These Ukrainian artists, writers were killed by Russia’s war

"My worst fear is coming true: I'm inside a new Executed Renaissance. As in the 1930s, Ukrainian artists are killed, their manuscripts disappear, and their memory is erased," Ukrainian writer Viktoriia Amelina penned in the foreword to the published diary of another author, Volodymyr Vakulenko, murdered during the Russian occupation of Izium.

Amelina, who dug up Vakulenko's notes he had hidden from the Russians in his yard and initiated the diary's publication, was also killed by Russia’s war. She died on July 1 after being critically injured in a Russian missile strike on Kramatorsk.

Vakulenko and Amelina are among dozens of Ukrainian cultural figures killed by Russian aggression. There is no official record of such losses, but two lists compiled by PEN Ukraine suggest that the full-scale invasion has claimed the lives of at least 65 Ukrainian cultural figures.

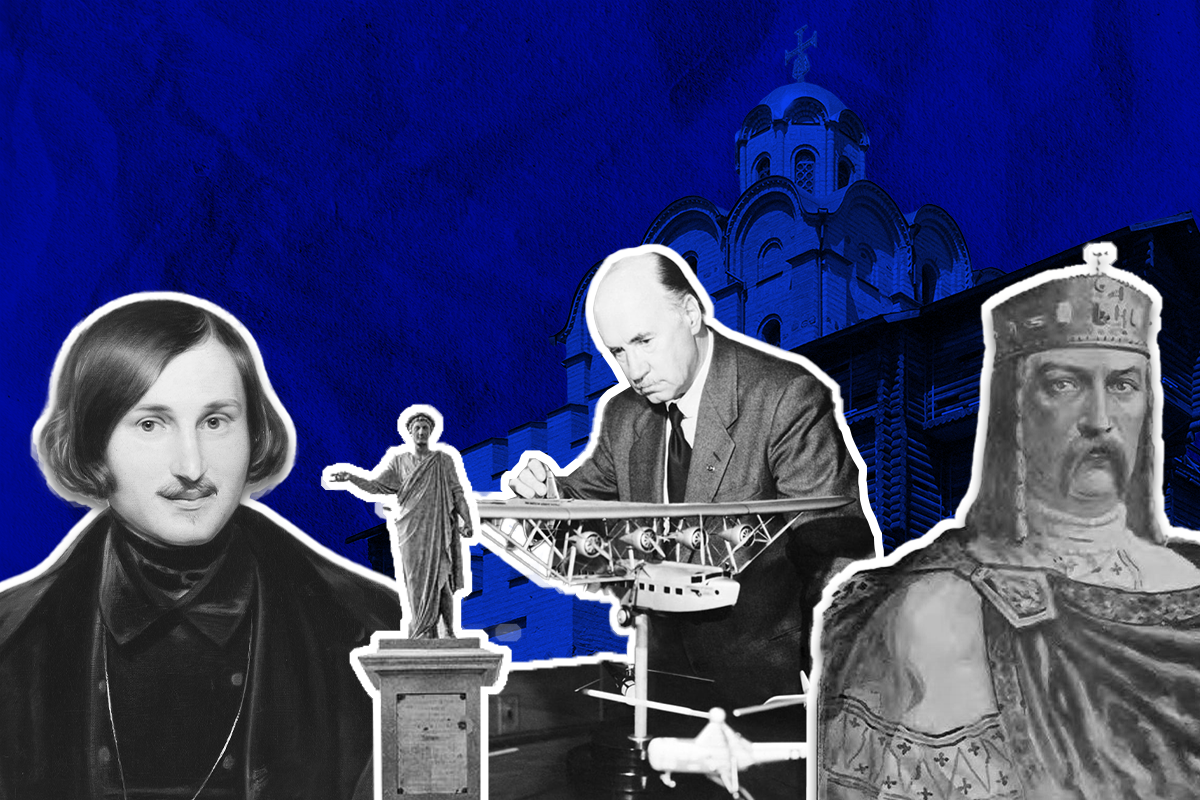

Some were killed as civilians in missile attacks or in occupation, others as service members after joining the Armed Forces to defend their country. But all of these deaths have contributed to what experts call Russia's hundreds-year campaign against Ukrainian culture.

