On the evening of Feb. 24, Nataliia Sivak received a terrifying message from her younger brother, Ukrainian soldier Yakiv Nehrii.

"Tell everyone I love them very much," the message read. "We are under heavy attack."

It was the last time she heard from him.

When Russia launched its full-scale war against Ukraine, naval infantry sergeant Nehrii, 22, had been serving on Ukraine’s Snake (Zmiinyi) Island, a small but strategically important outpost in the Black Sea.

He was taken prisoner alongisde other Ukrainian defenders when Russia temporarily occupied the island. Ukraine eventually pushed Russian troops from Snake Island in late June.

Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk said in June that 75 Snake Island defenders had been taken prisoner by Russia. On Nov. 7, Ukraine's Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets said that 30 of them had already returned home.

Sivak's brother was not among them.

She knows that Nehrii is being held in Russia but has no details about the state of his health or the conditions he is being kept in.

To help release her brother from captivity, Sivak has advocated for the exchange of the Snake Island defenders on social media and at meetings with the authorities in charge of prisoner swaps.

One day, she believes she will again hug her dear brother.

"I know he is hoping I will get him out of there," Sivak said.

According to Vereshchuk, 2,500 Ukrainian POWs were in Russian captivity as of late September.

Over 1,000 Ukrainians have been returned from Russian captivity since the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion, according to the Defense Ministry's Intelligence Directorate. Kyrylo Budanov, the directorate’s head, said that Ukraine is continuing to negotiate an "all-for-all prisoner swap" with Russia, but the process takes a long time.

A letter from captivity

A former soldier herself, Sivak said her brother had yearned to join the military since seeing her wear the uniform. Their family was not surprised when he joined the National Ground Forces Academy in Lviv before being transferred to the 35th separate naval infantry brigade.

Nehrii was deployed to protect Snake Island on Feb. 3, three weeks before the full-scale invasion.

Located around 35 kilometers off the shore of Ukraine's southwestern Odesa Oblast, Snake Island spans less than a quarter of a square kilometer. Despite its small size, the island is critical for controlling the western Black Sea, according to Budanov.

Nehrii saw Russian warships "circling" far from the island nearly a week before the all-out war, according to Sivak. He also saw them on Feb. 23.

Despite her brother’s observations, Sivak said she never expected the nightmare that followed the next day.

Snake Island became a celebrated symbol of Ukrainian resistance in the early days of the war when Russia's Black Sea warship Moskva arrived at its shores to request the surrender of Ukraine’s guard. "Russian warship, go f*ck yourself," one of the border guards responded. Then, the Russian ship bombed the island.

Sivak said Nehrii had texted her throughout the day, saying Ukrainian forces were being heavily shelled and that there was nowhere to hide from the attacks.

"They were simply falling to the ground to save themselves,” she said.

In his last messages to her, Nehrii had said goodbye. Overnight on Feb. 25, she lost contact with him.

When President Volodymyr Zelensky said in February that 13 border guards had been killed defending the island, he didn’t mention the marines. That omission sparked hope for Sivak that her brother was still alive.

Two days later, she saw Nehrii in a video published by Russian media. "It was such a relief that he survived," Sivak said. "At the same time, I realized the danger he was in."

The Red Cross has confirmed in March that Nehrii was among the prisoners taken. Sivak has been reaching out to Ukrainian authorities and the Red Cross for almost nine months to learn more about his situation.

"Although I have three children, I often have to leave them and go to Kyiv to fight for my fourth child," said Sivak, who currently lives in Khmelnytskyi Oblast. "My younger brother is like a child to me," she added.

Out of nowhere, she received a letter from Nehrii in June. The Red Cross verified it, she said.

"It was written in Russian, and the first paragraph was clearly dictated," she said.

In a brief, hand-written letter, Nehrii said that he was "good, alive, and healthy" and was being kept in Russia. He also said he loved them and that he would be returned home "as soon as everything is over."

Nehrii turned 22 in July. Sivak says she did not celebrate his birthday. She also did not celebrate her and her children’s birthdays this year.

"We will celebrate only when my brother returns home," she said, crying. "I want to believe he will."

