Hiding in plain sight — how Russia’s cultural centers continue to operate in US, Europe despite espionage claims

Despite sanctions and espionage claims, Russia’s Russian House centers still operate in the U.S. and parts of Europe. How do they get away with it?

Russian cultural centers maintain operations across US and Europe amid ongoing espionage allegations. (Lisa Litvinenko/The Kyiv Independent)

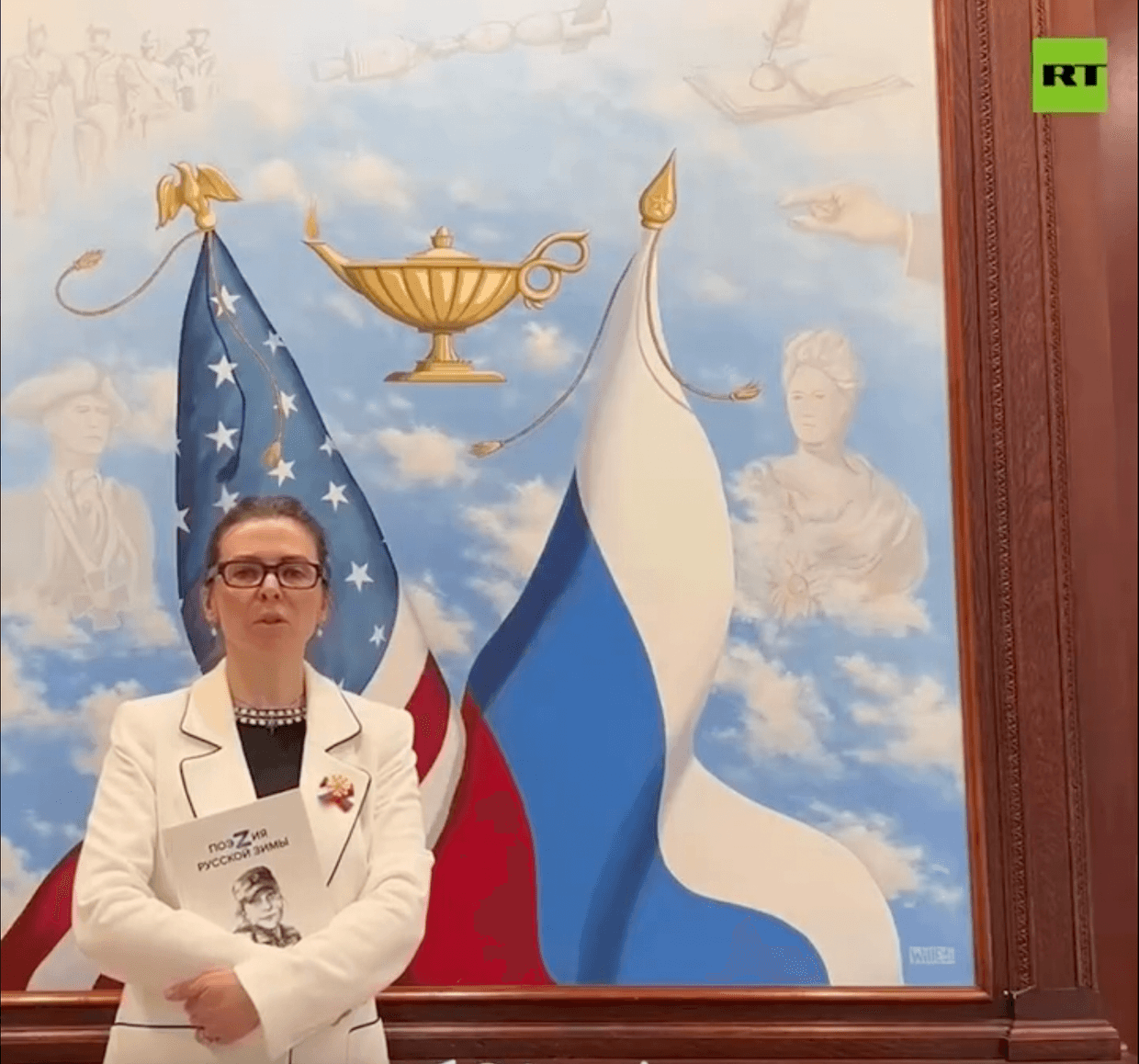

In the video, Russian activist Anna Kiryakova reads from a book of poetry that glorifies her country’s war against Ukraine. The anthology’s title — “Poetry of the Russian Winter” — is written with the Latin Z in place of its Russian analog.

The inclusion of that one letter aligns the book with the Kremlin’s pro-war narrative. Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Z has become a pro-war symbol that many Ukrainians and opponents of the invasion equate with the Nazi swastika.

