Culture is not neutral: The troubling presence of Russia’s Eksmo in Frankfurt

Visitors look at books at the 2025 Frankfurt Book Fair on Oct. 15, 2025 in Frankfurt, Germany. The Frankfurt Book Fair, which is the world's largest, was open to the public from Oct. 15 until Oct. 19. (Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images)

Kate Tsurkan

Culture reporter

There were two questions lingering over conversations among people at this year's Frankfurt Book Fair: Where was the stand of the Russian publisher Eksmo located, and why were they even allowed to be there nearly four years into Russia's full-scale war against Ukraine?

I will never forget the look of horror and disgust of one exiled Russian author, who is fiercely pro-Ukrainian and quietly attended many of Ukraine's events at the book fair with a visible awe at this year's event program, when he learned that Eksmo had been allowed to return.

In case you're unfamiliar, Eksmo is not just another publishing house — it is one of Russia's largest and most influential literary institutions, the local equivalent of Penguin Random House in scale and impact. For decades, they've shaped what millions of Russians read.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: to keep operating in today's Russia, Eksmo has had to become a part of the system. And that means their catalog includes a fair share of state-aligned, openly anti-Ukrainian titles.

In other words, it's part of the Kremlin's propaganda machine.

Each year, the Frankfurt Book Fair serves as a global meeting point for the publishing industry, bringing together not just book lovers but publishers, authors, translators, and agents from around the world. It provides a platform for the exchange of ideas, the celebration of diverse cultures, and the negotiation of translation and publishing rights that allow literary voices to cross borders. Participating countries typically host their own national stands, showcasing their literary landscapes and cultural identities within the fair's international framework.

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, its official presence at the Frankfurt Book Fair has vanished — there's no large-scale Russia stand showcasing its publishers. And yet, a small handful of Russian publishers like Eksmo have somehow quietly maintained their presence on the fairgrounds.

It seems the old assumption still lingers — that art can somehow exist apart from politics, even in wartime. Sometimes that might be true. But in many cases, pretending there's a clean line between the two only serves those who benefit from blurring it. Deep down, the organizers of the book fair must have known this, given the fact that Eksmo's stand was so well hidden.

Also, it goes without saying, the very existence of a Russia stand, even if there wasn't a war, would be paradoxical and strange. How can Russian publishers come together to celebrate their literature when the overwhelming majority of their most talented living authors are in exile for criticizing the Kremlin, and selling their books within Russia will only bring trouble?

For example, books by Russian authors like Boris Akunin have even been removed from bookstores in Russia because he has been labeled a "terrorist and extremist" and criminal proceedings have even been opened against him in absentia for "justifying terrorism" and "spreading false information" about the Russian military.

Literature that challenges our view of the world and defies existing structures of power — that is, true literature — simply cannot exist in today's Russia. Think of that next time you reflect on your defense of "the great Russian novel."

I'd rather not dwell too much on the strange spectacle that is contemporary Russian culture, though.

This year was my first-ever visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair, and I'm proud to share that I was there at the invitation of Mystetskyi Arsenal, the Ukrainian Institute, and the Goethe-Institut Ukraine, who kindly asked me to moderate three panel discussions — on Ukrainian wartime nonfiction, on discovering Ukrainian literature through translation, as well as a more existential panel exploring the idea that, in the end, everything is translation. There were countless people behind the planning of this year's program of events, and they clearly made an effort to showcase Ukrainian literature and culture from every possible angle.

I can't speak for previous years, but every Ukrainian I met agreed: Ukraine's presence in Frankfurt this year was extraordinary, part of a program that continues to outshine itself year after year. Since the EuroMaidan Revolution of 2014, Ukraine has been steadily reasserting itself on the global cultural stage, carving out a space that exists entirely beyond Russia's long imperial shadow. Events like the Frankfurt Book Fair are just a reminder of how far Ukraine has come since then.