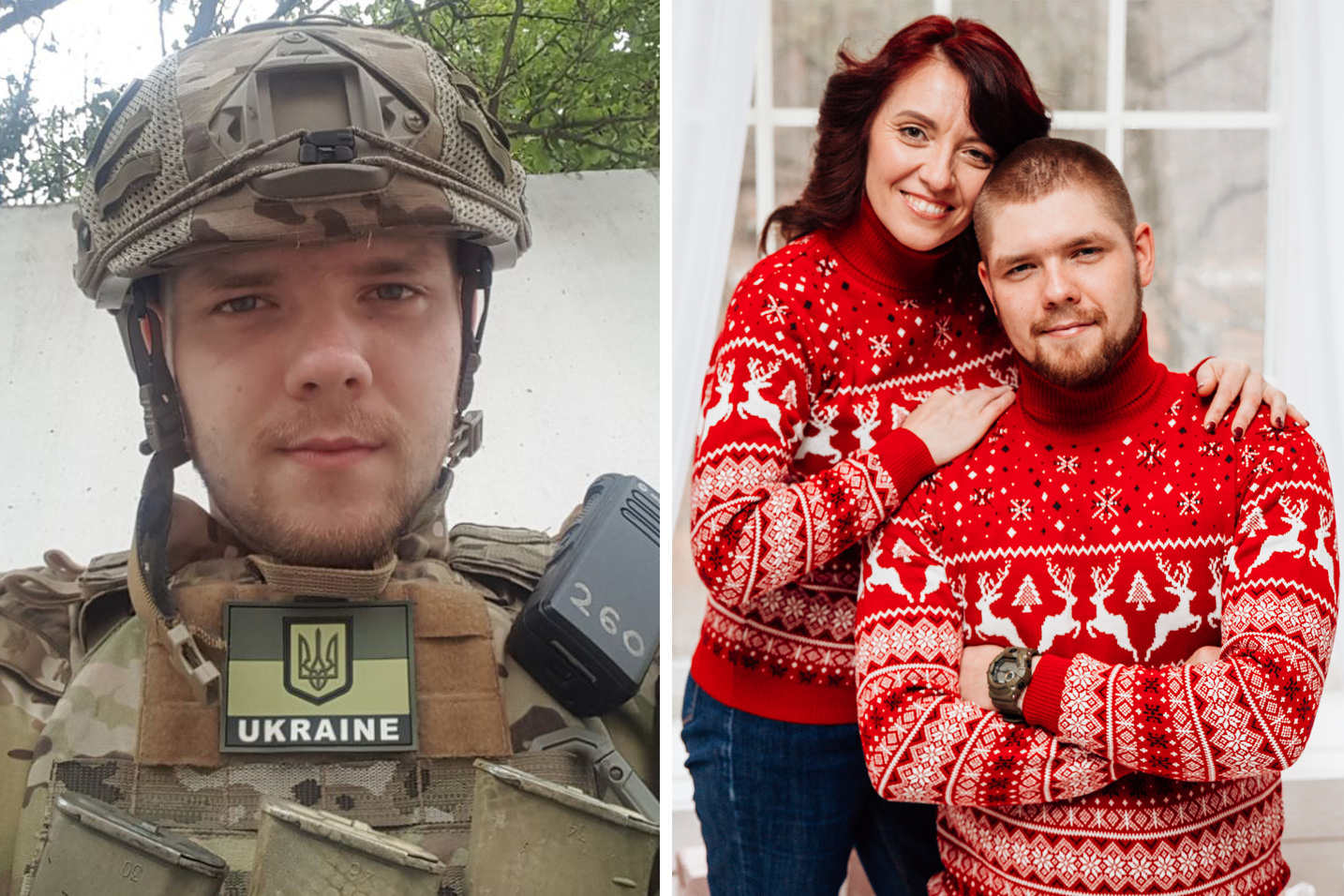

'His jacket keeps me warm'

Ukrainian teacher Liudmyla Yesiuk is usually energetic and cheerful in class. But behind her smile hides the heart-wrenching pain of knowing that her only son, 25-year-old soldier Vladyslav Yesiuk, is a prisoner of war.

"How can I continue living my life if I don't know where my child is," she said.

Yesiuk said her son dreamed of becoming a soldier since childhood. He chose to join the Azov Regiment, part of Ukraine's National Guard and one of Ukraine's best-trained and most effective combat units.

When Russia started its all-out war on Feb. 24, Yesiuk was in their hometown of Bila Tserkva, Kyiv Oblast, while her son was in Mariupol, Donetsk Oblast. He was defending Mariupol before Russian forces fully occupied the city.

