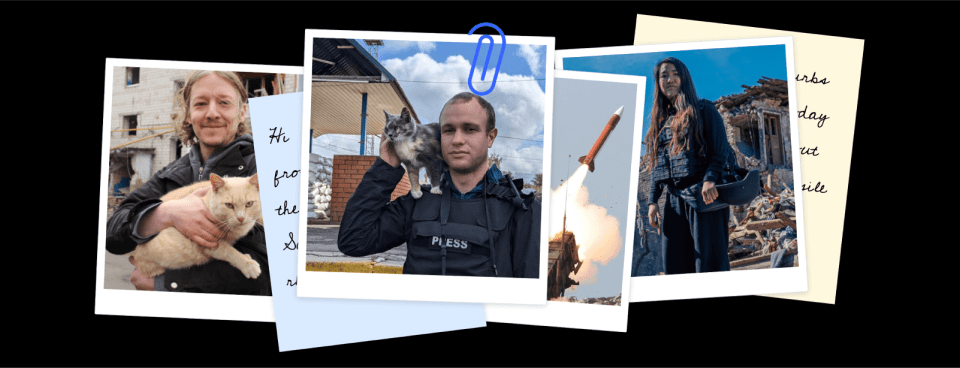

‘I want to go home’: Inside a Russian prisoner of war camp in Ukraine

Editor’s note: The location of the prisoner of the war detention center is undisclosed for security reasons. The Kyiv Independent got vocal recorded agreement from the prisoners of the war to be interviewed and identified in the story.

Undisclosed location in Western Ukraine – Private Alexey Strelkov massages his knee as he sits on a bed in the infirmary at a prisoner of war camp in western Ukraine, hundreds of miles away from the front line.

The former Russian inmate, who was an assault infantryman of Russia’s 61st Naval Infantry Brigade before being captured, spends his time at the camp reading pulp fiction and hoping to be swapped in a prisoner exchange.

Strelkov had six years left to serve in a Russian prison in Perm Krai northeast of Moscow for drug dealing when a Russian army colonel arrived in May with a tempting offer: a pardon in exchange for six months of service, good pay, and generous benefits for his family in the event he died on the battlefield in Ukraine.

The Russian Defense Ministry began recruiting inmates for the war in Ukraine in early 2023 after the ministry itself stopped allowing the infamous Wagner Group to recruit in Russian prisons.

Roughly a week after being recruited, Strelkov took his first-ever flight, landed in Rostov with other recruits, and headed to Russian-occupied Kherson Oblast for a short stop of military training before deployment on the Berdiansk axis, one sector where Ukraine has found moderate success during the counteroffensive.

In early June, just 10 days into deployment and over a month after being recruited, 30-year-old Strelkov suffered multiple shrapnel wounds caused by mortar fire and was captured by Ukrainian forces near the village of Blahodante in Donetsk Oblast, liberated just days later.

“I would go home right now if (Russia) would take me. I hope, believe, and wait (for the swap),” Strelkov told the Kyiv Independent in the hospital wing of the camp with 33 other heavily wounded prisoners of war (POW) and several guards.

After Russian soldiers, mercenaries, and forcibly conscripted Ukrainians from occupied Donbas are captured, they quickly move through a series of detention centers in major Ukrainian cities before arriving at this camp in western Ukraine.

While it’s not the only detention center where Russian POWs are held, it’s allegedly the largest. Ukrainian authorities don’t disclose how many POW centers there are, nor how many Russian POWs are currently in custody in Ukraine.

A prisoner exchange is likely the next step unless the soldier is suspected of war crimes. If convicted, they continue serving time at the same camp, Petro Yatsenko, spokesperson of Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, told the Kyiv Independent at the detention center.

So far, Ukrainian courts have convicted at least 23 Russian POWs for violating the rules and customs of war, according to court records. Their prison sentences are anywhere between seven to 13 years.

Ukraine has secured the return of around 2,600 Ukrainian soldiers during 48 POW exchanges with Russia since the start of the full-scale invasion.

Kyiv, however, doesn’t disclose the total number of Russian POWs swapped, according to Yatsenko. The Russian Defense Ministry’s swap reports indicate that Moscow has brought back 1,220 troops with 20 POW exchanges since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In a comment to the Kyiv Independent, Andriy Yusov, spokesperson for the Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s military intelligence, confirmed that Ukraine has released fewer Russian POWs than Ukrainian POWs it has received in prisoner exchanges.

