

The REPO task force coordinates between law enforcement of each country and closely works with Europol and Eurojust to track down dirty Russian money.

But investigating and tracking Russian money is different than indicting someone, Bullough said.

Sanctions just freeze assets, and implementing them depends on local authorities' “level of enthusiasm” to apply them — which is a different story when an entire nation has been using dubious Russian funds as a piggy bank for decades.

Seizing Russian money implies having proper regulation and law enforcement ready to do so, Bullough said.

“The big distinction between the U.S. and the rest is that the U.S. has the law enforcement muscle to move from freezing to seizing in a way that none of the other countries do,” he said.

The U.S. amended laws to make it possible to seize Russian assets and hand them to Ukraine in December 2022, but it only applies to assets confiscated for violating American sanctions.

Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev was on the top of the list, which made him the first target of the U.S. policy on May 11, when Attorney General Merrick Garland authorized the transfer of forfeited Russian assets to Ukraine for the first time.

“While this represents the United States’ first transfer of forfeited Russian funds for the rebuilding of Ukraine, it will not be the last,” Garland said, as quoted by Reuters.

In 2014, the U.S. and EU blacklisted Malofeev, founder of Russia’s propaganda outlet Tsargrad TV, for financing Russian-backed proxies in eastern Ukraine.

In February, after meeting with Ukraine’s Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin, Garland authorized using $5.4 million in confiscated assets.

In comparison, the EU is still lagging behind, while trying to sort out the legal hurdle of confiscating Russian assets.

In May 2022, the European Commission suggested that oligarchs should be punished for circumventing sanctions by having their frozen assets confiscated, but the bloc doesn’t have those measures.

The procedural review of this proposal is ongoing.

“So unless we start seeing major investment in law enforcement by the other, particularly the European countries, it's hard to see that anything substantive will change,” Bullough said.

Usual suspects

Western allies must also track down Russian assets to evaluate their actual worth.

The estimate that there are 300 billion euros in blocked assets, announced in October 2022, was only based on the statements of Russia itself, a massive discrepancy worth 100 billion euros.

Yet, reports of frozen Russian money are taking pace, Wigand said, while admitting there is still much to do.

“We see momentum, but there is still some homework for some member states,” he said, without specifying which ones.

EU member states must report these figures to the task force, however low they might be.

And some EU countries have reported significantly low amounts compared to what their central banks received.

“It's the usual suspects,” Bullough said. “It's Cyprus, for example.”

Cyprus has long been considered a tax haven for dirty money due to its opaque financial system and permissive local courts, attracting scores of shell companies to hide money laundering.

On May 4, the EU's Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders said Cyprus’ reported sum seemed to be “a little low” after the island-nation reported freezing only 100 million euros ($110 million) worth of assets.

Reynders reportedly cited the Cyprus Central Bank saying the country had received 96 billion euros in Russian investments in 2020 alone.

The Cypriot Finance Minister soon announced on May 16 that some 1.2 billion euros ($1.3 billion) in Russian-owned assets managed by Cyprus-registered companies had been frozen in compliance with sanctions, Associated Press reported.

Malta also stands out as one of the most reluctant to disclose and freeze Russian assets among EU members.

Reynders expressed “surprise” on April 27 that Malta had only frozen some 220,000 euros in Russian-owned assets.

Greece also confirmed it had notified the bloc of freezing assets worth 212,000 euros, according to a document seen by Reuters in January.

"Either they don't have much, or they are not doing their job,” an undisclosed EU official also told Reuters. “Or they have done something but not communicated to us even though they had chances."

Such a lack of transparency is not surprising for Nizzero.

“I wouldn't be surprised if they found the proceeds of criminal activities because historically speaking, (Malta and Cyprus) have facilitated and attracted a lot of investment from murky origins.”

“And that’s without accounting for countries that don’t apply Western sanctions, such as Turkey and the United Arab Emirates,” Bullough said.

It has been relatively easy for Russians to divert their business interests elsewhere, according to Bullough.

The situation is particularly problematic because Turkey sells citizenship, so it's not difficult to get a new identity via Turkey and carry on as before, which makes it even more challenging to put a hand on Russian assets.

“We just have to hope that governments retain their focus on this, you know, on this issue because don't get distracted by other things,” Bullough said.

“I think all of the easy achievements have been done,” he said. “And what's ahead is the real hard work, to be honest.”

Editor's Note: In an email statement to the Kyiv Independent, a spokesperson for Oleg Deripaska denied he was an oligarch, claiming “he never acquired any assets from the state,” his involvement in politics, and his alleged proximity with Russian dictator Vladimir Putin.

Deripaska built an aluminium, energy and industrial empire from previously state-owned assets privatized after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, with the help of another oligarch, Roman Abramovich.

In 2020, the Office of Foreign Assets Control, the agency overseeing U.S. sanctions policy, wrote to Deripaska’s lawyers that he was “reportedly identified as one of the individuals holding assets and laundering funds on behalf of Russian President Vladimir Putin” in 2016, an alleged collusion Deripaska also denied at the time.”

Note from the author:

Hello, this is Alexander Query, the author of this explainer; thank you for reading this piece. The road to getting Russian reparations to rebuild Ukraine is long and arduous, but hope dies last.

As Ukraine keeps fighting for justice, we, at the Kyiv Independent, take pride in reporting every step of the way from the ground — but we do need support from our readers to keep us going.

Let us be your eyes and ears by donating or becoming our member.