AI drones in Ukraine — this is where we're at

Artificial intelligence is running up against hardware barriers in rendering Ukraine’s drone swarms autonomous.

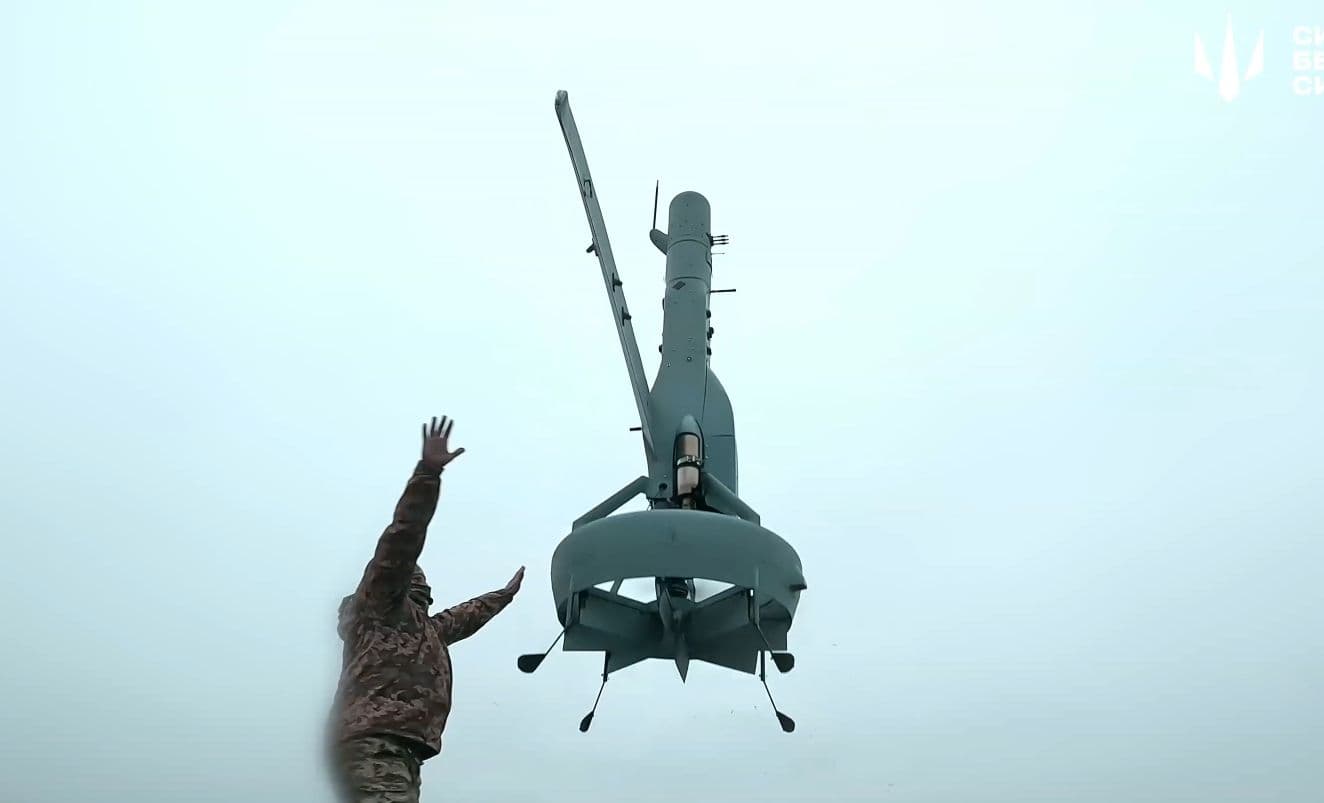

A V-Bat drone used by Ukrainian soldier in an undisclosed location, Ukraine in February 2025. (The Unmanned Systems Forces / Militarnyi)

Ukraine’s drones are setting new standards for self-piloting on the battlefield. Full autonomy, however, remains well out of reach — and is likely to stay there.

The broader vision of drones operating fully independently of pilots remains something of a holy grail for drone developers, even as it may seem a dystopian nightmare to many human rights activists and luminaries, including the pope himself.

Ukrainian developers hope that progressively delegating more tasks to drones and software can free up pilots and their attention spans, which, in turn, can compensate for the lack of manpower relative to Russia, which is typically pegged at a ratio of about 3-to-1.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is often mentioned alongside autonomy to the point that in Ukrainian weapons circles, the terms are often used interchangeably. But AI technologies and their underlying neural networks remain far from capable of making choices on the Ukrainian battlefield.

“We’re not going along the route of that full autonomy,” Andriy Chulyk, a co-founder of Sine Engineering, which makes drone guidance modules and software, told the Kyiv Independent. “Tesla, for example, having enormous, colossal resources, has been working on self-driving for ten years and — unfortunately — they still haven’t made a product that a person can be sure of.”

Beyond the moral hazards of giving any computer a license to kill, drones face a major barrier in terms of what they can carry.

When it comes to consumer-facing AI applications like ChatGPT, cloud computing hides AI’s insatiable appetite for computing power in distant data centers. In contrast, drone autonomy is most useful precisely in situations where data connections with operators and, by extension, potential cloud linkage die. Delegating life-or-death decision-making to the kind of computer a 10-inch drone can carry remains a distant prospect.