"(Russian President Vladimir) Putin has said that Ukraine has no right to exist as a state, so they (Russians) are trying to erase all evidence of this existence," Olha Honchar, director of Lviv's Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes, told the Kyiv Independent.

"If you have a pro-Ukrainian position, engage in culture, language, literature, history — then you are a target for destruction on the occupiers’ lists."

The Kyiv Independent tells the stories of five cultural figures Ukraine has lost to Russia's war since Feb. 24, 2022.

Yurii Kerpatenko, conductor of the Kherson Oblast Philarmonic

Kherson locals knew Yurii Kerpatenko, a conductor at the Kherson Oblast Philarmonic, as a man of principle.

"If he didn't like something, he would voice it strongly," Kerpatenko's colleague Maksym Lozovyi told the Kyiv Independent.

He thinks that may have been the case when Russians asked Kerpatenko to hold a concert at the philharmonic to create the illusion of a "thriving" cultural scene under what was then a seven-month-long occupation.

According to local authorities, 46-year-old Kerpatenko repeatedly refused to cooperate with the invaders until one day, Russian servicemen shot him through the closed door of his apartment.

Many of their colleagues tried to avoid the same fate either by fleeing the occupation or complying with Russian orders, Lozovyi said. Kerpatenko not only stayed in occupied Kherson but also openly criticized the Russian leadership and Moscow's top proxy in the city.

"Musician for life," says Kerpatenko's Facebook page description. "When he listened to music, he just 'soared.' You could see from his movements how much he enjoyed it,” Lozovyi said.

Lozovyi called the loss of Kerpatenko, who he said was also known for his orchestrations abroad, irreplaceable for Kherson Oblast's cultural scene, expressing pessimism in the philharmonic's future.

"Everything ended with Yura's death. There is nobody like him, and there won’t be for the next few years or even decades."

Viktor Onysko, film editor

Ukrainian film editor Viktor Onysko always hated war, distinguished cultural manager and Onysko’s wife, Olha Birzul, told the Kyiv Independent. “It was not his element at all.”

But when Russia poured thousands of its troops into Ukraine, the 40-year-old Kyiv native joined the army, feeling it was unfair to wait for others to stop the invasion.

His high sense of justice pushed him to take part in the Orange Revolution and EuroMaidan Revolution, the most consequential uprisings in modern-day Ukraine. The same sense of justice brought him to the front line near the city of Soledar in Donetsk Oblast.

On Dec. 30, 2022, the film editor turned company commander with the call sign “Tarantino” was withdrawing his troops from the area when Russian forces spotted their positions, opening heavy fire and killing Onysko.

Over his 15-year-long career, Onysko contributed to over 20 Ukrainian movies and TV series, including “The Stronghold,” “The Rising Hawk,” and “Felix Austria.” His last film shoots took place in Kherson Oblast, where Onysko returned a year later to liberate the region from Russian occupation.

Having no previous military experience, he kept telling his wife it was their generation that must stop this war so that younger Ukrainians could go on with their lives.

When asked what Onysko’s career plans were, Birzul hesitated, saying that her husband had a hard time making plans in an unstable Ukrainian film industry.

Onysko used to say that “there is no cinema more interesting than life,” according to his wife.

“He just wanted to live in a free country, raise his (10-year-old) daughter, and be a decent person responsible for what he does, says, and how he lives.”

Liubov Panchenko, artist and fashion designer

Liubov Panchenko belonged to the Sixtiers, a Ukrainian dissident movement that revived the country’s culture during the Khrushchev Thaw. The influential yet not very well-known artist and fashion designer was surrounded by prominent intellectuals of her time, like Alla Horska and Viacheslav Chornovil, most of whom fell victim to Soviet repressions.

Regardless of what she was working on — costumes, illustrations, fabric collages, embroidered towels, or shirts — Panchenko always relied on Ukrainian tradition, using national ornaments and other authentic elements.

The Soviet authorities showcased her works to foreigners as “proof of the free development of national culture” but ensured her talent remained unknown to the general public, reads Panchenko’s biography published by the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory.

In 1992, a year after Ukraine regained its independence, she finally got her first open exhibition. But the most productive years were already behind her.

