Hungary takes helm of Council of EU. Should Ukraine be worried?

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban. (Zoltan Kovacs/X)

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban arrived in Kyiv on July 2, in what became his first visit to Ukraine since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion.

The visit came two days into Hungary's rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union, also known as the Council of Ministers. The position in the hands of arguably the most Russia-friendly member state caused some concern in Ukraine.

Taking over from Belgium in July, Budapest will remain in this role until Jan. 1, 2025, when it will pass the presidency to Poland.

Ukrainian concerns may be misplaced, however, given not only the limited powers of the presidency but also the "lucky" timing of its duration.

Under Belgian chairmanship the EU managed to clear the most consequential issues pertaining to Ukraine, while the aftermath of the European elections is certain to occupy the bloc's attention for months to come.

The (limited) powers of the presidency

The Council of the EU is one of the Union's three key institutions. It gathers ministers of the 27 member countries in various configurations to approve and shape legislation proposed by the European Commission.

The Council's chair can outline its agenda for the six months of the presidency's duration.

The presidency also chairs most ministerial meetings, drives legislative work, and represents the Council in dealings with the European Parliament and the European Commission.

"To do this, the presidency must act as an honest and neutral broker," the position's description says, a statement that might raise a few eyebrows given Budapest's reputation as the EU's troublemaker.

Orban has become something of a black sheep in the EU, regularly lashing out against "Brussels bureaucrats" while drawing criticism about the domestic rule of law issues and democratic backsliding.

Orban began the presidency with the motto "Make Europe Great Again," mimicking the adage of his fellow populist, former U.S. President Donald Trump, who is seeking to return to office.

In his listed priorities for the presidency, Orban mentioned more stringent measures against migration and a "focus on peace and European interests," referencing the war in Ukraine.

The Hungarian prime minister and his top diplomat, Peter Szijjarto, have repeatedly frustrated their European colleagues by obstructing assistance for Ukraine and sanctions against Russia, claiming that arming Kyiv will lead to "escalation" and prolongation of the war.

While in Kyiv, Orban urged President Volodymyr Zelensky to consider a ceasefire in order to "speed up peace talks."

"I asked the president to think about whether we could reverse the order, and speed up peace talks with making a ceasefire first," Orban said in a statement to reporters after the two leaders met.

While Budapest eventually lifted its veto of Kyiv's membership talks and later the 50-billion-euro ($54 billion) financial package for Ukraine, it continues to block 7 billion euros ($7.5 billion) in defense assistance.

In spite of this worrying record, Budapest's possible influence via the presidency is quite limited.

The Lisbon Treaty in 2009 stripped the position of many of its key responsibilities. Its role of presiding over the European Council—meetings of EU heads of state and government —passed to the new position of the European Council president, currently held by Charles Michel, who is set to pass his duties to António Costa on Dec. 1.

The year 2009 also saw the establishment of the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who represents the EU outside of the block and chairs the meetings of foreign ministers.

Josep Borrell, who has led the EU's diplomacy since 2019, is expected to be soon replaced by Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, a well-known Ukrainian ally.

The presidency lacks hard powers, and the preset priorities are often drowned by unexpected developments and crises, the Center for European Reform writes.

"The presidency is most importantly a technical role," which a given member country usually uses to "showcase itself," said Dorka Takacsy, a fellow at the Center for Euro-Atlantic Integration and Democracy and the German Marshall Fund, in a comment for the Kyiv Independent.

Hungary may also not necessarily seek to stir trouble during its presidency. Undisclosed official sources from various member states told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty that Hungarian officials have conducted themselves professionally during preparations for the chairmanship.

The Hungarian government itself "seemingly aims to play down (the presidency's) importance as well, and put the whole presidency to a technocratic light," Takacsy said.

"The situation is somewhat peculiar, as the current government actively paints the enemy picture of 'Brussels' in its rhetorics for over a decade now, so it is a dissonant thing that Budapest has to be 'Brussels' for half a year now," the expert added.

Fortunate timing

Another key reason why Ukraine can breathe a sigh of relief is the favourable timing of Hungary's presidency.

Belgium did its homework in clearing the Kyiv-related agenda before Hungary took over. The EU officially launched the accession talks with Ukraine and Moldova on June 25 and adopted the 14th sanctions package just a day earlier.

Ukraine and the EU also managed to finalize a bilateral security agreement in June, and the disbursement of the Ukraine Facility tranches is well underway.

