Burning horizon: As Russia makes gains near Pokrovsk, civilians remain frozen in inaction

With residents caught off guard by the speed of Moscow’s advances, the traditional dilemma of whether to evacuate or not is made all the more painful.

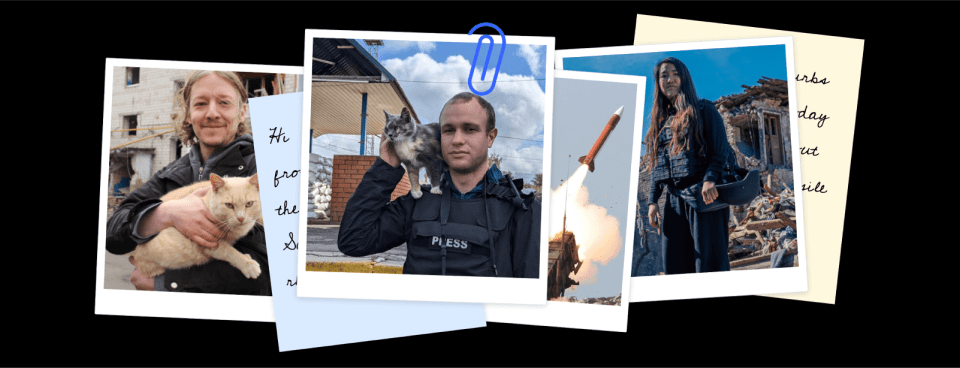

Residents look at the burned remains of a house after a Russian glide bomb strike in Pokrovsk, Donetsk Oblast, on Sept. 9, 2024. (Francis Farrell/The Kyiv Independent)

SELYDOVE, Donetsk Oblast – “Kostia! Kostia?”

Despite their volume, the volunteer’s calls dissipate in the strong winds coursing through the central streets of Selydove.

This is the most dangerous part of any evacuation operation in a front-line city: making visual contact with civilians who have agreed to leave.

Russian soldiers are only about one and a half kilometers away from these streets, putting anything that moves around here, people or vehicles, military or civilian, a potential target for a Russian shell or drone.

The skies on this warm autumn morning are clear, putting everything in view of Russian eyes in the sky; the only consolation is the strong breeze, which might cause problems for the drone pilots.

With no telephone or mobile connection, these rendezvous are organized by word of mouth or the occasional phone call that gets through, and it is rare that everything goes to plan.

This time, Kostiantyn, who evacuation volunteer Serhii had agreed to pick up at this time and location, is nowhere to be found.

A key urban milestone in Moscow’s offensive towards the key strategic city of Pokrovsk, Selydove saw Russian forces close the distance to its outskirts in a matter of a couple of weeks over August.

As of early October, this mining city with a population of about 21,000 before the full-scale invasion looks now to become the latest in a series of “fortress” cities in Donetsk Oblast, urban and industrial areas where Ukrainian forces have made a frantic defensive stand.

Throughout this summer and continuing into autumn, Russia has consistently focused offensive efforts on the southern half of the remainder of Ukrainian-controlled Donetsk Oblast.

After first making a beeline for the city of Pokrovsk itself, the offensive slowed in early September, instead turning south in an attempt to cut off a large group of Ukrainian forces.

In contrast to most other front-line cities, many buildings, even windows, were still more or less intact in Selydove, a testament to the speed and recency with which the fighting arrived here.

This speed, this rapid transformation of a city from sleepy mining town to active battle zone, inevitably caught many of the civilians in Selydove unprepared.

As Russian forces begin their time-honored tradition of raising a city to the ground before assaulting the ruins, local police no longer enters the city, while fewer and fewer volunteers are willing to help evacuate the locals in fear of drone attacks.

Those civilians who have remained now find themselves in a world where all life in Selydove is being snuffed out bit by bit, and questions of life and death can be decided in an instant.

Close shave

Parking his car under a tree, Serhii ponders his next move, periodically calling out for Kostiantyn.

This isn’t unusual: anything could have changed for local civilians since last making contact with volunteers: spontaneous decisions or split-second tragedies can change things in an instant, and if the volunteer can’t find the person quickly, it’s best to move on before they themselves become a target.