A native of Bucha, a suburb just west of Kyiv, Panchenko faced Russian occupation alone at the age of 84, deprived of social services available to her before the invasion. When a projectile landed in her yard, a neighbor came to help and found the woman “beyond exhausted" from a month of hunger, said the head of the Ukrainian Sixtiers Dissident Movement Museum Olena Lodzynska, who knew Panchenko personally.

After Ukraine liberated Bucha, Panchenko was hospitalized but died shortly thereafter. "What we saw at the hospital was a skeleton covered with skin," Lodzynska said.

Panchenko died in April 2022, survived by no children but a collection of dozens of artworks at the Sixtiers Museum in Kyiv.

Oleksandr Shapoval, ex-soloist of Ukraine’s National Opera and Ballet Theater

In 2021, after almost two decades at Ukraine's National Opera and Ballet Theater, award-winning ballet dancer Oleksandr Shapoval finished his career on stage and focused on teaching.

A year later, on the second day of Russia's full-scale invasion, Shapoval called his shocked wife from an enlistment office, saying he had joined the Territorial Defense Forces.

Brought up on World War II stories from his grandfather, the 47-year-old Kyiv native felt he could not stand aside, trading sophisticated choreography classes for the position of a grenade launcher in an assault squad.

"When he was sent (near) Donetsk, I couldn't walk for two days," Shapoval's wife, Tetiana, told the Kyiv Independent with her voice trembling.

She was told that a Russian projectile landed next to his feet while he was trying to evacuate the bodies of fallen brothers-in-arms.

In their last phone call, Shapoval told his 21-year-old son, "I just really want to sleep and to hug you all."

Before the full-scale war, Shapoval finally came to peace with his retirement, overcoming fears of leaving the theater that had become his second home. He was deeply invested in each of the 30 roles he had throughout his career, practicing them whenever he could, said Tetiana.

Whether it was Tybalt from "Romeo and Juliet" or Jose Escamillo from "Carmen Suite," Shapoval lived through all his roles, inspiring colleagues, the audience, and his daughter Mariia. She followed in her father's footsteps and is now studying in a U.K. ballet school.

Olha Pavlenko, artist and researcher of Ukrainian cuisine

Olha Pavlenko, 38, was the type of person you would call versatile. She taught art classes for children, often those with disabilities, in her studio called "Kolorovo" (Colorful), researched the history and traditions of her native region, Kirovohrad, organized cooking workshops, art exhibitions, and charity auctions.

But Pavlenko's most notable achievement was what she called "the red book of Ukrainian culinary art," preserving authentic recipes from across the country. She spent two years creating the book “Live Ukrainian Cuisine,” based on the findings from her expeditions, archive records, and folklore, the artist's mother, Raisa Pavlenko, told the Kyiv Independent.

"At the age of 12, she baked her first bread," Raisa said with tenderness, recalling her daughter's deep-rooted love for cooking. Always keen to talk with local elderly women, Olha was very passionate about passing on the culinary knowledge of previous generations.

At the start of the full-scale invasion, Olha and her daughter evacuated to the U.S., but in April, they returned home, to the village of Uspenka, for several months, during which she planned to work on the book's second edition.

On June 27, she went to pick up a new phone from the nearest shopping mall — Kremenchuk's Amstor — right before a Russian Kh-22 cruise missile hit the building.

"Nobody could imagine that the shopping center would turn into a crematorium," Raisa said, recalling the deadly strike. Olha's body was identified by DNA testing and a piece of green-dyed hair.

After her death, Raisa's only consolation is to ensure her daughter's work lives on. She and activist Oksana Levkova are raising money to print additional copies of “Live Ukrainian Cuisine” and plan to publish its second edition. All funds from selling the first 500 copies supported Olha's daughter, who is now studying in the U.S.

Note from the author:

Hi! This is Dinara Khalilova, thank you for reading this article. As you can imagine, it was emotionally difficult to dive into the stories of people who could have done so much more for the Ukrainian culture but were killed by Russia’s war. I believe it’s important to keep showing the price Ukrainians pay for resisting Russia’s imperial aggression. If you do, too, please consider supporting our reporting.