These people just escaped Russian-occupied Ukraine — but some say they need to go back

After escaping Russian-occupied Ukraine, some people are now facing the impossible choice: to return. (Karolina Gulshani / The Kyiv Independent)

Editor’s note: The names of those coming from Russian-occupied territories have been changed for security reasons.

On the Ukraine-Belarus border, the wind cuts to the bone. Olena, a retiree from the Russian-occupied part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, has just crossed the Volyn humanitarian corridor after nearly four years of living in fear.

Dressed in the thickest, warmest overcoat she owns, Olena is still shivering from the cold. Yet she still vividly recalls the summer heat and drought in her native city in Ukraine's south, where the lack of rain made it difficult to grow her favorite tomatoes and watermelons.

She talks about this year's harvest, her beautiful house, and the horrors of life at home, where she was afraid to even go outside: "If you only knew how we live. We are constantly afraid of everything," she says through tears.

"There are more and more Russians in my area. God forbid I say something wrong to my neighbors."

But despite the horrors Olena describes, she says she needs to go back after visiting her children.

"We just built the house... How can we now abandon it and give everything to the Russians?" she says.

The Volyn humanitarian corridor

Located in Ukraine’s northwestern Volyn Oblast, the Volyn humanitarian corridor, is the only working checkpoint between Ukraine and Belarus, and is almost exclusively used by people escaping the occupied territories.

The last direct route from Russia to Ukraine through a checkpoint in Sumy Oblast was closed in August 2024 amid escalating Russian attacks in the oblast.

Given the territory of Belarus was used by Russia to launch its full-scale invasion, the area around the crossing is heavily fortified with mines and anti-tank hedgehogs.

UNHCR Border Monitoring report found 45% of those using the corridor did not intend to stay in Ukraine — of those, 83% planned to return to Russian-occupied territory, and 17% planned to go abroad to the EU countries.

"Currently, the situation (at the border) is completely under control," Margaryta Vershynina, the spokesperson for the 6th border guard detachment, told the Kyiv Independent, but added the situation is constantly monitored as "we do not rule out the possibility of provocations" from Belarus.

