Exclusive: New insights point to Hungary’s collaboration with Moscow on transfer of Ukrainian POWs

In early June, a bizarre and mysterious joint operation was carried out between two of Ukraine’s neighbors, one to the east and one to the west.

Eleven Ukrainian soldiers, after having been held in Russian captivity for an unknown amount of time, were moved from Russia to Hungary.

Although Ukraine and Russia have regularly exchanged prisoners of war, sometimes via third countries like Turkey and Saudi Arabia, this time, Ukraine was not informed about the operation beforehand, nor has Budapest provided any information to Kyiv about the Ukrainian citizens on its territory in the weeks following.

Despite the extreme political sensitivity of such a move, both Moscow and Budapest, where the transfer was proudly confirmed by Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjén, have denied any direct state role in it, with Hungary claiming that the transfer was organized strictly between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta.

New information obtained by the Kyiv Independent in collaboration with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Hungary (RFE/RL Hungary) from Ukrainian officials and diplomatic sources, as well as others in Hungary familiar with the matter but unable to go on record due to the sensitivity of the subject matter, gives clues to the direct involvement of the Hungarian state in the transfer.

Hungary has so far adopted a line of plausible deniability, enabling Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to escape greater international scrutiny for the events, which ― whether initiated by Hungary or passively agreed to ― are unprecedented for an EU and NATO member state in the middle of Russia’s full-scale war.

The information also points to a severe deterioration of working diplomatic contact between Kyiv and Budapest, which has consistently undermined Ukraine’s defense of its territory and sovereignty from inside the EU and NATO since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

So far, five of the 11 Ukrainian POWs in question have returned to Ukraine. According to Petro Yatsenko, spokesperson for the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, they eventually made contact with the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry, which organized their transport by car across the land border.

The whereabouts of the remaining six, who could in theory have relocated to other countries in the Schengen zone, as of Aug. 1 could not be confirmed by Ukrainian officials, who said they are still trying to organize their return to Ukraine.

‘Humanitarian mission’

The handing over of Ukrainian servicemen was initially announced on June 8 by a short press release from the Russian Orthodox Church, which claimed that the move was “part of inter-church cooperation, at the request of the Hungarian side.”

The news was confirmed on the next day by Semjén, Hungary’s deputy prime minister, who said that his personal role in coordinating the transfer was his “human and patriotic duty.”

Though Semjén described the release of the Ukrainian POWs to Hungary as a “gesture to Hungary” by the Russian Orthodox Church specifically, there is no distinction on the Russian side between the church and state as an actor. Even putting aside the well-documented status of the church as a political arm of the Vladimir Putin regime, the POWs were captured and held, like any others, by the Russian military, which would need to approve any such handover.

On the Hungarian side, questions were immediately raised about the knowledge and involvement of Orbán and his government upon the announcement of the transfer.

Perhaps giving away more than he should have, Hungarian government spokesman Zoltán Kovács wrote in a June 9 tweet that the transfer was coordinated by Semjén and “carried out at the request of Hungary,” adding that the Maltese Charity Service “also participated in the transport.” The tweet remains up as of Aug. 1.

