New book exposes Russia’s ecocide as a war against Ukraine’s land – and memory

When Russia destroyed Ukraine’s Kakhovka Hydroelectric Dam in June 2023, unleashing catastrophic floods across the country’s south, it seemed like such a blatant act of environmental and humanitarian devastation might finally jolt the international community into taking more action to support Ukraine.

But two years later, that flashpoint has dimmed, buried beneath a grim and growing list of atrocities that have followed in its wake.

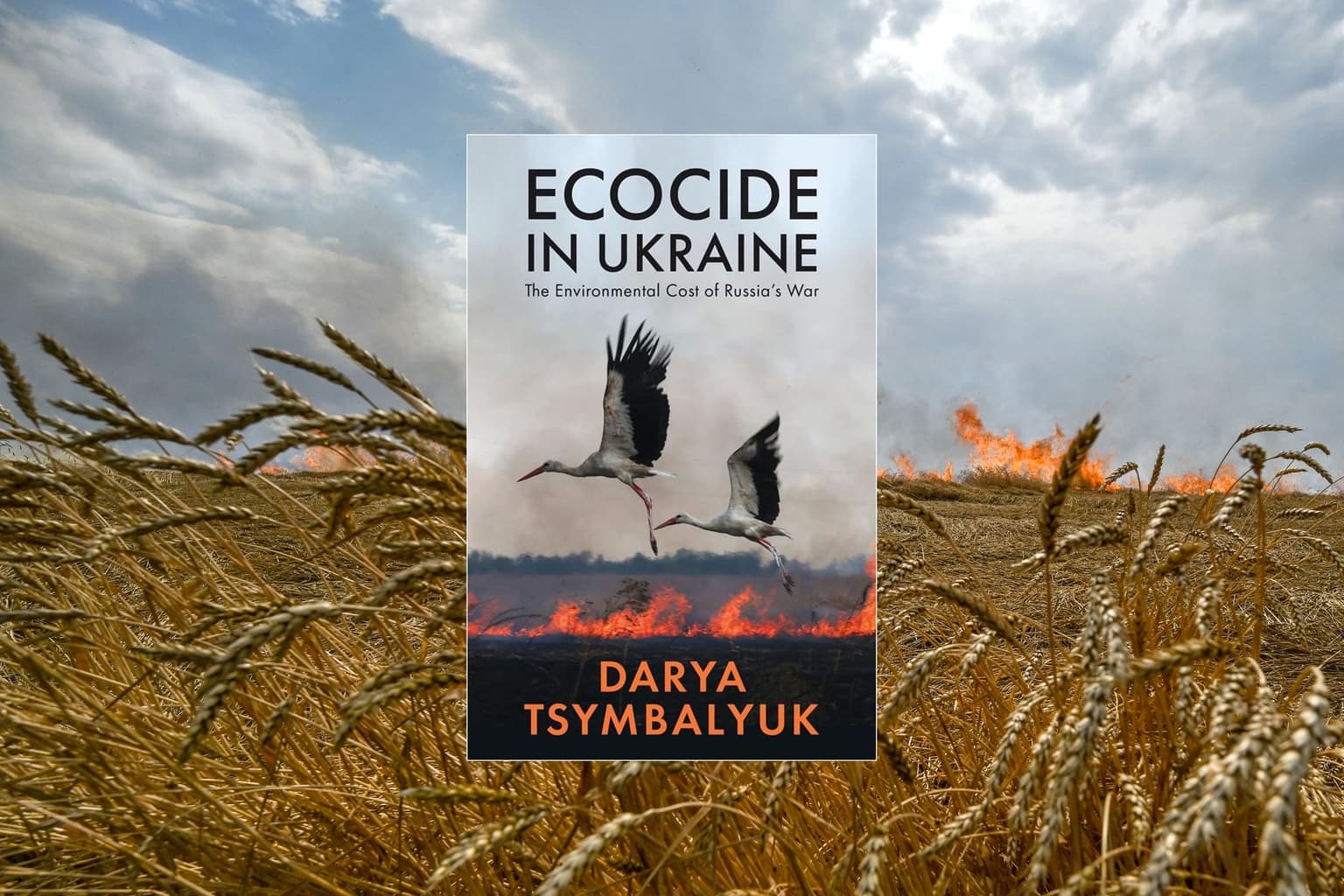

In the book “Ecocide in Ukraine,” Ukrainian scholar Darya Tsymbalyuk places the destruction of the Kakhovka dam at the center of a broader look into Russia’s ongoing environmental destruction of Ukrainian land.

The book explores how deliberate ecological devastation has not only caused immediate harm to landscapes, communities, and ecosystems, but also threatens to sever Ukrainians’ deep-rooted cultural connections to the land. Drawing on her southern Ukrainian roots, Tsymbalyuk blends personal insight with scholarly rigor, giving the book an understated yet powerful emotional resonance.