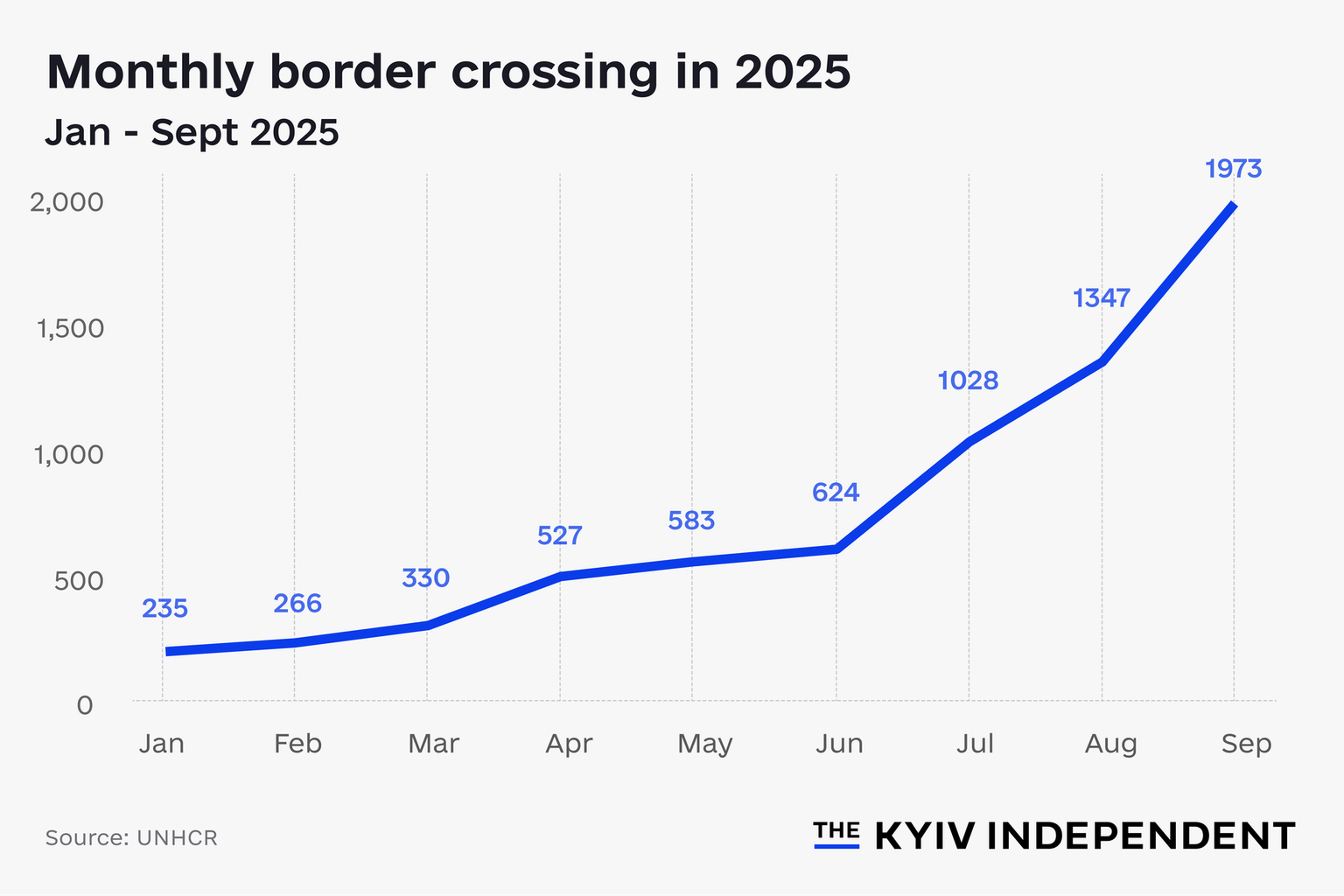

According to data provided by the Helping to Leave volunteering organization, which assists those who want to leave Russian occupation, the number of people using the corridor increased nine-fold since the beginning of 2025.

Life under Russian occupation

"People say they have no strength to stay there any longer. They are being pressured in every way," Liubov Palivoda, a Helping to Leave administrator at the border, told the Kyiv Independent.

Palivoda said that during the autumn, evacuees are leaving because of the upcoming hardships of winter, such as problems with water, electricity, and heating.

"Living under Russian occupation is suicide," 20-year-old Andrii from the occupied part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, says, describing how the intolerable living conditions are compounded by being constantly surrounded by the enemy.

"It's terrifying to be on the streets near Russian soldiers — I don't know what's going on in their heads, they might shoot or something."

The list of documented war crimes against Ukrainians in Russian-occupied territories is near-endless. Men are forcibly mobilized into Russia's army and forced to face the guns of their fellow countrymen. Sexual violence against women is used by Russian soldiers as a weapon of war. Children are either abducted, or forced into military camps and indoctrinated to fight against Ukraine in the future.

Torture is widespread, and as the Kremlin focuses on turning occupied Ukraine into a giant military base from which to launch attacks on the rest of the country, the neglect of the population's basic needs have lead to widespread drought.

Yet despite this, a UNHCR Border Monitoring report found 45% of those using the corridor did not intend to stay in Ukraine — of those, 83% planned to return to Russian-occupied territory, and 17% planned to go abroad to the EU countries.

Reasons to return

At the checkpoint, a middle-aged woman travelling from the Russian-occupied part of Luhansk Oblast smokes a cigarette near a Red Cross shack.

She came to visit her relatives in Ukraine, but needs to return in a few weeks' time to care for her mother who is too sick to leave.

"Living under occupation, they are all waiting for their homes to be liberated," Serhii, a Helping to Leave coordinator, told the Kyiv Independent, "so they will be able to work on their land, grow bread, plant watermelons, pumpkins, and do everything they used to do before the war."

Speaking of those who choose not to make the journey out, he adds: "It's difficult to live your whole life in one place, make something of it, and then go just somewhere else."

For those who decide to leave, an arduous journey still lies ahead.

The long journey

One elderly couple from Luhansk Oblast traveling for the first time since the start of the full-scale war to visit their children in Kharkiv had been on the road for three full days.

Before Russia's full-scale invasion, it took them only five hours.

Usually, people take private buses, or trains and volunteers help them buy tickets. Olena says she had also been travelling for three days, and had developed a severe pain in her leg.

Crossing through both Russian and Belarusian checkpoints is also an ordeal for Ukrainians. "I was scared that Russians would stop me somewhere, and find out that I am going to Ukraine," Andrii says.

A first attempt at the journey had been thwarted at the first checkpoint he encountered.

"You have three months to think it over and not go there," he was told by Russian border guards, but he tried again anyway. He could have made the journey far more simply by obtaining a Russian passport but this would also have meant registering for military service and the prospect of fighting against his own country.

"When we approached Ukraine and I saw our flag from afar, I realized that I was returning home," he says.

"I felt so calm because there was no threat from Ukrainian soldiers. Then I realized that everything would be fine and that there was nothing to be afraid of."

The relief of escape from Russian-occupied Ukraine — even if only temporary — is tangible at the checkpoint.

Olena smiles as she feeds four stray puppies. A woman from Luhansk Oblast beams as she calls her children to tell them she made it.

Serhii is loading people's belongings onto the vehicles in which they will continue their journey when he finds several large, heavy jars of preserved food — puzzled, he asks why someone has carried such heavy items for such a long way.

"Because they are homemade, made by my mother," a woman from the crowd replies.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Yuliia. Thank you for reading this article!

Typically, we invite you to join the Kyiv Independent community. However, this time, I kindly ask that you support the Helping to Leave organization, which helps to evacuate civilians from Russian-occupied areas.