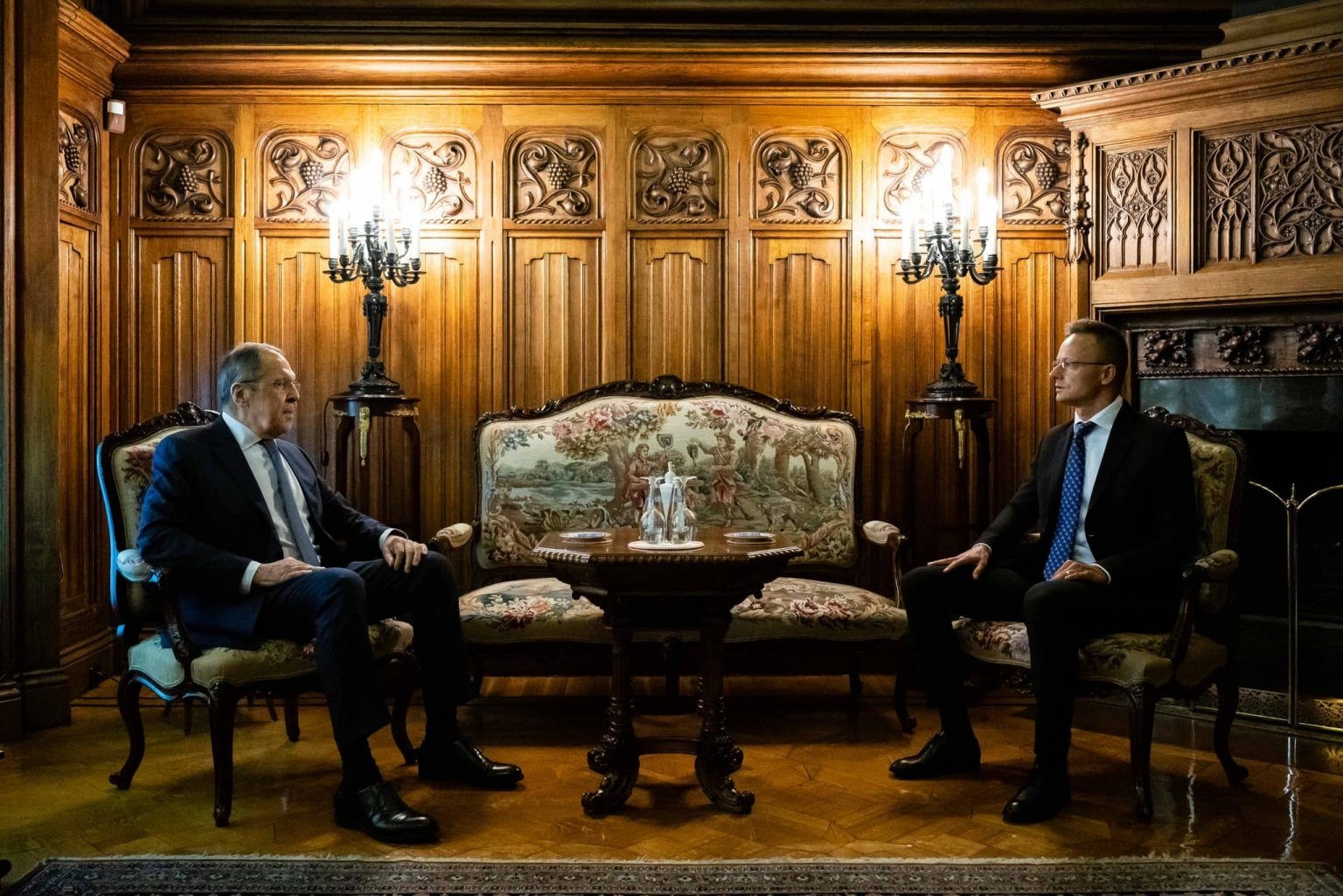

Despite that, speaking at the European Parliament in Strasbourg on June 20, Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó denied the government’s involvement.

“There were discussions between church and religious organizations, where the state of Hungary was absolutely not involved,” further claiming that the soldiers were now free to move around in Hungary or return to Ukraine as they pleased.

The statements of Kovács and Szijjártó openly contradict one another, as the latter claims that the negotiation was strictly between two religious bodies, while Kovács describes the role of the Maltese Charity Service as a facilitating one, helping Semjén with logistics.

According to several anonymous sources cited by RFE/RL Hungary in June, neither Szijjártó nor Gergely Gulyás, the head of the Hungarian prime minister’s office, were made aware of the planned transfer.

According to one anonymous diplomatic source interviewed for this article, the prisoners were brought to Hungary via Turkey, as all direct air travel between Russia and the EU has ceased.

The source could not confirm if they stayed any amount of time in Turkey, or with what kind of flight they came, while Ukrainian officials also declined to comment on the details.

According to open-source flight data, there were no observed flights on government planes between Turkey and Hungary on the days when the transfer was to occur, though there was a flight by a small jet belonging to Maltese charter flight company VistaJet on the afternoon of June 7 from Istanbul to Budapest.

One of the main questions, of course, is the role and knowledge of Orbán himself in the transfer. Beyond being Deputy Prime Minister, Semjén is the leader of Hungary’s Christian Democratic People's Party, the partner of Orbán’s Fidesz party in the ruling coalition, and a close political ally of the prime minister.

“It is hard to imagine that the top leadership of the country did not know about this operation,” Ukrainian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Oleg Nikolenko said to the Kyiv Independent. “We are sure that they knew about it, and that this work was authorized at the highest level.”

Not bound by diplomatic language, Dmytro Tuzhanskyi, director of the Institute for Central European Strategy, a Ukrainian think tank, was more blunt.

“Semjén is an extension of Viktor Orbán, especially in matters of Russia, especially in such sensitive issues as the transfer of prisoners of war,” Tuzhanskyi told the Kyiv Independent. “He would not have taken a single step or said a single word if Viktor (Orbán) had not allowed him to do so.”

Orbán himself has so far not made any public comment on the transfer. According to a Hungarian source familiar with the matter, an internal government directive stated that only Semjén should speak on it.

Given that Hungary’s leader was almost certainly made aware, further questions arise about whether the initiative for the transfer came from Moscow or Budapest.

For both sides, according to the sources interviewed, the main aim was to publicly discredit Ukraine by painting a picture of ethnic Hungarian soldiers made to fight for Kyiv against their will, and under threat of being sent back to the front or even court-martialled if they returned to Ukraine.