Serhii, 36, who himself hails from Donetsk Oblast and declined to give his last name because of concerns for his contacts in the occupied territories, has evacuated dozens of people from some of the hottest parts of the front line since the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

Suddenly, an old Lada crawls past along the street: in it, two large shirtless men and a younger woman in the back.

Serhii flags the locals down, asking if they know Kostiantyn and where he might be.

After a short conversation, he jumps into the back without a second thought, promising to be back within about fifteen minutes.

Selydove seems quiet as that time passes, but not for long: one after the other, two Russian glide bombs fall within a few hundred meters.

Carried by the breeze between the high-rise apartments, the dust that soon flows around the city carries the unmistakable smell of gunpowder.

Tension builds as time passes, before it is broken by the return of the same Lada down the central street, only this time, something is clearly wrong.

There is no sign of Serhii, and instead of him, the locals have tied a cow to the back of the car, ambling down the road at an absurdly slow pace.

“He got out back there, two blocks down,” one of them says, pointing down the central street, right in the direction of Russian forces.

“But careful, where he got out was right where the bombs landed later.”

Walking in that direction and expecting the worst, Serhii emerges onto the road with a stubborn frown on his face, covered in dust and with a heavy cardboard box in each hand.

To call it a close call is putting it lightly; according to Serhii, one of the glide bombs had landed just two houses away from him, causing plaster and glass to come down on top of him.

With him is Kostiantyn Krutskykh 39, and his father, 72-year-old Oleksandr.

The father-and-son pair had already fled once, from the town of Kurakhivka further south, which has seen even heavier fighting than Selydove, though is still held by Ukrainian forces.

Living on a prayer

As the group gathers all its things and makes its way back to the van, a drone passes low over the heads of Kostiantyn and his father.

With a high-pitched whir sounding neither like a typical FPV (first-person view) drone nor like a DJI reconnaissance version, the quadcopter takes a quick look at the party before flying off in the direction of Russian forces.

“Kamikaze drones are flying every day here,” said Oleksandr.

Over several hours spent in Selydove, dozens of civilians could be seen wandering the city streets, usually alone or in pairs.

Often looking to gather water, food, or firewood, the residents stroll with a calm gait, seemingly oblivious to the constant danger of death from above.

With the arrival of strangers, some approach Serhii to ask about evacuation, or in one case, just for a cigarette.

Residents often hope the volunteers will help evacuate pets, livestock and heavy personal belongings – requests that often don’t match what people like Serhii are willing to risk their lives for.

“People are holding on to their property, but even when they lose most of it, they cling to whatever is left,” said Serhii.

“By the time they change their minds, there is often nobody left to bring them out.”

Sitting in the sun on an ancient Soviet sidecar motorcycle, 58-year-old Volodymyr combs his streaky gray beard as he contemplates his next move.

“I was reading about it in the weeks before on the internet, that there was an offensive ongoing and so on,” he said, “but it didn't seem that bad.”

Volodymyr said he was warming to the idea of leaving, but the retired miner still had his doubts.

“I need a phone connection so I can call my relatives... I need petrol, maybe I can get to Pokrovsk with this but then what next? Leave, where can I leave?”

Asked how he understood the war that had come to his doorstep, he paused before answering.

“If there was peace here and people could live…” he said.

“I lived my whole life here, what kind of position can I have towards the bombing, towards the burning houses of my neighbors?”

Serhii’s second-to-last stop is at a nearby Orthodox church, a little further from the front line, where one more person had left a request to evacuate.

Once again, nobody is waiting at the rendezvous point, so Oleksandr looks inside the church, where his family used to go before he moved to Kurakhivka.

At a cramped table in the entrance room, three middle-aged women sit with a pen and paper in hand, scrawling away at long passages of texts.

“We are copying out prayers,” said one of the women, surprised that it might be seen as a strange activity.”

“When there is shooting and it is scary,” continued another of the women, 64-year-old Valentyna, “we think that reading a prayer like this, God and the Virgin are protecting us.”

The person Serhii and Oleksandr were looking to find had gone days ago, the women said.

Saying farewell to Oleksandr with a tearful embrace, Valentyna rejoins the other women in writing her prayers.

Future in limbo

Compared to Selydove, the city of Pokrovsk seems like a haven.