With these important processes launched, further accession talks can be left for presumably more Kyiv-friendly Polish presidency in 2025, leaving Hungary to focus on EU enlargement efforts in the Western Balkans.

Publicly, while visiting Kyiv, Orban pledged to support Ukraine "in everything we can" during the country's presidency.

Takacsy warns that Budapest may still turn to "confrontative rhetorics related to Ukraine as it did until now," but there is nothing it can do to cause "irreversible damage."

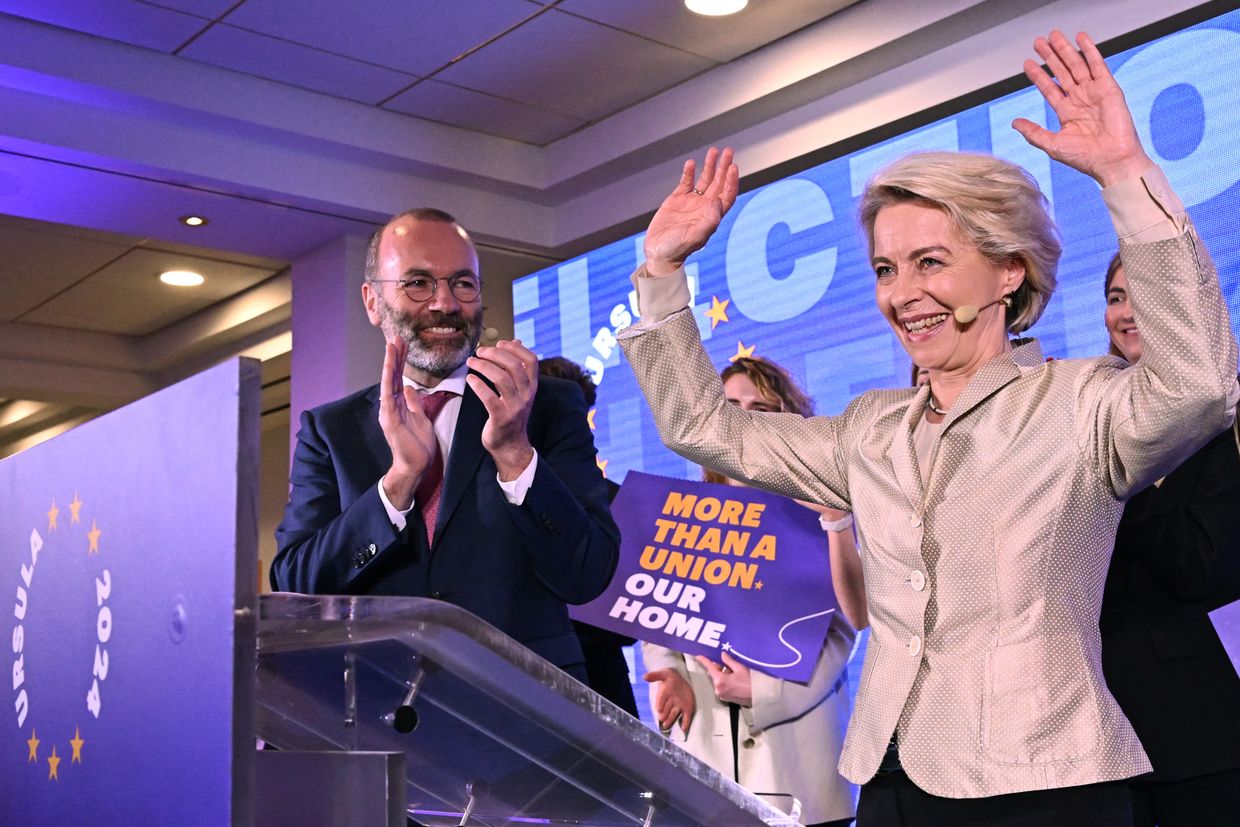

Additionally, Hungary took over the presidency only weeks after the European elections, which means that any legislative work will likely give way to the formation of a new European Commission.

While Orban's confidence may be bolstered by the growth of Euroskeptic right and far-right parties and the prospects of forming his own group in the European Parliament, the presidency has no say in the negotiations on the Commission's makeup.

The EU's executive arm, which is also the sole body with the right of the legislative initiative, can take months to form, chipping away at Hungary's limited window of opportunity to impose itself on the legislative process.