From age-old folk traditions like Zeleni Sviata and Ivana Kupala that honor nature and the fertility of the land to enduring customs of consuming seasonal, locally-grown produce, much of Ukraine’s cultural identity is rooted in nature. This connection is not only symbolic but practical: the country’s rich soil, known as “chornozem,” is one of the reasons it is among the world’s leading exporters of wheat, sunflower oil, and oilseeds.

It's difficult to understate the scope of damage caused by Russia's ecocide against Ukraine. Events like the flooding of Ukraine’s south not only caused a number of casualties and destroyed countless people’s homes — it reshaped the geographic landscape for generations to come.

Statistical data on the ecocidal damage inflicted by Russia upon Ukraine risks overwhelming the reader — what does at least 5,000 square kilometers of wildlife impact mean to the average reader located on the other side of the world? However, Tsymbalyuk presents this data alongside testimonies from the disaster of Kahkhova, stirring up powerful emotions that the numbers alone might not have captured.

Beyond the more visible acts of ecocide committed by Russia against Ukraine are quieter, less conspicuous losses that are no less tragic. In her book, for example, Tsymbalyuk references the tradition of mushroom picking. Long a cherished ritual for Ukrainian families, the practice is now fraught with danger in parts of the country’s north, east, and south, as landmines litter the forests.

As Tsymbalyuk explains, what’s been lost is more than just a seasonal pastime for Ukrainian families and friends. Mushroom picking was a way of familiarizing oneself with the land and of passing down such wisdom through generations. Without it, Ukrainians are not just losing a tradition — they are losing a connection to the land itself, a subtle but profound unmooring.

Russia’s ongoing ecocide against Ukraine is also a growing threat to global food security — among the most iconic and harrowing images of the war are those of Ukraine’s burning wheat fields. However, despite the constant threat of wartime violence, Ukraine has remained committed to continuing grain exports and taking part in humanitarian programs like the Grain from Ukraine humanitarian initiative, which seeks to deliver essential aid to nations such as Syria and Palestine.

More pointedly, Russia’s destruction of Ukrainian grain “also attacks the revered place of bread in Ukraine’s culture, conditioned not only by old beliefs but also by previous experiences of being killed through starvation,” as Tsymbalyuk explains.

Tsymbalyuk draws parallels between Russia’s ongoing destruction of Ukraine’s farmland and the Holodomor, the Soviet-engineered famine that claimed an estimated 3.5 to 5 million Ukrainian lives. In recent years, a number of European countries have recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people. The stories of hunger and starvation passed down through surviving generations instilled in many Ukrainians a deep aversion to wasting food. With this historical context, Russia’s ongoing destruction of farmland during the full-scale war conjures up a legacy of hunger employed as a weapon of control.

The international community has largely overlooked the consequences of Russia’s ecocide against Ukraine beyond the country’s borders, and Tsymbalyuk’s frustration over this grim reality is felt throughout the book.

“Not only has Russia’s war on Ukraine resulted in significant greenhouse gas emissions…it has also led to an increase of militarization globally, as well to an increased carbon footprint from refugee movements, charges of international flight routes, and logistics operations far beyond Ukraine,” Tsymbalyuk writes.

“We cannot address the climate crisis as a global condition without including the (carbon) emissions from the warplanes, rockets, and drones flying over Ukraine today, and without a deeper understanding of the relation between Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and climate change.”

This trespass upon Ukraine’s soil, upon the very fabric of Ukrainians’ way of life, presses on into a denaturalization so profound, it impacts even the dead, disrupting the rituals of mourning and the dignity of burial.”

Tsymbalyuk invokes the diary of Nadiya Sukhorukova, a journalist who survived the siege of Mariupol. Her diary reflects a woman suspended between the fragile hope that, should she be killed by Russia’s guided aerial bombs, her body might remain with all its limbs — and the bitter sorrow of knowing even if that happened, she would likely be deprived the dignity of a proper burial. When asking what to do with the dead body of her friend’s grandmother, a police officer says the best thing to do is leave it on the balcony.

“In Sukhorukova’s diary, death is omnipresent and imminent, but the horror extends beyond death itself,” Tsymbalyuk writes. “The horror persists in the body, a body that continues to testify even and especially in its dismemberment.”

Russia’s war against Ukraine is not only a war against its people — it’s a war against memory, land, and the right to grieve with dignity. Tsymbalyuk’s “Ecocide in Ukraine” is a monumental work that insists the world must reckon with the cost of this destruction — not just in hectares lost or tons of grain burned, but in the severed roots that once tied generations to the land they called home. To read this book is to understand that ecocide is not just collateral damage but a strategy of erasure. And if we fail to name it, to witness it, and to resist it, the horror that outlives the body will come for us all.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about or related to Ukraine, Russia, and Russia's ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. If you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.