After release from captivity, Russian POWs often 'sent back to die' in Ukraine

Russian prisoners of war in a Ukrainian prison in western Ukraine on April 18, 2023, amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. (Diego Herrera Carcedo / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

For Ukrainian prisoners of war (POWs), release from captivity can feel like escaping hell. But for Russian POWs, it might mean walking straight into another.

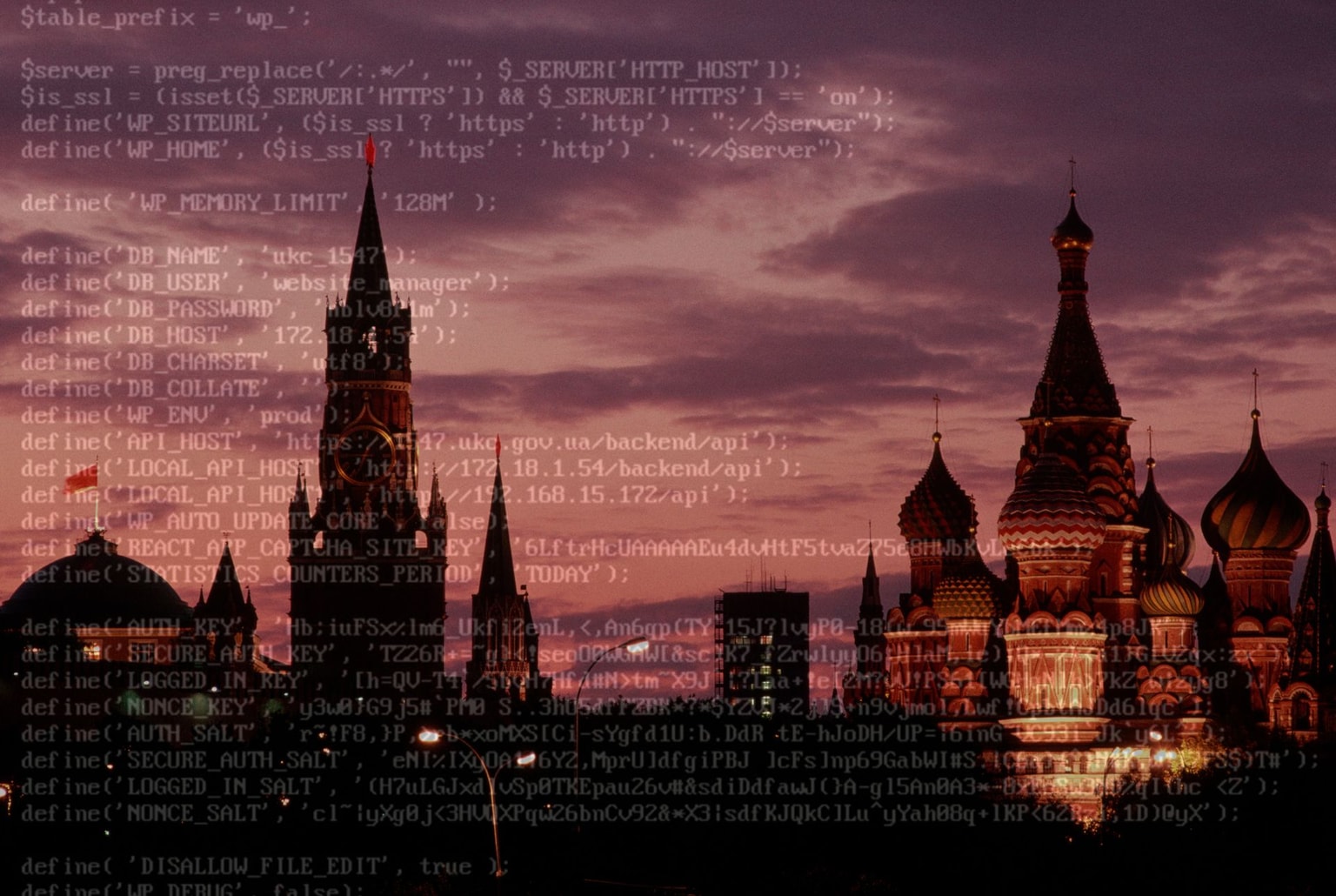

Lengthy interrogations by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), criminal prosecution, and forced return to the front line are often what await Russian POWs after they return home, despite efforts from the Kremlin to disguise it.

"(Russian) propagandists film videos where the released POWs appear to be having fun on cue. But we understand this is all just a facade," Petro Yatsenko, spokesperson for the Ukrainian Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, told the Kyiv Independent.

"They are being sent back to die and invade a foreign land," he says. "Their return home is nothing like the return of our men and women," he says.

In early June, the independent Russian media outlet Novaya Gazeta Europe reported, citing the human rights group "Idite Lesom," that Russian POWs returned in the largest 1,000-for-1,000 prisoner exchange in May were sent back to their military units and could potentially be redeployed to the front lines in Ukraine.