The most shocking thing about the recording was the location. Kiryakova read the poem inside the Russian Cultural Center in Washington, D.C.

The poem in question was written by a Russian war correspondent and included in the book at the behest of Margarita Simonyan, one of the Kremlin’s most notorious propagandists.

The video was published by Russian state television this February, as the U.S. was negotiating with Russia in a bid to end the war, which has taken the lives of tens of thousands of Ukrainians since 2022.

This bizarre occurrence — a Russian activist reading pro-Russian war poetry in the heart of a country that says it wants to stop the war — is emblematic of the work of the vast global network of Russian Centers for Culture and Science, more commonly known as Russia Houses.

Officially, Russian Houses are intended to promote Russia’s culture, language, and, more importantly, its vision of the world. Their activities range from hosting poetry readings and film screenings to awarding scholarships to Russian universities and organizing fully-funded trips to Russia.

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, they have faced growing scrutiny for serving as a vehicle for propaganda, disinformation and, as some allege, espionage.

But closing them down has proved to be a tall order for Western governments.

Despite European Union sanctions against their parent entity, Russian House continues its activities in Brussels, Berlin, Paris, Rome, Madrid, Luxemburg, Vienna, Prague, Warsaw, Budapest, Chisinau, Bratislava, and other capitals.

In a new investigation, the Kyiv Independent attempted to uncover why these centers of Kremlin soft power often seem immune to sanctions and political concerns about Russian malign influence.

We found that the Russian Houses frequently exist in a legal gray area, shielded by diplomatic immunity and deliberate efforts to obfuscate their connection to the parent entity.

"I think it's never been recognized as a significant threat," Dmitry Valuev, president of the U.S. organization Russian America for Democracy in Russia, told the Kyiv Independent.

In Washington, several incidents have shown that “their activities are malign and damaging to the security and national interests of the United States,” he added, but this has only led American law enforcement to investigate specific individuals, not the organization itself.

According to the parent entity, Russian international cooperation agency Rossotrudnichestvo, Russian House currently has a presence in 71 countries around the world.

Staying afloat

On Feb. 13, the government of Moldova announced that it would be closing the Russian Center for Science and Culture in Chisinau.

The night before, Russian drones had violated the country’s airspace and struck its territory during an attack on Ukraine.

Moldova, which borders Ukraine, is no stranger to Russian aggression and influence. Since the early 1990s, the eastern part of its territory, known as Transnistria, has been occupied by an unrecognized separatist statelet backed by Moscow.

But, almost four months after the Moldovan government’s announcement, Russian House continues to conduct business as usual in Chisinau.

The reasons behind this highlight how difficult it can be to shut down Russian Houses, even when a government appears committed to doing so.

Legally, the Russian Centers for Science and Culture are something of a mystery.

They operate globally based on intergovernmental agreements signed between Russia and the host country. Each document differs slightly, but the general model allows each signatory to establish a cultural and scientific center in the other country.

Despite that official foundation, Russian Houses regularly lack local registration as legal entities. Their directors are often employed at the local Russian embassy, which grants them diplomatic immunity.

As a result, one won’t find the Russian Center for Science and Culture in Chisinau officially registered in Moldova. The same goes for the centers in Berlin and Washington.

The now defunct Russian House in Kyiv also never had legal registration — despite the fact that the Ukraine-Russia intergovernmental agreement, signed in 1998, explicitly required Russia to legally register the center in Ukraine. (At least in some places, including in Berlin and Washington, D.C., the buildings used by Russian House belong directly to the Russian government).

Today, that lack of registration allows Russian Houses to deny that they have a connection to parent entity Rossotrudnichestvo, which the EU sanctioned in 2022 as a conduit for Kremlin influence and propaganda abroad.

“In the European Union there are no representative offices of Rossotrudnichestvo, but (there are) independently operating cultural centers — Russian Houses,” Rossotrudnichestvo head Yevgeny Primakov told Russian state information agency TASS in May 2024.

But the connection between the two entities is not difficult to find.

Prior to the EU sanctions, the websites of the Russian Houses in Berlin and Paris each listed Rossotrudnichestvo as their parent organization. An archived version of the Washington center’s website from July 2022 states that it is “subordinate” to the agency.

Moreover, Rossotrudnichestvo is explicitly mentioned in bilateral agreements as an organization that oversees and ensures the operation of Russian Houses. Such language was included in the agreement signed between Russia and Germany. The agreement with Moldova is similar, but lists a previous name of the parent agency.

