Can Ukraine survive without the US — and can Europe fill the gap?

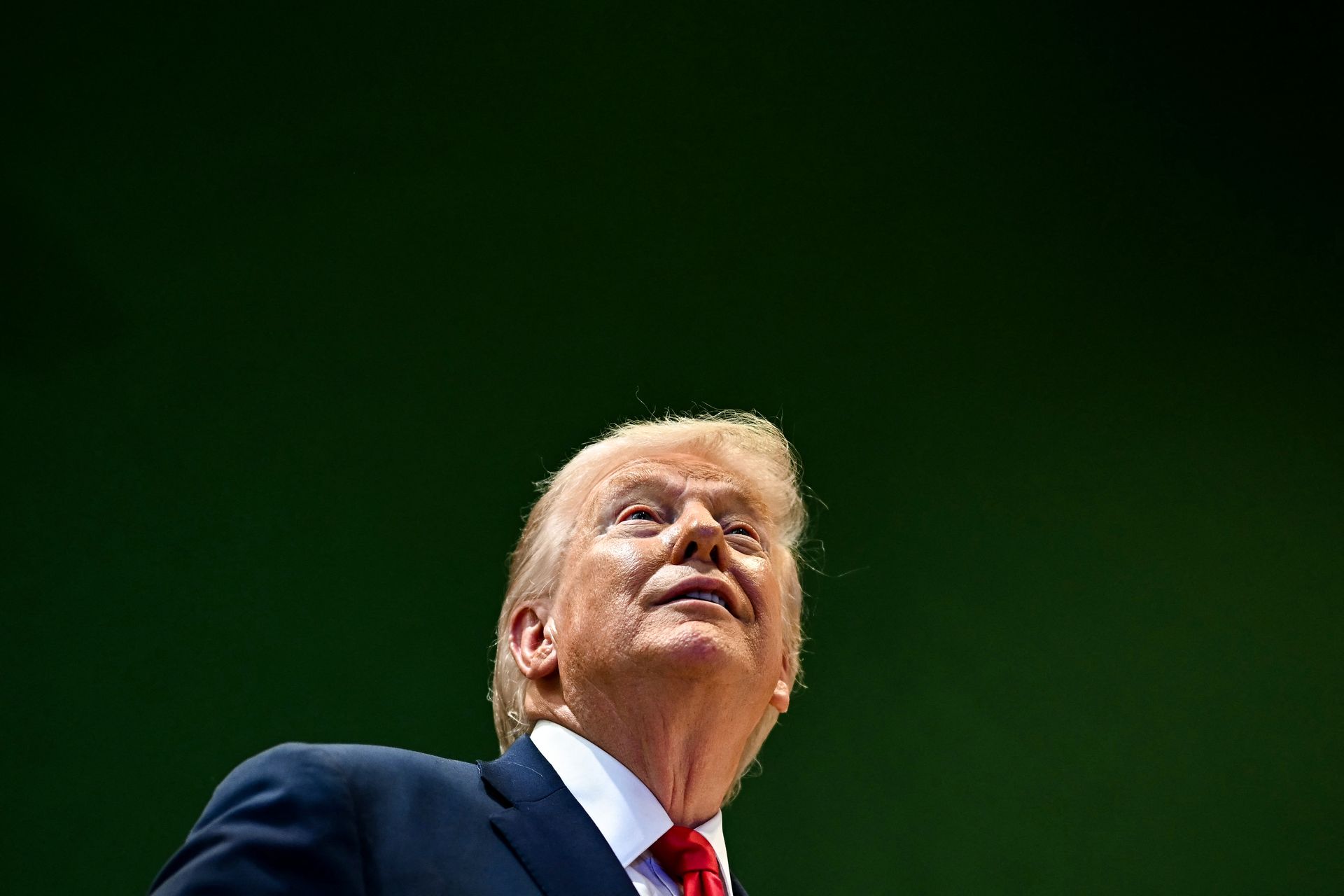

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks alongside President Volodymyr Zelensky during a news conference following their meeting at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago club on Dec. 28, 2025 in Palm Beach, Florida. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Since Donald Trump's return to office, Kyiv and its European allies have shared one overriding fear: a full U.S. withdrawal from the war effort.

Washington remains a supplier of hard-to-replace military hardware — paid for by European allies or allocated by the previous administration — and vital intelligence assistance, helping Ukraine to defend its skies and strike deep behind Russian lines.

But as Trump's attention might soon pivot to the midterm elections at home, or be swayed by Russia's generous business deals, Ukraine and Europe must treat the U.S. exit as a real possibility.

The U.S. president's previous pauses in military assistance to Ukraine and his aggressive bid for Greenland — a sovereign territory of a NATO ally – convinced many that he is not a reliable ally.

A full halt in U.S. support would not mean an immediate defeat for Ukraine, says Mark Cancian, a retired U.S. Marine colonel and a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank.

It might, however, "strengthen Russia in its belief that time is on its side, that they can just wait and keep fighting and eventually, the Ukrainians will collapse."

What assistance does the US still provide?

Despite Trump's pledge not to spend any more U.S. money on Ukraine's defense, the American support has not fully ceased.

He has mostly let continue assistance allocated by the Biden administration, including already approved presidential drawdown authority (PDA) packages — drawn from U.S. stocks — and the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI), which sources new weapons from American contractors.

As of mid-2025, the U.S. was still set to deliver around $30 billion worth of military assistance already allocated by the previous administration over the next three-and-a-half years, CSIS analysts calculated.

A new defense spending bill signed by Trump in December also included $800 million in USAI funding through 2028.

