‘Evil must not win’ — how Ukraine’s female partisans resist Russian occupation

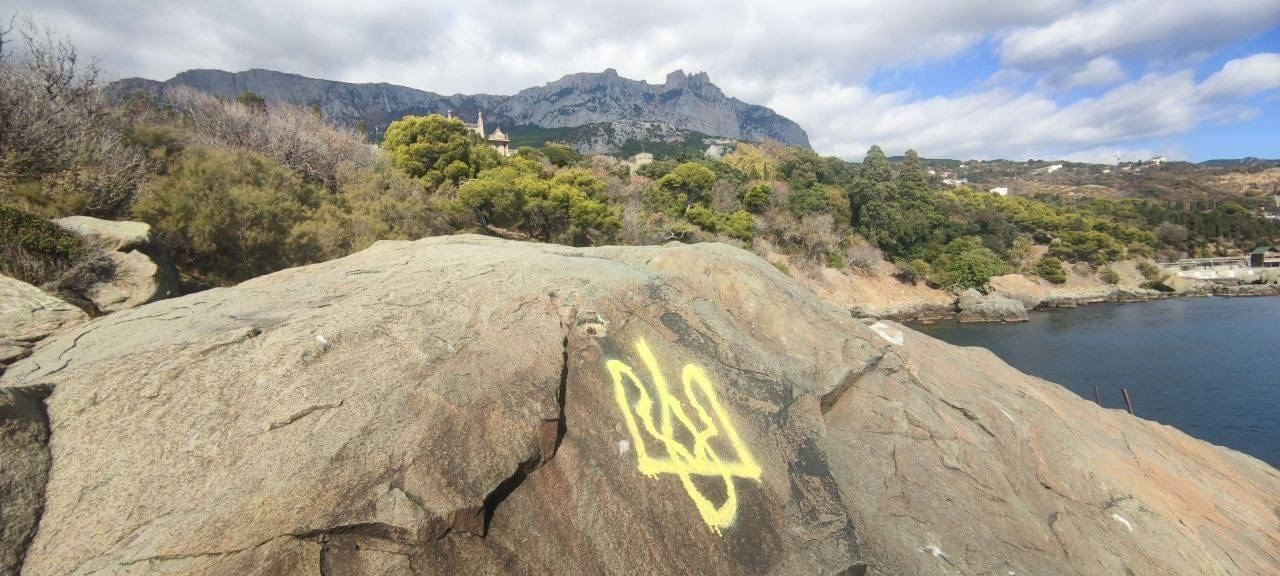

Art created by Zla Mavka, a Ukrainian all-female resistance group operating in Russian-occupied territories. (Zla Mavka)

Somewhere in the streets of Russian-occupied Simferopol, the capital of Crimea, a woman puts a sticker on the wall. It’s a short message, but if she is seen doing it, she will face arrest, prosecution, and likely, torture.

The message is: "Soon, we will be home again." On another sticker, the most dangerous three words in the occupied Crimea: "This is Ukraine."

What makes it even more risky for their bearer is the language. The words are in Ukrainian.

The woman putting up the stickers is a member of Zla Mavka, an all-female resistance group. She is on a dangerous mission: to give hope.

In the occupied territories, hope is a prized commodity. As Russia's full-scale war is about to reach its grim third anniversary, its grip over one-fifth of Ukraine's territory has only grown tighter.

The prospects for full military liberation of the occupied regions — including Crimea and parts of the Donbas region occupied since 2014 — seem ever more distant.

After seeing the liberation of the parts of Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Kherson oblasts in 2022, Ukrainians in other occupied areas have been hoping that their turn will come soon. Now they struggle to find comfort in the latest news.

Nonetheless, Olesia, one of the three women who founded Zla Mavka, an all-women resistance movement that operates across occupied territories, including Crimea and Zaporizhzhia Oblast, says she plans to fight as long as possible. Olesia’s name has been changed and her last name is not being disclosed to protect her identity as she lives under Russian occupation.

"As long as there is hope, we will continue to resist," she told the Kyiv Independent.

The name, Zla Mavka, or Angry Mavka, harkens back to old Ukrainian folklore — the mavka is a woodland female spirit who uses its beautiful appearance to lure men to their deaths. An image of a young woman, clad in white garb and wearing a wreath of flowers, became the most iconic attribute of their imagery.

Mavkas are not easy to reach. Their members never know when a Russian soldier will stop them in the street to inspect the contents of their phones.

Olesia sends her answers in writing through an intermediary. Audio or video is deemed too risky. Her responses are somber and free of embellishments.

"If we lose, we won't have a life here," she writes. "We will have to leave our homes because living under Russian occupation is worse than prison."

Mavka cocktail

Olesia comes from a city in southeastern Ukraine that was seized by Russia mere days after the outbreak of the full-scale war.

After Moscow illegally declared the annexation of the lands they seized, hers and other cities under Russian control were to be remodeled into Potemkin villages — a veneer of a harmonious cohabitation covering up arrests, torture, and repressions.

On Women's Day on March 8, 2023 — more than a year after the start of the occupation — Russian troops were lined up in the city's streets to dutifully hand out flowers to Ukrainian women. The gesture had a different effect than Russia might have hoped.

It was the "insolence of Russian occupiers and their attitudes toward women" that inspired the founding of Zla Mavka, Olesia explains.

"We wanted to remind them that they are not at home, that this is Ukraine, and they are not welcome," she says.

"We wanted to remind them that they are not at home, that this is Ukraine, and they are not welcome."

The trio of founders, one of whom is an artist, began distributing posters bearing an inscription in Russian reading "I don't want flowers! I want my Ukraine back!" and a drawing of a woman smashing a Russian soldier with a bouquet.