Strelkov believes he has a good chance to be exchanged as investigators have not suspected him of carrying out war crimes.

“Over 99% of the POWs want to be exchanged to Russia. Those who do not want to be exchanged will remain in the camp until the end of the war,” Yatsenko said.

Those who don’t want to be swapped have either been forcibly conscripted Ukrainians from occupied territories or are former Russian convicts, drafted straight from prisons, who think they might be put behind bars again if they return home.

Arriving at camp

A white-tiled room with several shelves filled with labeled and tied white burlap bags is the first thing that POWs see after arriving at the camp. Newcomers receive prison uniforms and hand over their military uniforms that are returned if and when they are exchanged.

The room smells of the dirt and blood that remains on the stockpiled uniforms.

Yatsenko, the spokesperson, shows two pairs of leather boots, slippers, and two sets of uniforms consisting of blue pants, jackets, t-shirts, striped gray pajamas, socks, and a basic hygiene kit that all the POWs receive.

“We do not provide them with tuxedos,” he quipped.

The monthly budget per prisoner is around $270, according to Yatsenko. It includes everything – clothing, food, and medical treatment. For comparison, the official minimum salary in Ukraine is $180 per month, and the smallest pension is $81.

After arriving, the prisoners take a shower — sometimes the first in weeks — and get a haircut, if needed, in a room called the “barbershop.”

Local medics examine the POWs upon arrival, making note of any existing conditions or injuries, including checking their hair for the presence of lice, “so that later no one can claim they sustained any injuries while in the camp,” said Yatsenko.

The 3rd Geneva Convention text covers the corridor walls leading to the quarantine area, where POWs spend two weeks upon arrival. There are no bars on the windows, some of which are open to allow some air into the rooms.

Ordinary soldiers are kept separate from officers in accordance with international law. The amber-yellow quarantine room has space for 30 soldiers. Lined with two rows of wooden single beds, chairs, and nightstands, it doesn’t resemble a prison cell. The 3rd Geneva Convention prohibits the detention of POWs in prison cells.

Meanwhile, Russia keeps Ukrainian POWs in prison cells, often together with convicted criminals and in proximity to the front line – all of which are prohibited by the convention.

One example is the notorious Olenivka penal colony in occupied Donetsk Oblast, which sits just 14 kilometers away from the front line. In an explosion in Olenivka on July 28, 2022, over 50 Ukrainian POWs were killed and over 100 were injured.

The quarantine room for officers is much smaller. Three bunk beds, six chairs, and a window with bars. There are no officers at the time. Yatsenko said they are “rare guests” here as most of the POWs are low-ranking soldiers.

"POWs are informed about their rights. But fear fueled by Russian propaganda leads them to believe they will be tortured here. However, after the quarantine, they come to realize that no one intends to subject them to torture, and they begin to behave brazenly," said Yatsenko.

Following the two weeks of quarantine, psychiatrists examine the POWs, after which they join the rest in the general camp, where they work and pass the time.

“Medical concerns may arise due to mental health issues. Some of the POWs come from Russian prisons, are drug-addicted, and require additional attention. Some of them have suicidal tendencies,” said Yatsenko, adding that psychiatrists and camp staff closely monitor at-risk POWs after the quarantine period.

The Kyiv Independent asked several POWs at the camp whether they had been mistreated. None of them said so, but guards were around during the interviews.

The first-hand testimonies of swapped Ukrainian soldiers and the media reports suggest that Russian POWs get better treatment in Ukraine compared to Ukrainian POWs in Russia.

In November 2022, a UN human rights agency report documented POW abuses on both the Russian and Ukrainian sides, relying on prisoner interviews that revealed instances of torture and mistreatment. The report provoked anger in Kyiv.

In another report released in early October, the agency said it had observed marked improvement in the treatment in the camp in western Ukraine, notably increased portions of food, and the end of physical exercise as punishment.

Everyday life

The Ukrainian anthem signals the wake-up call every day at 6 a.m. POWs go about their morning routine and head to the large dining hall for breakfast.

The outdoor corridors leading from the residential area to the dining hall and workshops are adorned with portraits of Ukrainian historical figures and brief descriptions. Yatsenko said their presence is meant to debunk Russian President Vladimir Putin's claim that Ukrainians and Russians are the same people.

