Desperate for more soldiers, Russia recruits HIV-positive prisoners, civilians

Despite Russia's official claim that it does not conscript individuals with serious illnesses, recruitment efforts targeting people with HIV and hepatitis persist.

An advertising billboard in St. Petersburg, Russia, displays an image of a Russian military personnel urging individuals to sign a service contract with the Russian Defense Ministry on Jan. 18, 2024. (Artem Priakhin/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

The number of HIV and hepatitis cases among Russian soldiers is on the rise, as Moscow appears to be deliberately recruiting those sick — even encouraging their enlistment.

According to the report from Carnegie Politika, the number of HIV cases detected in the Russian armed forces increased 13 times by the end of 2022, and was 20 higher by the end of 2023, compared to the start of the all-out war.

Several factors are at play — blood transfusions for wounded soldiers, reusing syringes in field hospitals, and soldiers engaging in drug use and unprotected sex.

Under Russian law, people living with HIV, tuberculosis, or hepatitis C should be exempt from military service. Yet, since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, independent Russian media have reported that HIV-positive individuals continue to receive draft notices, either because military officials are unaware of their health status or because they simply don’t care.

To replenish military ranks, Russia is also recruiting prisoners with infectious diseases, as well as residents of Russian-occupied territories, who don't have the leeway to escape the draft.

Olga Romanova, an exiled Russian journalist and founder of the NGO Russia Behind Bars, said that there is effectively no formal mobilization process in Russia — instead, "everyone is being recruited."

"They basically take everyone indiscriminately," Romanova told the Kyiv Independent. "Because it's unofficially approved, because no one is planning to treat them at all," she continued.

"It's easier for everyone if they get killed there — no one will notice the difference."

Recruiting prisoners

Recruitment of HIV-positive Russian prisoners was first reported in 2022, carried out under the leadership of Yevgeny Prigozhin, then head of the Wagner Group militant formation.

Prisoners with HIV or hepatitis were marked with red or white bracelets, respectively. Some of them were captured by the Ukrainian army.

Four years into the full-scale war, recruitment from Russian prisons has only continued to rise, Romanova said.

According to her, prisoners are promised up to 200,000 rubles (about $2,500) a month to enlist — a large sum for them — but receive no access to medical care or treatment. Those payments are also frequently delayed or withheld entirely, she said.

Russian prisoners with HIV or hepatitis were marked with red or white bracelets, respectively. Some of them were captured by the Ukrainian army.

(Ukraine's military intelligence)

In many cases, prison doctors withheld care, believing the inmates were destined for the battlefield.

"There's no point in paying. If you're a stormtrooper, you've got an assault tomorrow or the day after," she said.

"I have the feeling that (Russian President Vladimir) Putin, including through this war, is solving the problem of disposing of excess people. And this is that very disposal."

"But the most important thing is the illusion of freedom. If you survive, you'll be free after the war," Romanova added.

In the fall of 2024, Ukraine's military intelligence (HUR) reported that Russia was forming assault units composed of people with hepatitis B and C to involve them in the war against Ukraine.

Russia has recruited at least 250,000 prisoners over three years of the all-out war, according to Romanova's conservative estimate, with 40% suffering from serious illnesses like HIV, tuberculosis, or hepatitis.

"In fact, they (imprisoned Russians) are used as cannon fodder and as a weapon," said Iryna Yakovets, legal advisor at 100% Life, the Ukrainian non-profit organization that advocates for and supports people living with HIV/AIDS.

"That is, they were sent into battle precisely because they are HIV-positive and, in Russia's view, have no value as human beings."