Since these early days, the movement grew to hundreds of activists, forming a decentralized group coordinated through anonymous chatbots on a messenger app. The group spread to different occupied regions and became especially active in Crimea, with a few members hailing even from Donbas.

Zla Mavka may be only one of several resistance groups that sprung up in Russian-held areas, including the Yellow Ribbon and Atesh. But its all-female character and the use of humor and creativity sets it apart from others.

Creativity is the group's greatest strength, Olesia says, half-jokingly suggesting that women can be more sophisticated in the ways of resistance than their male counterparts.

Among the many acts of resistance since the foundation of the group, Mavkas say they created fake ruble banknotes reminding the Russians that "Crimea is Ukraine," burned Russian flags, and filled the streets with pro-Ukrainian graffiti, posters, and poetry. At times, they say they mix laxatives into food and alcohol served to Russian soldiers, a treat they mischievously dubbed the "Mavka cocktail."

Their activities also venture into more usual resistance activities, including the distribution of self-published newspapers to counter Russian propaganda or — according to the Ukrainian military-run National Resistance Center — passing information about the Russian military to Ukraine.

But Olesia emphasizes that Zla Mavka is more than just a resistance group. It has become a source of support for Ukrainians amid the hardship of occupation — a community where anonymity is no obstacle to connection.

Omnipresent fear

"It's disgusting, nauseating," Olesia says as she describes what she feels seeing Russian soldiers in the streets of her hometown every day.

"It's especially difficult when you have to talk to them. You want to say everything you think about them, scratch out their faces, I don't know what… but you have to be discreet and not reveal anything."

The Mavka diaries, vividly illustrated stories written by individual members and published by the group on social media, present poignant accounts of life under Russian war and occupation.

"We held on to the last moment but had to leave for Zaporizhzhia," reads one of the diaries, published in February 2024. "My husband stayed in Mariupol. Forever. My heart remained there, right in the yard of our house that we had been building with love for so long. We buried him in our yard.”

Omnipresent fear and suppression of Ukrainian identity have become eponymous with the Russian occupation.

Ukrainian citizens are denied medical care unless they accept Russian passports. Men are forcibly drafted to fight against their own country. The Ukrainian identity of children is being erased in schools before they're sent off to "patriotic" military training camps.

"I have never felt so much fear in my life as I do now. Being under occupation, I constantly feel in danger; I fear for my life. I am afraid that they will come for me and imprison me for supporting Ukraine. I am afraid that they will torture me. I am afraid that I will never see my son," reads another passage from a Mavka from Starobilsk, a city in Luhansk Oblast occupied since March 2022.

"I am afraid that they will come for me and imprison me for supporting Ukraine. I am afraid that they will torture me."

Even for those who do not plant bombs under railway tracks or report the movement of Russian troops to Ukrainian authorities, the realities of the occupation are unavoidable and deeply personal. Displaying Ukrainian symbols is punished, and people are afraid to speak the Ukrainian language.

It is in the acts of resistance, great or small, that Ukrainians find strength while living under occupation.

"You feel that you are doing something for which you will not be ashamed to look your children in the eyes, that you are helping, that you did not break," Olesia explains.

But every time, it is as scary as the first time, she admits, using a common Ukrainian saying that translates to: "The eyes are scared, but the hands are doing."

The fate of millions

At the time when Zla Mavka was founded, the hope felt across Ukraine was palpable. Not only were Russian forces humiliated in Kyiv Oblast, but Ukrainian counteroffensives in the fall of 2022 liberated dozens of towns and villages in Kherson and Kharkiv oblasts, including the city of Kherson.

But then a new counteroffensive, the long-awaited one that was meant to cut into Russian lines in Zaporizhzhia Oblast in the summer of 2023, didn’t succeed.

Since then, the front line has been moving in Russia’s favor, with Ukraine suffering a series of painful losses in the eastern Donetsk Oblast.

Both Kyiv and its Western partners now acknowledge that a liberation of Ukrainian land by force of arms is unlikely in the near future. As U.S. officials propose ceasefire deals that would leave millions of Ukrainians under Russian occupation, hopelessness is creeping in.

"It's scary. People are thinking about options of what to do if it happens," Olesia says of a ceasefire that would leave the occupied lands under Russian control.

"Many people despair, many are trying to decide how to live (under the occupation)."

News from the front line brings no comfort as well, as Russia continues to raze and capture new villages, one by one.

"Sometimes it seems that behind all those headlines about territories and kilometers, some forget that these are all people, lives, homes, destinies," Olesia says.

As it’s capturing more Ukrainian land, Russia is also tightening its grasp on the occupied territories, according to Olesia. The occupation administration has ramped up surveillance, with increasingly common security checks and more cameras in the streets.

Even the initial advantage that Mavka held — that Russian soldiers would not suspect women to be resistance members — has lost its edge as the occupiers grow more careful, Olesia says.

It is hard enough to fight against overwhelming odds in constant fear. It is harder still when hope is in short supply. In spite of this, the Mavkas fight on.

Talking about what keeps her motivated, Olesia says laconically, "Somebody has to do it. It just happens to be us."

Although layered with melancholy, her messages reveal a sense of purpose and perseverance.

"The power is in the people. Each of us has the power to do something to help this world, from a leaflet to big decisions in the world's seats of power," she says in a message from occupied Ukraine to the free world.

"We are here, and despite everything, we continue to resist because evil must not win. Please fight with us and for us."

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Martin Fornusek.

With our team, we strive to bring you true stories of the Ukrainian resistance, of the bravery of Ukrainian men and women like Olesia defying Russian occupation for so many years. We wouldn't be able to do so without the support of readers like you. To help us continue in this work, please consider becoming a member of the Kyiv Independent's community.

Thank you very much.