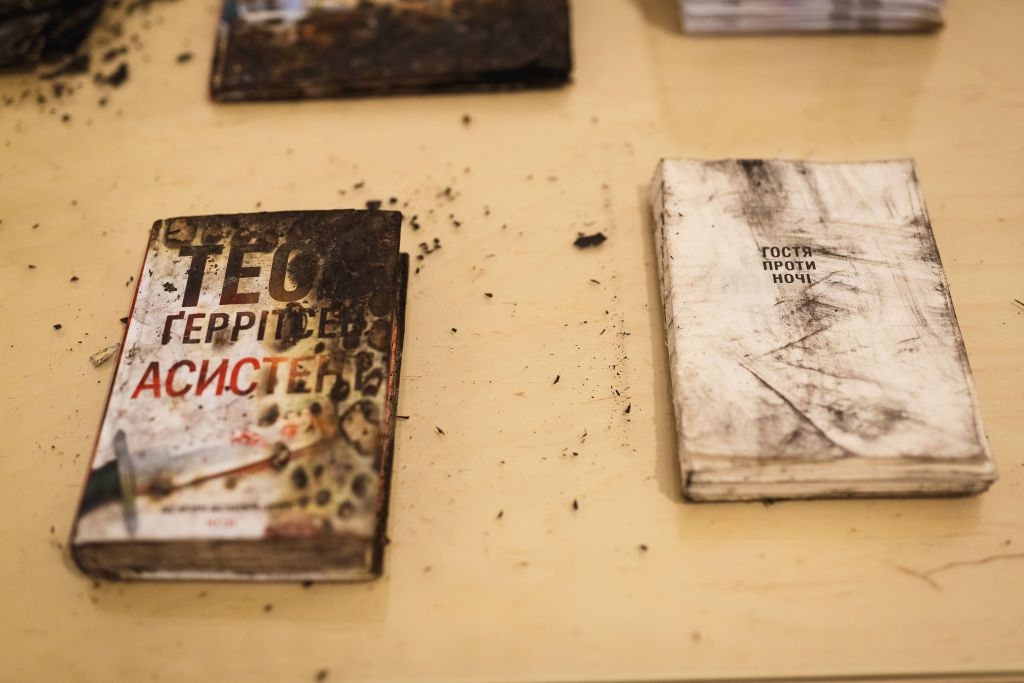

Ukraine's place at the fair was far more than a showcase of recently-published books — it was a proud declaration of the country's cultural identity and resilience amid the full-scale war. It was also a reminder of everything — and everyone — Ukraine has lost since that fight against Russian aggression began. There was a display with the names of cultural figures killed by Russia, with a caption that read: "When they ask me what war is, I'll answer without hesitation — it's names."

As one of the organizers of the display showed me, even during the festival, post-it notes were quietly added as the names of more fallen were announced, a somber testament to the daily horror that persists.

That's why I thought long and hard about one part of the brief conversation I had with that fiercely pro-Ukrainian Russian author after my first day of the festival. He had attended my event on "everything is translation" in which I mentioned in passing the work of Valerian Pidmohylnyi, a Ukrainian writer active during the 1930s who was killed by the Soviets.

Speaking to me after the event, his only critique of my moderation was that, in making such references, I hadn't fully conveyed the horror to the audience. Pidmohylnyi wasn't merely killed — he was brutally executed, along with hundreds of other Ukrainian intellectuals, by the Soviet terror apparatus.

The author observed that too few had spoken out to support Ukraine when it mattered after 2014, too few had named things as they truly are — and now a madman in the Kremlin is rallying his nation of 143.5 million to bring the entire world to the precipice of global catastrophe. The author, telling me this, had once visited Sandarmokh himself, the forest near the Finnish border in northern Russia where Pidmohylnyi and countless others met their deaths. I listened in quiet horror as he described the unnerving realization of how many skeletons of innocent people lie beneath his country's soil.

The next day, when I moderated an event on Ukrainian literature in translation with two authors currently serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, I made a deliberate effort to speak without restraint about what is truly at stake for Ukraine and Ukrainian culture.

Our conversation illuminated a literary tradition that refuses erasure — one that endures, resists, and insists on being heard.

Amid the daily escalation of the full-scale war, one can only hope that Europe finally grasps the gravity of what is at stake. But if military warnings fail to resonate, perhaps the cultural sphere can succeed where politics falter — by refusing to lend its platforms to propaganda, and instead amplifying the voices of those who write, fight, and live for freedom.