European sanctions froze all assets owned by Rossotrudnichestvo inside the EU and banned any financial or economic support for the organization. As representative offices of Rossotrudnichestvo, Russian Houses would presumably be unable to operate or cover their expenses within the EU.

Instead, many of them continue to operate, insisting they are “independent.”

The centers’ lack of registration also raises another question: Do they have official bank accounts or do they make payments in cash off the books?

In 2016, when Russian House still operated in Kyiv, Ukrainian journalists inquired about its status with the Ukrainian State Fiscal Service. But the tax authorities were unable to find any official bank accounts for the organization inside Ukraine.

A rare description of how Russian House carries out financial transactions came from Pavel Izvolsky, the head of the center in Berlin. It was still quite vague.

“We have certain procedures for processing online payments,” he told Deutsche Welle in 2023.

Currently, sanctions make it exceedingly difficult for Russia to conduct bank transactions with EU and U.S. entities.

In a written response to the Kyiv Independent, Olof Gill, spokesperson for the European Commission’s financial services department, said that EU Member States are responsible for implementing sanctions, identifying breaches, and imposing penalties through their national authorities.

Gill did not comment on whether Rossotrudnichestvo’s continued connection to Russian House constitutes a sanctions violation.

Nadia Koval, co-author of a Ukrainian Institute study on Rossotrudnichestvo, told the Kyiv Independent that sanctions can restrict Russian House’s ability to make payments and cooperate with local organizations. But that has its limits.

“Tough action by the host countries is required,” she said.

Diplomatic immunity and Russian espionage

In 2023, after the EU imposed sanctions on Rossotrudnichestvo, the Berlin public prosecutor’s office attempted just that kind of "tough action."

It launched a criminal probe to determine whether Russian House’s activities violated the German Foreign Trade and Payments Act.

But prosecutors were forced to close the investigation into Izvolsky — the Russian House director had diplomatic immunity.

That abortive attempt at reining in the center emphasized another aspect of Russian House: its ties to the embassy.

According to bilateral agreements, Rossotrudnichestvo is not the only organization supervising it. The Russian diplomatic mission also plays a key role.

It’s a common practice for the heads of the Russian Houses to be employed at the Russian embassy. Their deputies can also be diplomats, according to the agreements with Moldova, Germany, and the U.S.

That means diplomatic immunity protects them from arrest and prosecution in the host country.

Dr. Patrick Heinemann, a German lawyer specializing in constitutional law, told the Kyiv Independent that a broader criminal investigation into the center nonetheless continues, and it may focus on the activities of other Russian House employees, as well as third parties doing business with it.

Heinemann also noted that Germany’s new Central Office for Sanctions Enforcement is conducting a parallel investigation into Russian House under regulatory law.

“However, nothing about these investigations is being made public,” he said. “The authorities are evading press inquiries on the grounds that the investigations must not be jeopardized.”

Diplomatic immunity can also facilitate espionage activities, and employees of Russian Houses in multiple countries have fallen under suspicion of working for Russian intelligence agencies.

That happened twice at Russian House in Washington, D.C.

In 2018, the Trump administration expelled Oleg Zhiganov, then the director of the Russian Cultural Center in Washington, D.C. The U.S. government said he was an intelligence officer operating under diplomatic cover and part of a group that engaged in “aggressive intelligence collection.”

His predecessor, Yury Zaytsev, apparently also came under suspicion. U.S. media reported that the FBI determined he was involved in compiling dossiers on Americans who took part in cultural exchange trips to Russia and could later be cultivated as intelligence assets.

He reportedly left the U.S. after the FBI investigation started.

It didn’t stop his diplomatic work. Zaytsev became director of the Russian House in Nicosia and later held the same position in Vienna.

That wasn’t the only instance in which Russia House was implicated in espionage.

The Danish newspaper Information reported that Russian House in Copenhagen was a favored gathering place for Russian embassy employees later identified as spies. The cultural center built close ties with Danish research institutions, most notably with the Technical University of Denmark (DTU). It even hosted joint conferences, seminars, and other events with the university, Information reported.

Aleksey Nikiforov, a DTU researcher who frequently attended Russian House events, was later sentenced to three years in prison for, among other things, collecting intelligence on green technology from DTU and SerEnergy, a company based in Denmark’s far north. Prosecutors said he passed the information on to a Russian intelligence service in exchange for payment.

The independent Russian investigative outlet The Insider has also reported that the head of Russian House in Berlin Pavel Izvolsky was once registered as residing in a dormitory of the Moscow Higher Military Command School (MVVKU), an institution known for training cadets for the SVR and the GRU, another Russian intelligence agency.

Izvolsky did not respond to requests for comment.

