In the early 19th century, one of the founding fathers of modern war studies, the Prussian general and military historian Carl von Clausewitz, commented on the Napoleonic Wars: "The conqueror is always peace-loving; he would much prefer to march into our state calmly."

This remains an observation that applies to most military aggressions.

Yet, Clausewitz's basic idea was ignored by most Europeans in their interpretation of Moscow's behaviour after the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014.

Much of European diplomacy and commentary until 2022 instead built on the assumption that the Kremlin's public insistence on the peacefulness of its intentions towards Kyiv implies that one can and should negotiate and moderate Russian aims and behaviour in Ukraine.

This inapt premise ignored that Russian President Vladimir Putin merely preferred Ukraine's non-violent takeover to an uncertain future military campaign against Kyiv. When, eleven years ago, Russia annexed Ukraine's Crimea and covertly invaded eastern Ukraine, the war as such had no benefits for Putin and his entourage.

Instead, a hybrid subversion of Ukraine by Russian agents and proxy forces, rather than a violent occupation of most of the Ukrainian lands by tens of thousands of regular Russian troops, was the preferred method.

During the last three years, however, the role of Russia's - now full-scale - military invasion of Ukraine for Putin's regime has changed. One the one side, the war itself has acquired a stabilizing function for the Russian political system that relies on an increasingly extremist ideology, militarized economy and mobilized society. On the other side, most European politicians, diplomats and experts now have fewer illusions about Putin's putative love for peace than they had a decade ago.

In contrast, the hitherto largely adequate perception of Moscow's strategy in Washington has been replaced, since January 2025, by an escapist approach to the Russo-Ukrainian War.