While Mariupol was heavily bombarded by Russia from day one, Vladyslav tried to downplay it when talking to his mother, not wanting her to worry.

He also did not tell her that he got a concussion and was treated at a hospital in the Azovstal steel plant, Ukraine's last stronghold in Mariupol. Around 2,000 Ukrainian soldiers and civilians, including children, were trapped at the giant plant during Russia's siege of Mariupol.

During his time at the plant, Vladyslav also lost two fellow soldiers with whom he was close: "He used to say that a fellow soldier is closer than just a friend," Yesiuk recalled.

Weeks after not having heard from her son, Yesiuk received a text message sent by an unknown phone number saying, "I'm alive, do not respond."

There was again silence until May 16, when Vladyslav wrote to her saying they would soon be evacuated from the plant.

Under the UN- and Red Cross-mediated deal between Ukraine and Russia, the defenders of Azovstal were brought to Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine in May. Of the Ukrainian soldiers captured, 211 were transferred to occupied Olenivka. Yesiuk said her son was among them.

In late July, over 50 Ukrainian prisoners of war were killed in what is believed to have been a Russian attack on a prisoner camp in Olenivka. Vladyslav’s name was not on the list of those killed.

Yesiuk believes that her son is alive and is hoping he will return home. In October, Ukrainian law enforcement confirmed that Vladyslav is on a list for prisoner exchanges.

Several prisoner swaps have taken place since then, including the Nov. 3 exchange when Ukraine returned 107 POWs, 74 of whom were Azovstal defenders. However, Yesiuk’s son was not among them. She is still waiting for her son’s release.

"Whenever I'm cold, I put on his fleece jacket," she said. "It warms me up, and it somehow makes it easier."