"Relatives of the soldiers have repeatedly said that after the exchange, they were not even allowed to see their loved ones; men, including the wounded, were simply sent straight to the front lines," Novaya Gazeta wrote.

Prisoner swaps have remained one of the few active channels of communication between Ukraine and Russia, even after Kyiv severed diplomatic ties with Moscow in 2022.

As of late July, Ukraine has secured the return of more than 5,857 individuals — both soldiers and civilians — through more than 65 prisoner exchanges since Feb. 24, 2022.

Russia, however, does not publicly disclose the number of POWs returned from Ukrainian captivity. In 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that approximately 1,350 Russian soldiers remained in Ukrainian captivity.

Details about Russian POWs who return from Ukrainian captivity are typically kept under wraps as Russia rarely reveals who they are, referring only in general terms to servicemen from specific regions.

The lack of transparency continues after their return, as the public is given virtually no insight into what becomes of them.

Different conditions

Ukrainian and Russian POWs face vastly different realities in captivity and upon their return.

In Ukraine, Russian POWs are primarily held in five specialized camps set up after the start of the full-scale invasion. Representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations, as well as journalists, have access to Russian POWs and the facilities where they're held.

The inspections by ICRC take place every two months and can last several days, Yatsenko told the Kyiv Independent earlier in June.

In Russia, there are no specialized camps for Ukrainian POWs outlined by the Third Geneva Convention. Instead, captured soldiers and civilians are held in more than 180 detention sites across the country, according to Yatsenko.

While there are no credible reports of Russian POWs being tortured in captivity, Ukrainian POWs are routinely subjected to torture and inhumane treatment while in Russia.

Upon their return home, Russian POWs usually do not require rehabilitation or medical assistance, unlike Ukrainian POWs, many of whom come back severely underweight and suffering from serious health issues.

Fake celebration

When Ukrainian POWs call their relatives upon release it's often the first contact they've had with them during captivity due to Russia cutting off nearly all outside communications, leading to emotional scenes that have been repeated throughout the war.

Russian POWs, on the other hand, are allowed to call home while in captivity. When released, they often appear lost and try not to say much while being filmed by Russian propaganda channels.

Yatsenko says that Russia has only recently begun staging these celebratory welcome moments for its released POWs.

Upon their return, Russian soldiers are often judged by society for being captured rather than dying in battle.

"Russians copy everything we do," he says. "We greeted our people with flags, joy, and hugs. It is such a deeply touching, informal ceremony."

"But Russians (POWs) were quietly taken away without any celebration. It's clear they noticed this, and their side's reception was dark and somber. Now, it seems they have decided to put on a forced, staged celebration of their own," Yatsenko says.

Yatsenko says the released Russian prisoners are also interrogated by Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) officers.

"All of them (released Russian prisoners) are taken for interrogation by the FSB," Yatsenko says.

"There is a military facility in Moscow where all of them are transported. They spend two, sometimes three weeks there undergoing questioning," he added.

Guilty of surrender

Upon their return, Russian soldiers are often judged by society for being captured rather than dying in battle.

In late May, Russian military blogger and war propagandist Aleksandr Sladkov wrote on Telegram that the return of captured pro-Russian political prisoners "should be publicized," but when it comes to Russian soldiers captured by Ukraine, "there's no need for pomp."

"Being taken prisoner is not exactly an act of valor in this 'special military operation,'" he wrote.

"Wounded soldiers returning from hospitals — sure, welcome them with ceremony. POWs should be cared for, but not turned into heroes. The only exception is for those who fought to the bitter end and were captured unconscious."

Other military bloggers have also proposed sending released Russian POWs to filtration camps to determine who surrendered voluntarily, since under Russian law, voluntary surrender to captivity is punishable by imprisonment for three to ten years.

In early April, the Russian independent news outlet Meduza reported that Russian prosecutors are seeking a 16-year prison sentence for serviceman Roman Ivanishin in Russia's first-ever case prosecuting a soldier for 'voluntary' surrender to Ukrainian forces.

According to Meduza, Russian authorities opened a criminal case against Ivanishin upon his return home from captivity.

Back to the trenches

Numerous reports suggest that, upon their release from captivity, Russian troops are sent back to fight against Ukraine.

"This is quite a common practice," says Yatsenko. "Most Russian soldiers who return are of conscription age and still under active contracts, so they are sent back to the front lines."

Under current Russian law, there are no limitations on redeploying military personnel after their release from captivity. Therefore, a servicemember who returns from captivity can be assigned duties by their unit's leadership.

"There have been instances where the same Russian soldier was captured twice or died in combat," says Yatsenko. "Consequently, some recovered bodies have been identified as belonging to Russians who were previously held in our captivity."

Yatsenko says that even if a military contract expires while a soldier is in captivity, they will likely be compelled to sign a new one upon their return: "Many Russian POWs mistakenly believe otherwise while in captivity."

"Russia is in desperate need of manpower, and we see them sending troops to the front lines. This includes those who have not fully recovered from their injuries and even those on crutches," says Yatsenko.