For Hungary, possible motivations also align with Budapest’s posturing since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion: that of peacemaker and protector of Ukraine’s ethnic Hungarians.

In between calling for negotiations with Russia and the removal of Western sanctions, Orbán regularly repeats Kremlin propaganda narratives on the war he says was provoked by the West, which is “fighting to the last Ukrainian soldier" in its “proxy war” with Russia.

Hungary was nonetheless quickly thrown off by the Russian church’s early announcement and the quick reaction from Ukraine, according to Hungarian expert on Russian affairs András Rácz, who said the announcement placed Budapest in a “painful communications situation.”

“I've heard many times that Semjén is called a useful idiot, not only on Russian issues,” added Tuzhanskyi. “In this context, Hungary has consciously become a useful idiot.”

Both the Hungarian Foreign Ministry and Semjén's office were contacted for comment, but did not respond as of the time of publication.

POWs turned political pawns

As accusations were exchanged between Budapest and Kyiv, next to nothing was known about the prisoners themselves.

On June 15, RFE/RL Hungary reported, citing anonymous officials and diplomats, that the servicemen had been captured during battles near Kupiansk in Kharkiv Oblast. Yatsenko confirmed to the Kyiv Independent that the five who eventually returned were known to Kyiv as prisoners of war, rather than missing persons.

Oleg Kotenko, Ukraine’s Commissioner for Missing Persons in Special Circumstances, reported on June 19 that Kyiv had established the surnames of the 11 soldiers.

Hungarian officials, including Szijjártó, frequently called the POWs “Transcarpathian,” referring to Ukraine’s Zakarpattia Oblast on the border with Hungary. The region has a large Hungarian minority: according to the 2001 census, the only one ever conducted in independent Ukraine, around 150,000 ethnic Hungarians made up about 12% of the region’s population.

According to Fedir Sándor, a Hungarian-Ukrainian professor at Uzhhorod National University, soldier, and appointed Ukrainian ambassador to Hungary, around 400 ethnic Hungarians are serving in the Ukrainian military, and 34 have been killed in action. Most of them fight together in units of the 101st Territorial Defense and 128th Mountain Assault brigades, both based in Zakarpattia Oblast.

When news of the transfer broke, the assumption was quickly made in the media that the POWs were from this Hungarian minority, a story which would fit with the Orbán government’s long-running discourse of stopping Hungarians from dying in the war as a justification for appeasing Russian aggression in Ukraine.

The truth, flagged by the diplomatic sources interviewed and tacitly confirmed by Yatsenko, is different. While the POWs allegedly do have Hungarian-sounding surnames, only one speaks Hungarian and is a Hungarian citizen; the rest were identified as members of the Rusyn community, a loosely-defined group of local Slavic peoples speaking a local dialect of Ukrainian.

This reflects the reality of the ethnic tapestry of Zakarpattia Oblast, where Ukrainians, Hungarians, Slovaks, Romanians and other people have mingled for centuries.

“These are Ukrainians who simply have some Hungarian background, but they are representatives of the Ukrainian state, the Ukrainian political nation,” said Yatsenko.

More importantly, the fact that all but one of the POWs identified as Hungarian shows that for those who coordinated the transfer with Moscow, it was the thinly-veiled image of saving Hungarians that mattered: who these people were in reality did not.

“What worries us is that we do not hear these people, that it is these people who do not express their position,” said Oleksandr Kononenko, representative of Ukraine’s ombudsman, to the Kyiv Independent.

Kept in the dark

Once the Ukrainian soldiers arrived in Hungary, very little was known publicly about their whereabouts and the conditions in which they were kept.

The picture painted both by Kyiv officially and by anonymous diplomatic sources is one of a gray zone in which the lines between freedom and custody are blurred.

One anonymous source close to the Maltese Charity Service said that the POWs were housed in a dormitory building owned by the organization in Budapest, although the Kyiv Independent has not been able to verify this.

“It's definitely not captivity. Of course, this is a slightly different situation,” said Kononenko.

Still, Ukrainian officials speaking on the record claim that, contrary to what Budapest has said, the POWs were deprived of basic human freedoms in their stay in Hungary.

“We know, for example, that they are kept in one place; some relatives were able to come to see them, but they met in a different place other than where they are kept,” said Nikolenko.

“The relatives came to the designated place, and the Hungarian side brought these prisoners. We know that they also did not have free access to, for example, mobile phones or free access to information.”

According to Kyiv, the soldiers were also subject to psychological manipulation of a coercive nature while in Hungary.

“We have information, and this is confirmed by those Ukrainians who returned to Ukraine, that they were subjected to psychological pressure there, they received distorted information,” said Nikolenko, who added that at the time of the interview, this process was continuing with the POWs still in Hungary.

