In Lukashenko’s Belarus, Belarusian culture is not welcome

While Belarusian is one of the two official state languages in Belarus, the decision to speak, read, and write it can be a dangerous choice for Belarusians.

Growing up, the Belarusian poet and translator Valzhyna Mort was aware of how the Belarusian language was perceived in her country.

“Belarusian was mocked for its ‘village sound,’ and was generally considered useless – a language that couldn’t possibly express daily life in Belarus. This is a sad irony, of course,” Mort told the Kyiv Independent.

The truth was that “the Russian language didn’t express what it means to be a little girl in Soviet Belarus and then, after the Soviet collapse, living in a colonial schizophrenia of waking up in your country in which nothing is actually yours,” Mort added.

In spite of more than two centuries of Russification policies imposed on the country, Belarusian writers say that their language and culture have quietly persevered.

After the eruption of mass protests in 2020 against Alexander Lukashenko's fraudulent presidential election “victory,” more Belarusians became curious about their heritage and how it sets them apart from Russia.

Those publicly doing so might now face imprisonment in Lukashenko’s Belarus.

People who speak Belarusian are considered to be against the regime and have been arrested, fined, or imprisoned on politically-motivated charges. Despite that risk, many see preserving the Belarusian language and culture as continuing their fight for a democratic and truly independent country.

Belarusian language’s precarious status in Lukashenko’s Belarus

After years of oppression, there was hope that a Belarusian cultural revival would follow the dissolution of the Soviet Union. However, that brief window of opportunity was shut by Lukashenko’s rapid accession to power.

After gaining independence in 1991, Belarus' national white-red-white flag and the Pahonia emblem – now symbols of resistance against Lukashenko’s dictatorship – were made official symbols of the country, and the Belarusian language enjoyed support from the state.

For a brief moment, Belarusian was the country’s sole official language.

After Lukashenko took power, a hardline approach toward the country’s culture and language was introduced.

Lukashenko became president in July 1994 and, in 1995, he put forward a referendum that would also make Russian an official state language.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) later released a report suggesting that Lukashenko’s government had purposefully attempted to influence the outcome of the referendum, as well as the parliamentary elections held that year.

The legality of the 1995 referendum has been questioned by legal scholars and human rights organizations, as well as members of the Belarusian opposition.

Lukashenko has also been publicly challenged over the years by politicians and journalists alike for favoring the Russian language over Belarusian.

Additionally, he has said that Russian dictator Vladimir Putin “thanked” him for “not demonizing” the Russian language as Putin claimed had been done in other countries.

Despite his assertion that using either language is a legitimate choice, Lukashenko has conveyed on numerous occasions that he perceives the Belarusian language as inferior.

“People who speak Belarusian cannot do anything, because nothing great can be expressed in Belarusian. The Belarusian language is a poor language. There are only two great languages in the world: Russian and English,” he famously said back in 2006.

In 2023, you will rarely hear Belarusian on the streets of Minsk and other major cities, while the white-red-white flag and the Pahonia emblem can land you in jail.