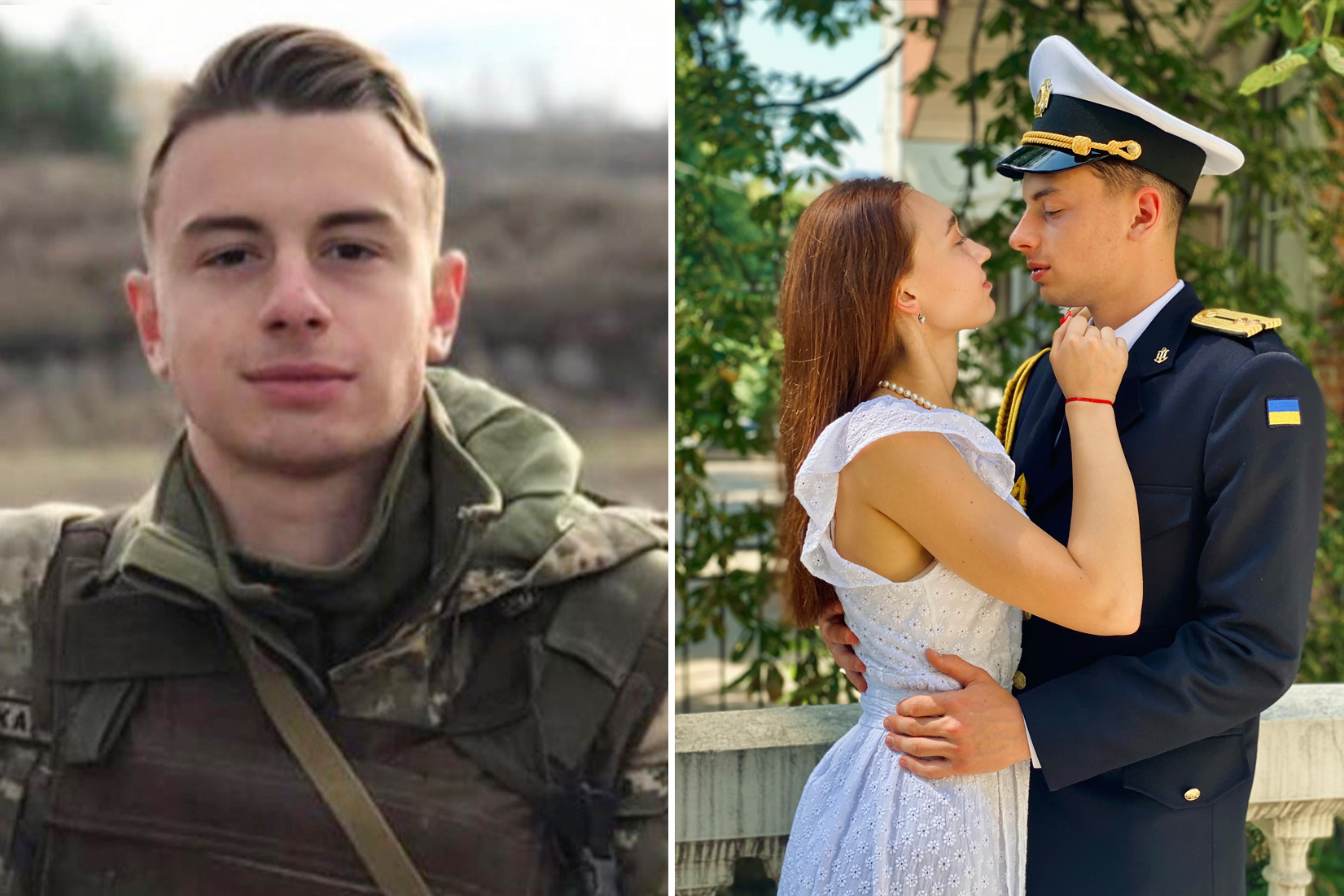

To be married

On one gloomy cold day in early February, Ukrainian student Kateryna Tsareva and her boyfriend, soldier Denys Kharchenko, stood at the central train station in Kyiv, hugging and crying.

"I did not want to let him go," Tsareva said. "As if sensing something."

After a short leave together, he returned to Mariupol, where he served with the 36th marine brigade, while Tsareva went to Kharkiv, her hometown.

Kharchenko, 22, was studying at the Kharkiv Aviation Institute when he met Tsareva in 2020. He dreamed of becoming a pilot but could not pursue it due to a health condition. Instead, Kharchenko joined the naval infantry.

By the age of 21, he had already become a platoon commander and was deployed first to Mykolaiv and then to Mariupol.

"Ukraine's Armed Forces was the right place for him," Tsareva said. "He was doing what he had a talent for."

When the all-out war started, Kharchenko was near Mariupol. Tsareva said they were rarely able to talk to each other then, but she could hear the horrific sounds of war — artillery and missile attacks — as they spoke on the phone.

“They were not sleeping or eating there," Tsareva said. "I could feel that it was very difficult for him."

Though she could rarely hear his voice, she would find other ways to make sure he was alive: Tsareva would reach out to his fellow soldiers, their relatives, local medics, and others who could tell her at least something about him.

On April 7, after a month-long silence, Kharchenko sent her a message.

"He said he loved me and that he hoped he would get a chance to tell me everything that had happened because it was a living hell," she said.

He has not yet had that chance. On April 17, Tsareva discovered Kharchenko had been captured. She saw him on the Russian news.

Tsareva said she watched the video he appeared in a million times, trying to spot every detail possible. Soon, a video of his interrogation was released – it was filmed in Russian-occupied Donetsk, she said.

"I was in shock, of course, but I knew we would bring him home."

Following the major prisoner swap on Sept. 21, when Ukraine returned 215 POWs, one of the released soldiers told Tsareva that he had seen Kharchenko in the prisoner camp at Olenivka and that he was transferred to Russia.

Kharchenko called his mother and Tsareva in September. She was incredibly happy to hear from him. However, the date of his release remains uncertain, as Russia has not yet even confirmed that he is in captivity.

But Kharchenko has “not lost hope that he will return,” Tsareva said.

While the couple is not officially engaged, Tsareva calls Kharchenko her fiancé, saying they both know they are meant to be together.

During their last phone call in September, Tsareva joked that they could get married at any time through Ukraine’s state mobile app Diia. Kharchenko responded that they would have a real wedding, saying "she only has to wait" for his return.

So she is waiting.

______________________

Note from the author:

Hi! Daria Shulzhenko here. I wrote this piece for you.

Ever since the first day of Russia's all-out war, I have been working almost non-stop to tell the stories of those affected by Russia’s brutal aggression. By telling all those painful stories, we are helping to keep the world informed about the reality of Russia’s war against Ukraine. By becoming the Kyiv Independent's patron, you can help us continue telling the world the truth about this war.