In his notorious 7,000-word essay from July 2021, Putin articulated his imperialistic vision for Ukraine's role within a broader “Russian world,” asserting that any notion of a distinct Ukrainian identity was artificially created. This line of thinking was one of the justifications for Russia’s full-scale invasion.

POWs form two rows before entering the dining area. A low porch leads to the entrance and a staircase, from where the scent of fresh food wafts down from the second floor. The prisoners go up the stairs with their hands folded behind their backs.

The prisoners are assigned to work six days a week, an obligation under the Geneva Convention. They are paid slightly more than $8 a month, according to Yastenko.

The 1949 Geneva Convention reads that POWs must be paid a fair wage, but that at no time should that wage be less than a fourth of one Swiss franc for a full working day, which is $7 a month today.

International law grants officers the choice to opt out of working. Five POWs told the Kyiv Independent that working in the workshops isn’t too demanding.

The work ranges from washing dishes, cooking food, or baking bread, to assembling paper bags with the inscription "Ukraine is my country" or welding and crafting garden furniture.

Roughly a hundred POWs work in the largest workshop, which also serves as a bomb shelter. In a bright, white open space with large windows, prisoners wrap welded metal frames with plastic that will eventually be ottomans and sofas. The Ukrainian flag sways in the wind outside the window.

They hardly talk to each other, carrying out the monotonous work with utility knives, metal hooks, and compressor stapler guns. Work stops twice during the day. The first time is for a minute of silence to commemorate those fallen in Russia’s war.

"Every day at 9 a.m., POWs pay tribute during the nationwide minute," said Yatsenko, a spokesperson.

There have been reports that Russian POWs have been forced to sing the Ukrainian national anthem or shout Ukrainian national slogans, which Yatsenko denied.

A UN human rights agency report from March described a “widespread pattern” of POWs being forced on film to shout and sing slogans during the initial phase of capturing the Russian POWs. Ukrainian human rights defenders also recorded testimonies of former Ukrainian POWs recalling they were forced to learn and sing the Russian anthem every morning at the places they were captured.

Work comes to a halt for a second time at lunchtime. Gulag slang from the notorious Soviet labor camps era is still used in the dining hall.

A group of POWs serves “balanda” — a Gulag term for prison food, still used by Russian-speaking prisoners everywhere. The lunch consists of a vegetable salad, a thin pea and potato soup, porridge with butter, a meat patty, and several pieces of freshly baked white bread. All the food is slightly under-salted.

Yatsenko, the spokesperson, says the ration is nutritious and planned by nutritionists.

When POWs finish eating, each table takes turns standing up and shouting, "Thank you for the meal" in Ukrainian. The accent typical for Russian-speaking Ukrainians from occupied Donbas occasionally comes through.

Moscow has forcibly conscripted thousands of Ukrainian men from Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts for Russian regular or proxy armies. They are kept alongside Russian prisoners of the war.

Mobilization in occupied territories constitutes a war crime.

Some tables have crutches leaning on them. One pair belongs to Serhii Versdysh, a Ukrainian from Russian-occupied Horlivka near the city of Donetsk who joined Russian proxy forces on the first day of the full-scale invasion.

He ended up in captivity in early June after stepping on an anti-personnel mine, resulting in the loss of his right foot, he told the Kyiv Independent later in the day while in the infirmary.

After being captured, he was interrogated, sent through detention centers in Dnipro and Kyiv, and eventually brought to the camp in western Ukraine.

All prisoners are interrogated at each stage of captivity, including several times at the camp. Strelkov, the captive from Russia’s Perm Krai, was lucky – since his arrival at the camp, he has been interrogated only once.

Versdysh from Horlivka, a Ukrainian town occupied by Russians since 2014, was interrogated multiple times, with each session lasting at least two hours, he told the Kyiv Independent.

As he is a Ukrainian citizen, Versdysh is facing charges of high treason for fighting alongside Russia. If found guilty, he could be sentenced to up to 15 years.

Like many POWs here, he wants to be swapped.

"I’m aware of the punishment (for the high treason). I would like to be exchanged and return home," Versdysh told the Kyiv Independent while in the camps’ sickbay waiting for the online court hearings.