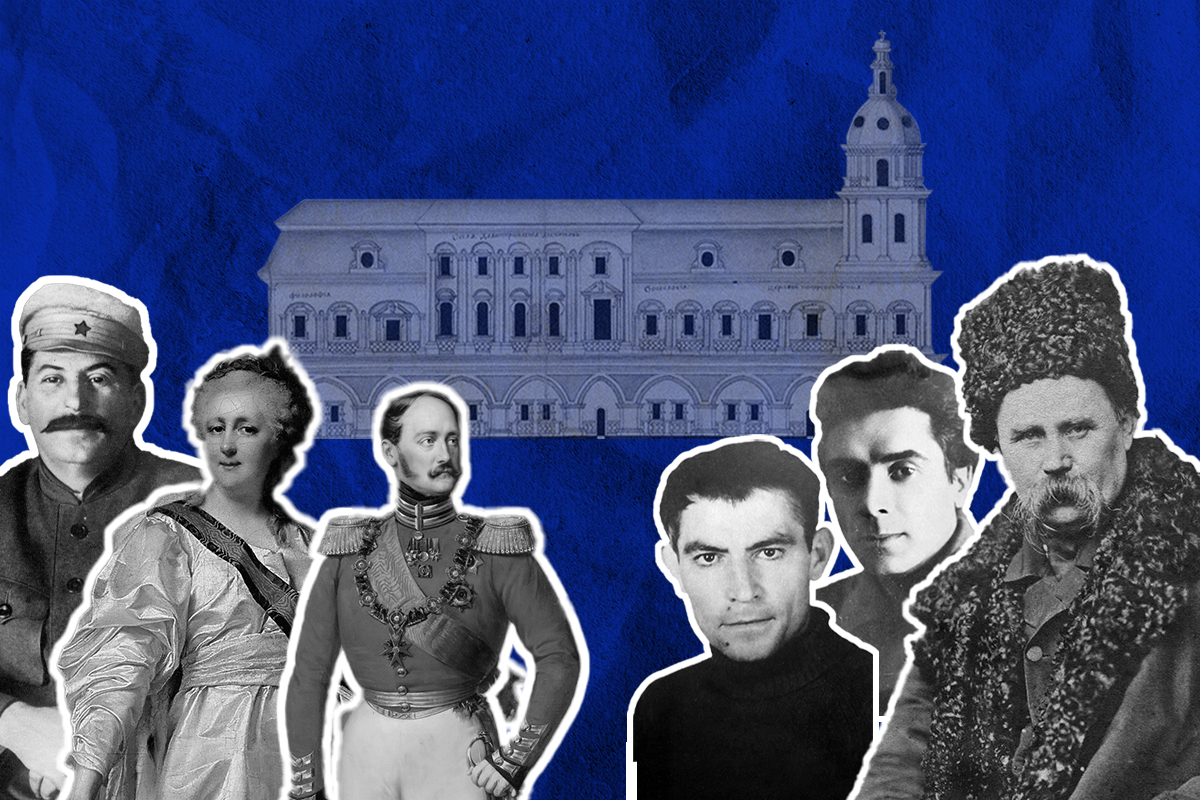

Centuries of Russification

For generations, Belarusians have been discriminated against, attacked, and even killed for embracing their culture.

Tsimokh Akudovich, a Belarusian historian who works with the media platform Belsat, told the Kyiv Independent that Belarusian nationalism has always been deeply rooted in the unique sense of Belarusian cultural identity and shaped by the Belarusian language.

“The Belarusian language has always defined the geographical boundaries of our nation and became a place of accumulation of intellectual resources and images. All of Belarus’ political movements during the last 100 years were strongly tied to the Belarusian language and culture,” Akudovich said.

According to Akudovich, this is why every power that set out to subjugate the nation was keen on attacking the language and those who spoke it.

During the Soviet Union, authorities made a point of targeting Belarusian cultural figures.

While there was a brief period in the 1920s when Belarusian language and culture were permitted to thrive, it was followed by two decades of brutal repressions. As a result, only a handful of Belarusian writers, musicians, and academics managed to survive – many were sent to the gulags or killed outright.

The Holocaust also devastated the Belarusian Jewish population. According to Swedish-American historian Per Anders Rudling, Belarus used to have one of the largest Jewish populations per capita in Europe.

Prior to that, the Soviets targeted the Jewish cultural revival in Belarus. Yiddish was once a language commonly heard spoken in major cities and towns, in addition to Belarusian, Polish, and Russian.

In his article “The Invisible Genocide: The Holocaust in Belarus,” Rudling wrote that no less than 800,000 Belarusian Jews perished in the Nazis’ efforts to conquer Europe.

After World War II, the Soviets undertook a significant urbanization project in Belarus, forcing the rural population to move to cities and learn Russian. This reshaped the linguistic makeup of Belarus.

“Former villagers brought their language with them, but it was not welcomed. Russian was the language of the state and power and of the comfortable urban life,” Belarusian poet and translator Julia Cimafiejeva said.

This led to a rise in the usage of “trasianka,” a mixture of Belarusian and Russian that is still commonly heard today and incorporates Russian vocabulary with Belarusian grammar and phonetics.

It is a similar linguistic phenomenon to “surzhyk” in Ukraine, which is a mix of Ukrainian and Russian.

During the post-war period, the Soviets employed subtle tactics to undermine the importance of the Belarusian language.

Scholar Lieanid Lyč wrote that in the late 1950s parents were allowed to petition for their children to be transferred from Belarusian- to Russian-language schools.

“The architects of such an anti-national language policy in the education field understood very well that if only the Russian language prevails in all higher and secondary educational institutions in Belarus, if all types of official records are conducted exclusively in it, then practically none of the parents will insist that their children were taught and brought up in their native Belarusian language,” he added.

This fostered a belief among many Belarusians that knowing Russian had more value.

By the start of the 21st century, some Belarusians worried that the Belarusian language would disappear from everyday usage.