The narrative of this manipulation, as confirmed by the diplomatic sources, was to convince the POWs that they would immediately be returned to the front line or tried as deserters if they returned to Ukraine, with one source claiming that they were even pressured to take Hungarian citizenship.

The five who did return to Ukraine, according to Yatsenko, are currently undergoing physical and mental rehabilitation, as is standard practice with all exchanged Ukrainian prisoners of war.

“They returned, despite all the threats, all the manipulation, and all the offers to stay on the territory of Hungary,” he said.

“They will also receive all the necessary rehabilitation, according to our state rehabilitation programs for those who return from captivity in the aggressor state.”

In all the interviews conducted with Ukrainian officials, comments on the personal restriction and mental manipulation of the POWs in Hungarian territory were made in passive voice, declining to confirm whether those actually carrying it out were employees of the Hungarian state.

When pressed on the matter, Nikolenko and Yatsenko both turned to the phrasing “the Hungarian side,” but were reluctant to give more details.

Yatsenko did confirm that at the organized meetings of the POWs with their relatives, “third-party individuals” were present.

“Were they representatives of the Hungarian side, were they military personnel, did they have any authority?” he said. “I can't confirm who they were exactly, but they were the representatives who were always present at meetings with relatives (of the POWs) in Hungary.”

The implications behind this language match Kyiv’s claims that the Orbán government must have been aware of and involved in the transfer. There is no evidence to how or why a religious charity could take such coercive measures with people apparently in its care.

Beyond the physical circumstances of the POWs’ stay in Hungary, what has publicly concerned Ukraine more is the complete lack of cooperation or communication with the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry, which made repeated requests for consular officials in Budapest to be put in contact with its citizens, as is standard diplomatic practice.

“The Hungarian state should have done everything possible if the person wanted to contact the embassy,” commented Hungarian international law expert Tamás Hoffmann.

“Religious groups cannot detain people, they belong to sovereign jurisdiction. Only the state should be at work here.”

Both Nikolenko and Kononenko drew comparisons to Turkey’s role as a third-party mediator in the exchange of Ukrainian POWs from the siege of Azovstal in Mariupol last year.

“Turkey acted within the framework of the Geneva Conventions,” said Kononenko.

“It was a third party during the relevant negotiations, and everything was coordinated with both the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Ukraine was fully aware of the type of pretext for everything that was going to happen.”

Stab in the back

On July 14, Andrii Yusov, spokesperson for Ukraine’s military intelligence agency (HUR) said that the Russian Orthodox Church was planning a second similar transfer of Ukrainian POWs to Hungary.

According to an unnamed source in Ukrainian security services cited by RBK Ukraine on the topic, Hungary has only agreed to receive more Ukrainian POWs if they are strictly of Hungarian background.

Yusov did not respond to the Kyiv Independent’s requests to comment on the potential second transfer.

Whatever the fate of the Ukrainian POWs remaining in Hungary, the transfer is just the latest escalation in Ukraine-Hungary relations, already strained before Russia’s full-scale invasion and worsening ever since.

In the EU, Orbán’s government has consistently roadblocked the passing of financial and military aid for Ukraine, and sanctions packages against Russia. One of Budapest’s objections notably concerned personal sanctions against Russian Orthodox Church leader Patriarch Kirill, citing it a violation of “religious freedom.”

Kirill, who is well-known as a direct political tool of Putin, has denied Russian atrocities in Ukraine, going so far as to call the full-scale invasion a “sacred war.” Thanks to Hungarian demands, Kirill was removed from the sanctions list.

“We see that against the background of EU efforts to isolate Russia, imposed sanctions, and deprivation of funding and resources for the war, Hungary is actively developing cooperation with Russia under various pretexts,” noted Nikolenko.

In recent weeks, Orbán has declined to call Putin a war criminal, and repeated a regular claim that Ukraine is no longer a sovereign nation because of the state’s reliance on macrofinancial support from the West.

“Right now, Russia is trying to tear Ukraine to pieces,” lamented Nikolenko.

“So to stab Ukraine in the back during the most difficult period of its history is the worst thing that can be done by a foreign government… but it is even worse if it is done by a neighbor.”

This article was produced in collaboration with Flora Garamvolgyi, a journalist writing for RFE/RL Hungary.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Francis Farrell, cheers for reading this article. I grew up on the other side of the world, but in Ukraine I have found a home unlike any other. Just like with so many of our readers, I understand that you don't have to be from near here to realize how important Ukraine's struggle is for freedom and human rights all over the world. The Kyiv Independent's mission is to lead the way in continuing to bring the best homegrown, English-language coverage of this war, even if the rest of the world's attention starts to fade. Please consider supporting our reporting.