In Moldova, the fate of Russian House still in the air

To halt the activities of the Russian House in Chisinau, Moldova decided to terminate the intergovernmental agreement with Russia that allows the Russian Cultural Center to operate in the country.

"Once the termination procedures are completed, the Russian Cultural Center will cease its activities in our country," the Moldovan foreign ministry said in a statement.

But ending the agreement has taken a while.

The Moldovan culture ministry told the Kyiv Independent that it had prepared draft legislation to terminate the agreement and it was now up to Parliament to pass it. But the bill has not yet been put to a vote.

Dragos Galbur, head of the National Moldavian Party (PNM), has been calling for the center’s closure for over two years. He warns that it serves as a tool for Russification and propaganda within Moldova, similar to the tactics Russia employed in Ukraine.

Galbur notes that, as long as there is no parliamentary decision, the Russian House in Moldova continues to hold events in the country.

“They go into schools, hold these bizarre so-called ‘open lessons’ with kids, telling them Russia is Moldova’s friend, that the Soviet Union was a great power, and that we’re all its children,” he told the Kyiv Independent.

Galbur believes Parliament could have resolved the issue swiftly. With today’s pro-European majority, “they could vote in 15 minutes”, he said.

But he thinks they fear backlash from pro-Russian voters — an important electoral group ahead of the September 2025 parliamentary elections.

A lack of political will may also explain why some EU countries have failed to close down Russian Houses.

According to Deutsche Welle, the German authorities may fear that the Russian government could retaliate by closing the Goethe Center in Russia. German lawyer Heinemann, who is well acquainted with the case, also believes this explanation.

He notes that, although Russian House directors enjoy diplomatic immunity, they can still be declared persona non grata and expelled from Germany if they commit a criminal offense. But that has not happened to the Russian House director in Berlin.

Creative solutions

Not all countries have hesitated to close down Russian Houses. Several — including EU members — have taken decisive action.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Denmark, the UK, Romania, and Azerbaijan have all shut down or suspended the operations of their Russian Houses.

Notably, none of these moves appear to be directly based on EU sanctions against Rossotrudnichestvo. Instead, the countries have gotten creative.

In Denmark, authorities initially tried to freeze Russian House’s funds. But that didn’t stop its activities. The Center finally closed its doors after the Danish government expelled five Russian diplomats and 20 embassy administrative staff from the country.

While their names have never been made public, the Russian House director was presumably among them.

“They forced us to leave,” the Сenter wrote in its final Facebook post, noting that Russian House cannot operate without a director.

Romania acted similarly. In early 2023, the Romanian foreign ministry set a six-months deadline for Russian House in Bucharest to shut down. A few weeks before the deadline, Romania expelled 40 Russian embassy staff, forcing Russian House to suspend its operations.

(A similar tactic failed in Moldova. In August 2023, Moldova expelled the head of the Russian House in Chisinau along with 44 Russian diplomats, after The Insider reported on an espionage case involving antennas mounted on the roof of the Russian Embassy. Shortly thereafter, Russia replaced him with a new acting director Artyom Naumenkov and Russian House continued its work.

The Kyiv Independent tried to contact Naumenkov, but he declined our call, did not respond to the written questions and later hid his profile photos on Telegram.)

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan swiftly shuttered the Russian House in Baku after a Russian air defense system shot down an Azerbaijani passenger plane, killing 38 people.

Amid deteriorating relations with Moscow, the Azerbaijani foreign ministry used the fact that Russian House was not registered as a legal entity to demand that it cease operations. Azerbaijan also required the center to vacate its building within a month and a half because the property was set to be sold.

The Russian House in London simply never reopened after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The Rossotrudnichestvo representative in the U.K. was denied a visa, leaving the сenter inactive.

In Ukraine, efforts to close the Russian House in Kyiv were delayed for several years because Parliament needed to pass legislation terminating the intergovernmental agreement with Russia.

Finally, in 2021, the government imposed sanctions on Rossotrudnichestvo. That shut down the center’s activities without a parliamentary decision.

But unlike Ukraine and many countries in Europe, the U.S. has not closed down Russian House or imposed sanctions on Rossotrudnichestvo. After a 1.5-year pause, the Russian Cultural Center in Washington resumed its activities in December 2022.