However, Russia “could not completely destroy the roots of Belarusian national identity” and “despite ongoing pressure from Moscow, there has been a gradual expansion of the Belarusian language and culture,” Akudovich said.

Two Belarusian literary scenes

Julia Cimafiejeva and Alhierd Bacharevič, the husband and wife literary duo who currently live in exile, took part in the mass protests of 2020 and have explored what it means to be Belarusian in their bodies of work.

Cimafiejeva was born in a village along the Belarusian-Ukrainian border that was evacuated in 1986 after the nuclear fallout from the Chornobyl disaster. When she entered school in Homiel, the second-largest city in Belarus, “learning to speak Russian competently and correctly was a necessary, although not prescribed, condition to be accepted,” she wrote.

However, both noted that the Belarusian language could always be heard somewhere on the radio or TV, or read in newspapers and magazines, while they were growing up. Predominantly Belarusian-language schools also existed, although they were usually in villages.

Belarus has never been perceived in terms of strictly Belarusian- and Russian-speaking regions. The use of either language typically depended on your background and where you wanted to be in life, Cimafiejeva added.

Bacharevič echoed that sentiment, adding that the Belarusian language was never a “dead language,” but it remained, for a long time, deeply undervalued.

“We studied Belarusian language and literature at school, but most people did not understand why. After all, the Russian language dominated,” he said.

In the 2010s, the Belarusian literary scene of which Cimafiejeva and Bacharevič were an active part existed in two separate realities.

The Union of Writers, established in 2005, was backed by the Lukashenko regime. Its members enjoyed privileged access to state-controlled media outlets, such as TV channels and newspapers. They also received frequent invitations to appear at educational institutions.

Their language of choice was Russian. However, choosing to write in Russian has never been a definitive marker of being aligned with Lukashenko’s regime. Cimafiejeva, Bacharevič, and Mort have all worked in both Belarusian and Russian during their careers.

Additionally, Belarus’ most famous writer, the 2015 Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich, writes predominantly in Russian. Most of her work has been published outside of Belarus, given her longstanding history of publicly opposing the Lukashenko regime.

Despite state-level support, those belonging to the Union of Writers “could not provide a bright image of the new future of the dictatorial state,” according to Cimafiejeva.

Meanwhile, independent authors existed “in a kind of cultural ghetto,” she added.

Since their work was exposed to a much smaller audience, this relative obscurity actually provided Belarusian writers with a certain degree of freedom for a period of time.

Belarus’ independent cultural sphere launched various initiatives during this period to cultivate interest in Belarusian language and literature, where writers had the chance not only to connect with their peers but engage with their readers.

Belarusian authors also faced the daunting task of competing against the massive influence of the Russian market. Cimafiejeva told the Kyiv Independent that the majority of the books sold in Belarus in 2019 were imported from Russia.

By contrast, Belarusian-language books, most of which were educational materials, were far less common.

Initially, the Belarusian cultural movement was not perceived as a threat by Lukashenko’s regime. However, following a series of protests against fraudulent elections over the years, that started to change. Literary magazines, publishing houses, and other cultural institutions soon found themselves under growing scrutiny and became targets for closure.

The writer’s association PEN Belarus told the Kyiv Independent that there is essentially a ban on the profession for those who speak out against the regime.

This is because the cultural and artistic initiatives undertaken by Belarus' independent cultural scene over the years influenced, to a certain extent, the protests and shaped the political consciousness of the people, according to Cimafiejeva.

“They helped their audience to feel the urge to self-identify themselves as Belarusians and be freer in a political sense,” she explained.

Repressive measures further escalated after the mass protests that began in 2020, which led to the exile of Cimafiejeva, Bacharevič, and countless others.

According to PEN Belarus, there is “permanent discrimination on the basis of the Belarusian language” given that it is associated with opponents of the regime.

“Not only do we live in exile; Belarusian publishers also live in exile, our readers live in exile, a lot of people have left Belarus and for the last few years we all try to survive and develop our culture in these difficult conditions,” Bacharevič said.

In 2022, Bacharevič’s novel “Dogs of Europe” was banned by the Belarusian authorities as “extremist literature.” It's an expansive novel with several interweaving storylines that unfold over several decades. Set in a dystopian world, it depicts a reality where Russia has taken over Belarus and several other countries to become a dictatorial superstate.

Bacharevič wrote on Facebook in July that he’d learned Belarusian authorities planned to plow over confiscated copies of the book with tractors.

His novel “The Last Book by Mr. A” was also banned in 2023, he said in a recent interview. Merely possessing a copy of these books in Belarus can now land an individual in trouble.