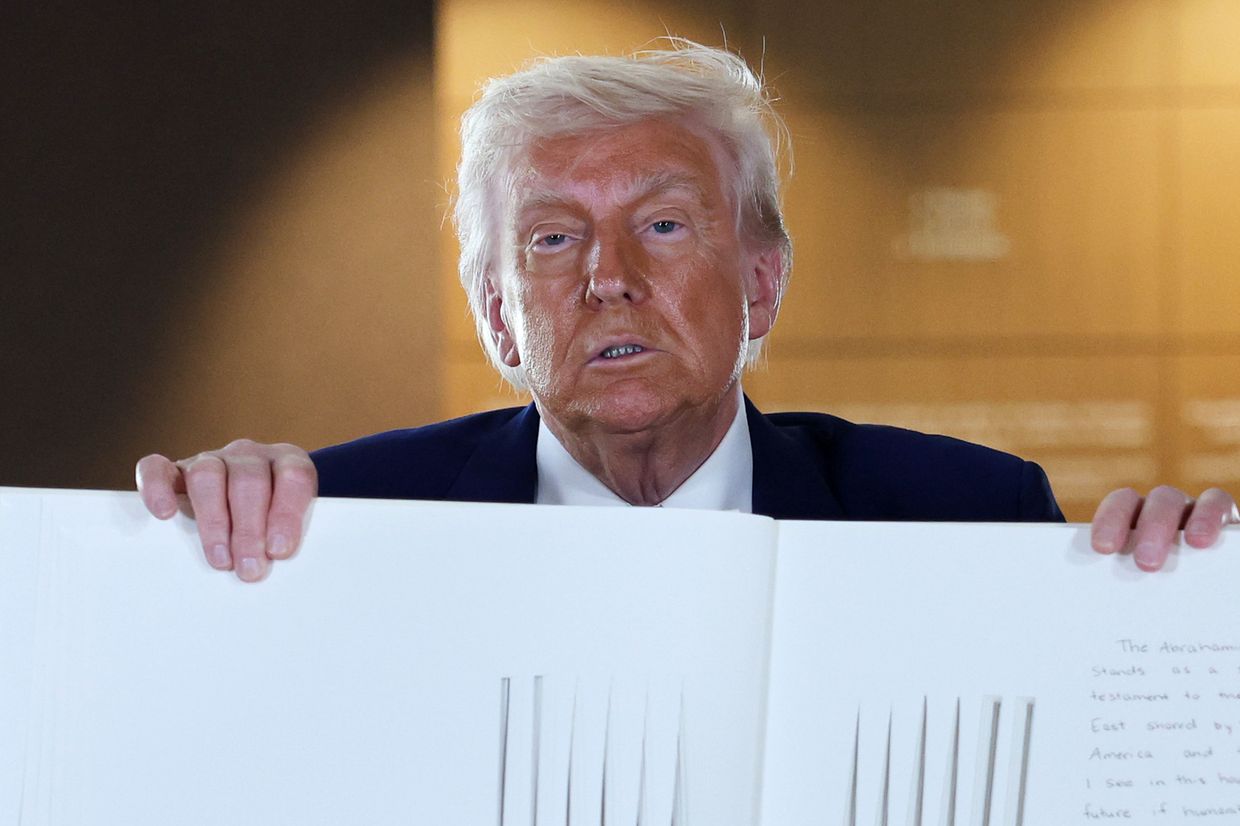

The degree of the new U.S. administration's political naivety, moral indifference and diplomatic dilettantism, during its first four months in office, has been astonishing. Even in view of the aberrations during Trump's first presidency of 2017-2021, the inadequacy of the last months' statements and actions by the White House regarding the Russo-Ukrainian War has triggered shockwaves in Europe and elsewhere.

One suspects that not only strategic infantilism, but also political respect and even personal sympathy, in the Trump administration, for Putin, have been driving the recent zigzags of the U.S.

Four months of American shuttle diplomacy and mediation attempts have achieved only little. The results of this week's two-hour conversation between Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump have also been meagre. To be sure, the two presidents spoke, after their telephone talk, of success.

Yet, there are no tangible outcomes of the intense trilateral negotiations between Washington, Moscow, and Kyiv, and of the direct interactions between the U.S. and Russian presidents.

Putin made it clear that there would not be any ceasefire soon.

Russian imperialism will not be neutralized by negotiations, compromises, or concessions.

Trump announced that there should be direct negotiations between Russia and Ukraine, as if the two countries had not been negotiating with each other, in different formats, for more than eleven years already.

In his comment about Monday's phone call, Putin, in fact, engaged in a trolling of Ukraine, the U.S., and the entire West in two ways.

First, the term that Russia has recently introduced and Putin used to label the primary aim to be achieved in upcoming negotiations is "memorandum." Everybody familiar with the history of post-Soviet Russo-Ukrainian relations will know that there exists already a historic security-related "memorandum" signed by Moscow and Kyiv (as well as Washington and London) at Hungary's capital more than 30 years ago.

In the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, Moscow guaranteed, in exchange for Kyiv's agreement to hand over all of its nuclear warheads to Russia, that it would not attack Ukraine. Washington and London too assured Kyiv that they respect the Ukrainian borders and sovereignty.

After Moscow has been demonstratively trampling the letter and spirit of the Budapest Memorandum for eleven years, the Kremlin is now offering to sign another Russo-Ukrainian "memorandum."

Second, Putin did not exclude, after speaking to Trump, that future negotiations with Kyiv may lead to a truce. Yet, the Russian president added that, "if appropriate agreements are reached," a "possible ceasefire" would only be "for a certain period of time." Even if the negotiations are successful, the armistice will be merely temporary.

That caveat by Putin is an apt admission: The Russian war economy and population's military mobilization are now so far advanced that they cannot be easily stopped. Moscow is not any longer able to abruptly discontinue warfighting. What would happen to Russia's hundreds of thousands of enlisted soldiers, large-scale weapons production, and routine bellicose as well as intense Ukrainophobic campaigns in many spheres of Russian social life (education, media, culture etc.), if there is suddenly a permanent peace?

These and similar signals from Moscow allow only one conclusion: To end the Russo-Ukrainian War, Russia needs to experience a humiliating defeat on the battlefield.

The lesson from the past is, moreover, that Russian military failures have triggered domestic liberalization, such as the Great Reforms after the Crimean War of 1854-1856, or the introduction of semi-constitutionalism following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.

One of the determinants of Glasnost and Perestroika was the disastrous failure of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979-1989.

Russian imperialism will not be neutralized by negotiations, compromises, or concessions. Instead, such approaches only promote further foreign adventurism in Moscow and military escalation along Russia's borders. The Kremlin will one day end Russia's expansionist wars as well as genocidal terror against civilians in Ukraine and elsewhere. Yet for that to happen, the Russian people first need to start believing that such behaviour cannot lead to victory, may trigger internal collapse, and will be resolutely punished.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.