Social media recruitment

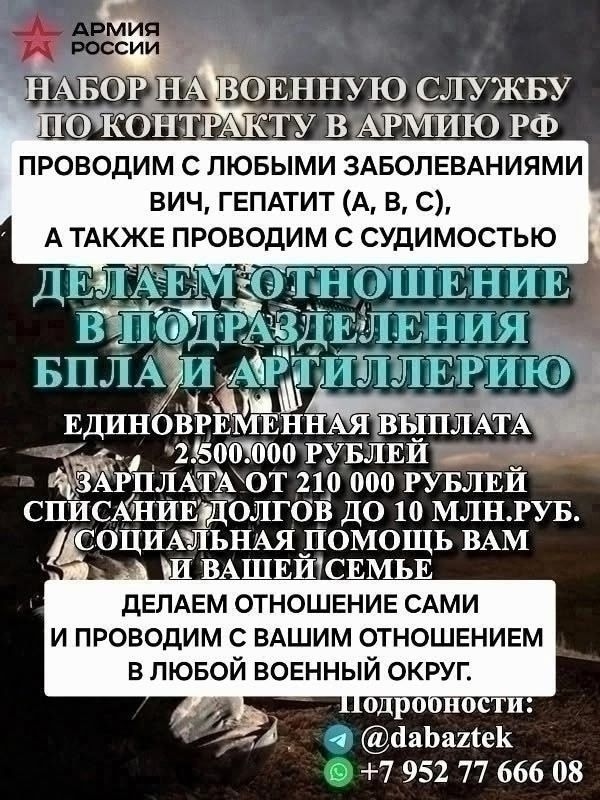

The Kyiv Independent reviewed several pro-war groups on the Russian VKontakte (VK) social network and found multiple posts encouraging people with HIV, hepatitis, and syphilis to join the army.

On VKontakte (VK), recruitment ads for the Russian army resemble job listings, dressed in bold fonts and propaganda-style imagery. They promise sign up bonuses of up to 3 million rubles ($38,000), debt relief, and even fast-track citizenship to attract foreigners as well.

Some posters go further, openly stating that people with serious illnesses, disabilities, or criminal records are welcome to apply.

Several posts mention that the army is ready to take in people with "Umbrella," which appears to be a code word for recruits with life-threatening illnesses. The name derives from a Wagner Group unit that recruited people with HIV, hepatitis, or syphilis.

For example, in a pro-war VKontakte (VK) group called "SVO Updates, Army, Russia," recruitment ads are posted daily. They usually include the contact details of a person potential recruits can message. Similar ads — sometimes with the same contacts — also appear in other groups with tens of thousands of followers.

It's unclear to what extent this method is effective and how many people are being recruited this way.

Russian-occupied territories

Russian troops are also mobilizing residents of Ukraine's occupied territories, where the healthcare system is dire, with diseases like HIV and hepatitis nearing an epidemic.

Vira Yastrebova, director of the Eastern Human Rights Group, citing her sources in Russian-occupied territories in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, said that people living with HIV and hepatitis are being sent to assault units. They receive little to no medical care.

"Due to the growing number of hepatitis C and HIV cases each year, there are more and more people infected, and they (Russia) are unable to deal with it," Yastrebova told the Kyiv Independent.

"They have no interest in treating people or creating conditions to halt the epidemic."

Access to medical treatment for HIV-positive individuals also depends on having a Russian passport, which Russia is forcibly imposing on residents of the occupied territories in line with Putin's decree.

According to Yastrebova, recruitment centers in the occupied territories display posters encouraging people with HIV and hepatitis to join the Russian army.

"'This is your last chance,'" Yastrebova said, referring to the slogans used in recruitment ads in the occupied territories.

To obtain medication, people living under occupation turn to private chat groups, hiding their HIV-positive status because of the stigma surrounding the disease in Russia.

Despite hurdles, Yakovets said that their organization manages to help some people in occupied territories. Still, the situation remains "very bad," and many people living with HIV are trying to flee Russian-occupied areas to seek treatment abroad, she said.

Ukrainian army

Unlike Russia, Ukraine has clear regulations for the service of people with HIV. Still, some problems remain.

HIV status alone is not grounds for exemption from mobilization or military service. Whether someone is fit to serve depends on other health issues, and each case is reviewed separately.

Ukraine typically assigns HIV-positive soldiers to non-combat or support roles where they can safely receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), Yakovets said.

But according to her, risks exist even before recruitment. Some medical commissions fail to detect diagnoses, and those mobilized into combat units struggle to access ART mainly due to supply chain disruptions.

Ukraine also does not keep a separate register of HIV-positive people serving in the military, Yakovets added.

"If someone is in a combat unit, the situation is critical," she told the Kyiv Independent.

"These soldiers must either interrupt their treatment, which threatens both their health and the health of their comrades, or rely on relatives sending medication through delivery services to the front line."

Note from the author:

Hello there! This is Kateryna Denisova, the author of this piece.

The Kyiv Independent doesn't have a wealthy owner or a paywall. Instead, we rely on readers like you to keep our journalism funded. If you liked this article, please consider joining our community today.

Thank you.