Meanwhile, PEN Belarus told the Kyiv Independent that there are 132 members of Belarus’ cultural sphere currently being held in Lukashenko’s prisons, which amounts to an estimated nine percent of all political prisoners in the country officially registered by Viasna human rights group.

However, Lukashenko’s crackdown has targeted not only Belarus’ literary sphere but the artistic sphere as well. People from all walks of life in Belarus face imprisonment, torture, and murder for daring to want to live in a democratic country.

The renowned artist Ales Pushkin died from “unclear circumstances” in prison on July 11. He was arrested on politically motivated charges in 2021 after the Belarusian authorities claimed one of his paintings “rehabilitated and justified Nazism.”

In 1999, Pushkin famously marked the five-year anniversary of Lukashenko’s ascent to power by dumping a red wheelbarrow full of manure at the main entrance of the Presidential Office in Minsk, placing a photo of Lukashenko on top of the manure, and piercing it with a pitchfork.

He also flew the historic white-red-white flag over his home and said back in the 90s that Lukashenko did nothing good for Belarus and its people.

“Ales was an incredibly talented, provocative, and courageous artist – and a good man,” Bacharevič wrote.

“He will remain an artist and a person who was killed in prison, killed by this government. He was killed for language, talent, and bravery – for being Belarusian,” Bacharevič said, adding that “this murder cannot be forgiven.”

An ongoing cultural revival

Despite increasing attacks on those who dare to speak the language, more Belarusians are writing in Belarusian, speaking it, reading it, and realizing why they need it.

This is critical given that there is no state-level support for the Belarusian language and Lukashenko’s regime is destroying Belarusian culture, PEN Belarus told the Kyiv Independent.

Cimafiejeva started using Belarusian more frequently back in 2006. Like many other Belarusians, it was a conscious decision made in the climate of protests against election fraud.

She also started working for Belarusian-language independent media and entered an educational institution that taught mostly in Belarusian.

“I had a quite wide circle of people speaking Belarusian, but it was a learned language for them all,” she said, given the prevalence of speaking Russian, especially in Belarus’ major cities.

Only in the past 20 years have more children born in cities been raised to speak Belarusian as their native language, according to Cimafiejeva.

“I’ve become more optimistic about the fate of the Belarusian language, especially if you compare today’s situation with the situation we had in the 1980s or even the 1990s,” she said.

Although Belarusian cultural initiatives lack state support, and much of their work is being done in exile, they are dedicated enthusiasts who believe in what they are doing and are trying to spread it to wider audiences.

Embracing the Belarusian language and culture can also be a means of comfort when processing the impact of having lived through a failed revolution, being faced with exile, and witnessing the outbreak of Russia’s genocidal war in neighboring Ukraine, of which the Lukashenko regime is an unofficial participant.

“People are seeking clarity in ideas and in language, which is to say in literature, and in the language of the arts in general. Emotions are intense and it's music and visual arts that can reflect that intensity without putting on labels, without naming. So, in these periods of crisis, the demand for art is high,” Mort said.

Likewise, Bacharevič explained that a lot of Belarusians realized after 2020 that the system they lived in “was built on lies and violence.”

“In 2020, these people started reading more Belarusian literature because they need answers to their painful questions: who we are, how this (political) disaster became possible, what our past is, and where we are going now,” he said.

Despite Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine being one of the factors that have influenced many Belarusians to establish closer ties with the Belarusian language and culture, not all Belarusians are ready to cut the Russian language out of their lives completely.

Belarus has never been a monolingual state, and Cimafiejeva does not expect Belarusian to be the only language spoken in the country.

“Although I do want to see a better future for it,” she added.

Previously, Bacharevič translated many of his novels into Russian himself. He is of the belief that knowing many different languages is always beneficial, but he still considers himself first and foremost a Belarusian speaker.

“I think in Belarusian and dream in Belarusian,” he said. “The Russian language is our colonial heritage. I have not forgotten it, but I rarely speak it, mostly when I speak with Russians.”

Mort said she doesn’t consider the Russian language itself a problem but rather those who promote the destructive ideology of the Russian regime.

Her main issue with the Russian language has always been that it doesn’t allow her to express herself as freely as the Belarusian language does and that it has denied Belarusians a sense of pre-Russian history and agency.

“The Russian language doesn’t understand the Belarusian countryside,” she said.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. Since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there's been a lot of talk about Ukraine's cultural revival. However, Belarusians and people from other neighboring countries are reckoning with years of Russian colonialism as well. Culture has taken on an even more important meaning during wartime and if you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting our reporting.