Explosions can be heard regularly in the distance, but it is clear that they come from battles in the vast fields southeast of the city, where Russian forces continue to make incremental gains despite fierce Ukrainian resistance.

Largely empty as they are, the streets and public spaces are still mostly intact; flower beds full of roses, the symbol of Donetsk Oblast, are in full bloom, taken care of by local municipal workers until the very end.

Once the pride of modern Pokrovsk, the Bulvar shopping complex, where Ukrainian soldiers and civilians alike would sip flat whites and eat avocado toast in a comfortable trendy interior just a month earlier, has been closed and boarded up.

This is what 10 kilometers from Russian positions looks like: just far enough for most of the urban area to be outside the range of tubed artillery fire and suicide drones, and in turn, just far enough for some semblance of normal life to continue.

But for the foreseeable future, life in Pokrovsk will be anything but normal, and local authorities here are doing their best to make it clear.

As of late August, the official curfew was extended to 20 hours, from 3 p.m. to 11 a.m. in the morning.

Meanwhile, complementing the large billboards emblazoned with the single word “Evacuation” all over the city, police cars conduct constant laps of the city streets with loudspeakers reminding the remaining residents of the need to pick up and leave.

Likely in an effort to hamper Ukrainian military logistics in the area, all three main road bridges in the city were also destroyed by Russian forces in the first weeks of September.

Several people who spoke to the Kyiv Independent in central Pokrovsk had already made the decision to leave, and were using this precious time in relative safety to gather their belongings and prepare.

“We didn't think that the war would come to Pokrovsk,” said 50-year-old Liudmyla as she filled a dozen water bottles at a drinking water distribution point before leaving the next day.

“We can hear that artillery is beginning to reach the city. That's when things start getting really dangerous.”

Hailing from a village outside now-occupied Volnovakha further south in Donetsk Oblast, Liudmyla took her family first to occupied Donetsk, before making the difficult journey back to Ukrainian-held territory.

Still, in a practice that is common with internally displaced people in Ukraine, her family chose not to move too far from home, despite the chance that the war would come knocking again.

“I want to go home, to my own bed,” she said.

“But the most important thing is that everyone is alive. There are good people everywhere... well, maybe more bad people now that there is war.”

As quiet as it is during the day in Pokrovsk however, the coming of night brings with it danger and destruction.

Driving down a quiet row of residential houses, the color palette on the street makes a sharp jump from autumn greens and browns to dark gray and black.

The smoldering ruins of three residential houses mark the spot where a Russian glide bomb struck late the previous evening.

One resident, a middle-aged man who was at home during the strike, sits despondently in front of what is left of his house, having miraculously made it out with just a few light scratches and burns.

Firmly declining to speak about the ordeal, the man remains waiting for friends to pick him up before they go to file for government compensation.

In the house opposite, which burned down in the hours after the strike 72-year-old coal miner Anatolii Firsov, who has lived in Pokrovsk all his life, searches through the remains of the house, doing his best to salvage the belongings of his friends, who also survived the attack but were taken to hospital with more serious wounds.

“There is nowhere to live anywhere,” he said.

“People are leaving Kharkiv, Sumy, from here, where are they all going to live? Donbas was always the most densely-populated part of Ukraine.”

As he loads what he can save into his old car, including his friend’s playful young tabby cat, Firsov tries to maintain an upbeat attitude.

“Of course I hope I will be able to stay, I hope everything stabilizes, and everything returns to its place, and it will be alright.”

But with no end to the Russian offensive in sight, and with countless examples of the fate of those cities caught in its path, the grim prospects for his future here are hard to deny.

“Even if I wanted to live under occupation, what would be the point if everything is going to look like this?” he said.

“Of course I am considering all options. Once I see the whole horizon burning, I will get in my car and leave, wherever my eyes take me.”

Watch the video version of this story on the Kyiv Independent's YouTube channel:

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Francis Farrell, cheers for reading this article. This is the second of three stories that we will publish from our field trip to the Pokrovsk direction at one of the most critical times for the Ukrainian defense of Donbas since the start of this war. Whatever happens and however it is presented in the world's media, we see it as our job to bring you the reality from the ground in its most raw and honest form. Please consider supporting our reporting.