There is also a broad array of intelligence support, from signals intelligence (SIGINT) to human intelligence, which has enabled the Ukrainian forces to carry out long-range precision strikes — including against Russian oil refineries last year.

Finally, the Prioritized Ukraine Requirements List (PURL) scheme allows NATO allies to purchase critically needed weapons for Ukraine directly from U.S. stocks, namely, the equipment that Europeans would struggle to provide themselves.

Cancian, the CSIS analyst, underscored air defense — namely, the Patriot systems — and anti-drone systems as areas where Europe still lags behind the U.S.

Washington also holds leverage over third-party donations involving American technology, such as F-16 supplies provided by European allies.

"About 75% of all missiles for Patriot systems and nearly 90% of missiles for other air defense systems that Ukraine has received recently were supplied specifically through PURL," says Yehor Cherniev, a deputy chairman of the parliament's national security and defense committee.

"At the same time, the program also reduces the political risks we used to face when receiving weapons from the U.S. as aid," the lawmaker told the Kyiv Independent.

But there are vulnerabilities in this system — both on the American and the European side.

"If you're going to buy existing equipment, that will divert it from U.S. stocks," Cancian told the Kyiv Independent.

But such a move must go through a round of approvals in the Pentagon, where it could face opposition from players like Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby, he added.

Colby, a protege of Vice President JD Vance, was the man responsible for previous disruptions in U.S. aid flowing to Ukraine.

Yet, the other alternative — ordering weapons from U.S. manufacturers — is not practical either, as completing new contracts can take years, and the Pentagon pivots toward replenishing its own arsenals, used up in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Europe stepping up

There is also the question of how deep into their pockets the Europeans are willing to go.

The PURL initiative raised over $4 billion between August and December 2025, but Ukraine said it needs more than three times that amount this year.

President Volodymyr Zelensky even directly accused Europe of failing to pay for a PURL package on time, leading to delays in U.S. missile deliveries amid Russian attacks against the Ukrainian power grid.

"(PURL) is effective. The main question is the amount of money that can be raised to finance it," Cherniev says. "There definitely needs to be more — and we are working on that."

Despite Ukraine's current criticism, European military assistance rose sharply in 2025, driven by concerns about Trump's foreign policy shifts.

Earlier in the war, the U.S. could simply provide more arms because European arsenals were poorly stocked. However, the European defense industry has grown rapidly in recent years, rising by 13.8% year-on-year in 2024.

The EU introduced new instruments, such as the 150-billion-euro ($180-billion) SAFE (Security Action for Europe) program, which offers loans to member states to bolster their defenses or provide additional support to Ukraine.

By June 2025, Europe had overtaken the U.S. as Ukraine's leading military backer, allocating 72 billion euros ($85 billion) since 2022, compared with 65 billion euros ($77 billion) from the U.S., according to the Kiel Institute.

Not every European nation has been as generous. Germany, the Nordic and Baltic states, or the Netherlands have committed significantly more resources, while Italy and Spain — despite being among Europe's largest economies — have contributed relatively less.

The latest Kiel Institute report showed that last year's assistance level remained "relatively stable," as the halt in new U.S. allocations was offset by a 67% hike in European military aid — a development driven primarily by London, Berlin, and Northern Europe.

According to the paper, the 2025 military allocations were nevertheless 13% below the annual average in 2022-2024, amounting to a little over 30 billion euros.

However, Ukraine said that overall, it had attracted $45 billion in international security assistance last year — a figure that also includes defense investments, training, and logistical support — which is more than any year since the outbreak of the full-scale war.

Jan Kallberg, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), argues that Europe can — and should — accept even deeper drawdowns from its own stockpiles.

According to the expert, the European push to offset the declining U.S. support has been slow so far — but these "efforts will increase radically and be far more tangible in the years to come as the new reality sinks in."

Bracing for the US exit

After the U.S. briefly paused intelligence support for Ukraine following Trump's heated meeting with Zelensky, Europeans have sought to remove this vulnerability.

As of January, France is providing two-thirds of intelligence support to Ukraine, French President Emmanuel Macron said. An undisclosed Western official told the Financial Times that Ukraine's reliance on U.S. intelligence could be "largely reduced within months."

France possesses one of the most sophisticated intelligence services among the powers of its size, according to Kallberg. But even Paris, he warned, lacks the scale to "fully offset the loss of U.S. capabilities" in backing Ukraine.

Ukraine is also pivoting toward European hardware to shore up its air defenses. In 2026, it is set to receive the first next-generation SAMP/T system, with the Air Force expected to follow up by acquiring 100 French Rafale fighters and 150 Swedish Gripens over the coming years.

Finally, Ukraine has been ramping up its own defense production, from Bohdana and Marta artillery, through Neptune cruise missiles and Sapsan ballistic missiles, to millions of drones of various models.

Kyiv has also sought to convince Western defense companies to set up shop in Ukraine, with German arms giant Rheinmetall opening a plant for vehicle repair and production in 2024 — the first of the four factories the company plans to open in Ukraine.

More than half of the weapons fielded by Ukraine's military were domestically made by the end of last year, Prime Minister Yuliia Svyrydenko said, with that share set to rise further.

The obstacle, however, is cash. Speaking at an event, Cherniev said that the Ukrainian defense industry can produce military hardware worth $35-$40 billion per year — but the state budget lacks the necessary funds.

According to the lawmaker, Ukraine aims to cover roughly half of the production costs, while the other half would be financed by international partners.

No matter the next steps by the Trump administration, it is clear that Europe now plays a critical role in keeping Ukraine in the fight — both with arms and money.

Abbey Fenbert contributed additional reporting to this story.

read also