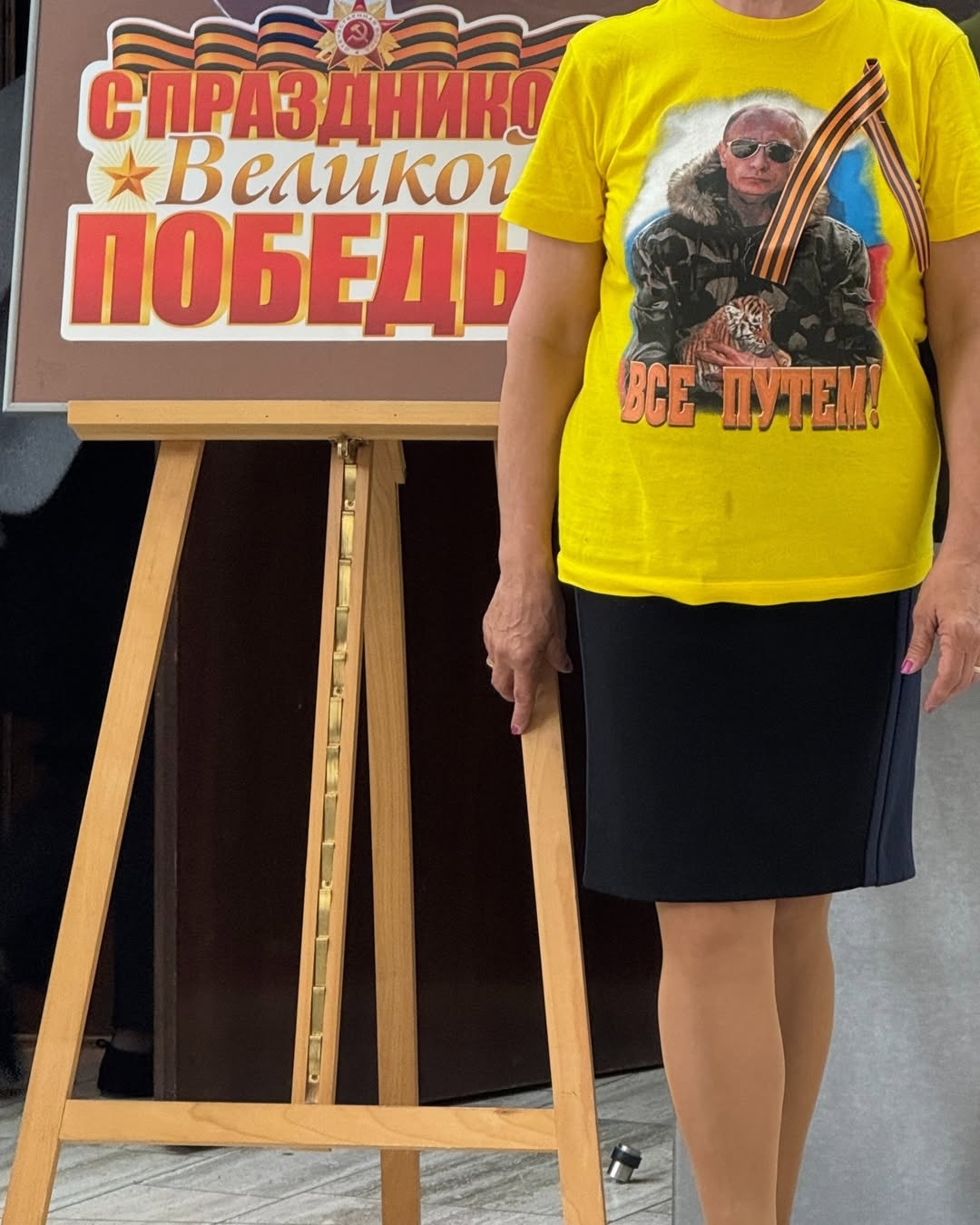

The center had no issue holding celebrations marking the anniversary of Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and has done so twice since 2022.

It continues to demonstratively glorify Russian military aggression while the Trump administration tries to negotiate peace. While some of its visitors are members of the Russian diaspora, its events also attract Americans without connections to Russia.

They include a handful of highly involved Americans from business, cultural circles, and academia, as well as philanthropists — some of whom were among the first to sponsor the Russian House at the time of its founding. They also formed the nonprofit Friends of the Russian Cultural Center to help raise funds for the Russian House and support the building’s renovation in the late 1990s.

Supporters of the center have portrayed it as a benign cultural initiative aimed at promoting understanding between Russians and Americans. But not everyone agrees.

Activist Valuev says that the Russian Cultural Center’s main goals include building connections and shaping U.S. public opinion in favor of the Kremlin.

“Businesses, religious groups, churches, cultural programs, education, exchange programs — all of it is used and weaponized by the Russian government,” he said. “It’s not a question of whether they use it. They do.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Linda, the author of this piece. I hope it sheds light on how Russian cultural diplomacy operates in the U.S. and Europe — and why understanding soft power tools matters.

If you’d like to support our reporting, please consider becoming a member of The Kyiv Independent.