“(AI) is in use virtually everywhere, but you have to take into account that it can make mistakes,” as Ukraine’s Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi told RBC-Ukraine in August. “Virtually all of our technological weapons have elements of artificial intelligence.”

“The main role of AI in the nearest future on the real battlefield will be just a kind of supportive function rather than replacing humans,” Kate Bondar, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the Kyiv Independent.

Smarter Shahed-type drone interceptors

One of the most promising of these applications is in interceptor drones, which aim to strike down fast-moving Russian Shahed-type drones as they criss-cross Ukraine.

Given Ukraine’s size and the speed of newer jet-powered Shaheds, interceptors need to be ready across a vast territory, while taking as few operators as possible.

“It's just execution, where AI can be way, way more efficient than a human, because the Russians are installing these avoidance systems, and they're starting to maneuver, and it's in the air, so it will be easier for software to react on that, to adjust the flight of the interceptor, rather than relying on connection, latency, and taking into account all the factors that operator cannot feel, like wind gusts, et cetera, et cetera.”

Interceptors “still rely on FPV technology,” Yaroslav Azhnyuk, founder and CEO of two companies, the Fourth Law and Odd Systems, told the Kyiv Independent. Odd Systems started off as a mass FPV producer, though it’s currently testing anti-Shahed-type drone interceptors. The Fourth Law, meanwhile, produces small and cheap — roughly $70 — AI vision modules for FPVs.

“The difference between most Ukrainian interceptors and, say, Merops produced by Eric Schmidt’s company, is that Ukrainian solutions currently lack the AI part of it.”

Supercharged FPVs

When it comes to FPVs, AI is fairly standard issue, largely in the form of “last-mile targeting,” which allows a pilot to select whatever object on the screen they want the drone to head towards — maybe a soldier, maybe a bunker, maybe an S-300 — while they still have a video linkage. The drone will retain and zoom towards the visual target its pilot clicked on even after the connection to the pilot falters due to electronic interference.

Last-mile targeting in Ukraine’s FPV drones was a big step in circumventing Russian radio-frequency jammers, but it has remained the province of fairly simple machine vision software for over a year. Last-mile targeting also requires a pilot to select and lock on a target in a way similar to the predictive focus tracking found on any decent DSLR camera for years. In other words, it’s not exactly a technological revolution.

Azhnyuk has not given up on full autonomy as a way of multiplying Ukrainian FPV forces “by a factor of 100.” But for the time being, the Fourth Law’s impact has been primarily in streamlining the necessary neural networks to, for example, hold last-mile targeting even on Russian vehicles driving through shadows or soldiers hiding in tree cover.

He touts preliminary results of one brigade using his products, which he said have boosted the rate at which drones hit their end targets from 20% to 80%. Among the biggest changes in his AI is the ability to recognize a target as it passes through shadows or treelines, rather than locking on to a set of pixels that such distortions to the visual field camouflage.

Speaking with the Kyiv Independent, Azhnyuk says that full autonomy in one-off demos would already be feasible, but “massive deployment” is a whole different challenge, one that’s nowhere in sight.

Striking deep

Among the most obvious use cases for autonomy in drones is missions that go far beyond the distance at which a drone can maintain radio contact with its operator — particularly with cheaper kamikaze drones on which it’s not worth mounting, for example, a Starlink.

Deep strikes, however, are an illustrative example, as there is no chance Ukraine will let its deep-strike drones do their own target selection any time soon. They spend too much time flying over Russian cities and civilians to be left up to their own devices — or target selection.

A recent partnership between US-originated Shield AI and Ukrainian Iron Belly is illustrative of the future.

In a training field in Western Ukraine, a V-BAT — a million-dollar reconnaissance drone with a sticker loitering time of 13 hours — takes off in the direction of a practice target, in this case a civilian car.

The V-BAT returns with a trail of images taken along the way, and pictures of the target itself from every angle. It passes these along to the D4, a cheap kamikaze drone that uses onboard AI software and its own camera to track those images back to the target in question

A light rain picks up shortly after the D4 launches, blurring its camera and sending it off course for some 20 minutes. The operators, however, let it ride out the weather without touching its controls. It eventually self-corrects, making some demonstrative swoops of victory over the target car when it arrives.

Such deployment of AI would effectively extend the range of “last-mile targeting” to a hundred kilometers or more. It remains, however, in the testing phases.

Does not compute

The U.S.-made V-BAT is armed with top-of-the-line camera equipment that rarely makes it to Ukraine, largely due to the cost.. Part of the issue, Bondar says, is that while Ukrainian drones have accumulated enormous visual data since February 2022, the origin of that data is “mostly analog, cheap cameras.”

“Yes, it will be able to distinguish between a tank and a human. It will identify that it's a tank or it's a vehicle or that it’s a human. But not more than that. So the problem of, for example, distinguishing between a Russian and Ukrainian soldier, or even a soldier and a civilian, has not been solved,” said Bondar.

The software powering much of Ukraine’s visual AI is heavy on open sourcing. While free software like YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once) is economical, it’s unlikely to be the best in the world.

Bondar, for one, is suspicious that much of the AI talk in Ukrainian drones is driven by marketing.

“War’s also a business. You have to sell something, you have to be competitive, and to be competitive you have to have an advantage. To have AI-enabled software, or some cool AI system, that's something that sounds really cool and sexy,” Bondar said.