Ships accused of stealing Ukrainian grain linked to Assad regime front

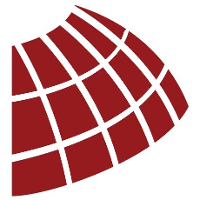

Three Syrian cargo vessels have been accused of trafficking in grain stolen from Russia-occupied Ukraine. Newly uncovered documents link the Seychelles company behind them to an apparent front for the regime of deposed dictator Bashar Al-Assad.

Three Syrian cargo ships have been accused of transporting grain stolen from Russian-occupied Ukraine. (James O’Brien/OCCRP/SIRAJ/Yörük Işık)

Editor's Note: This story was authored by Mohammad Bassiki (SIRAJ), Selma Mhaoud, and Shaya Laughlin, and published by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). The Kyiv Independent, a member center of OCCRP, is republishing it with permission.

Key findings:

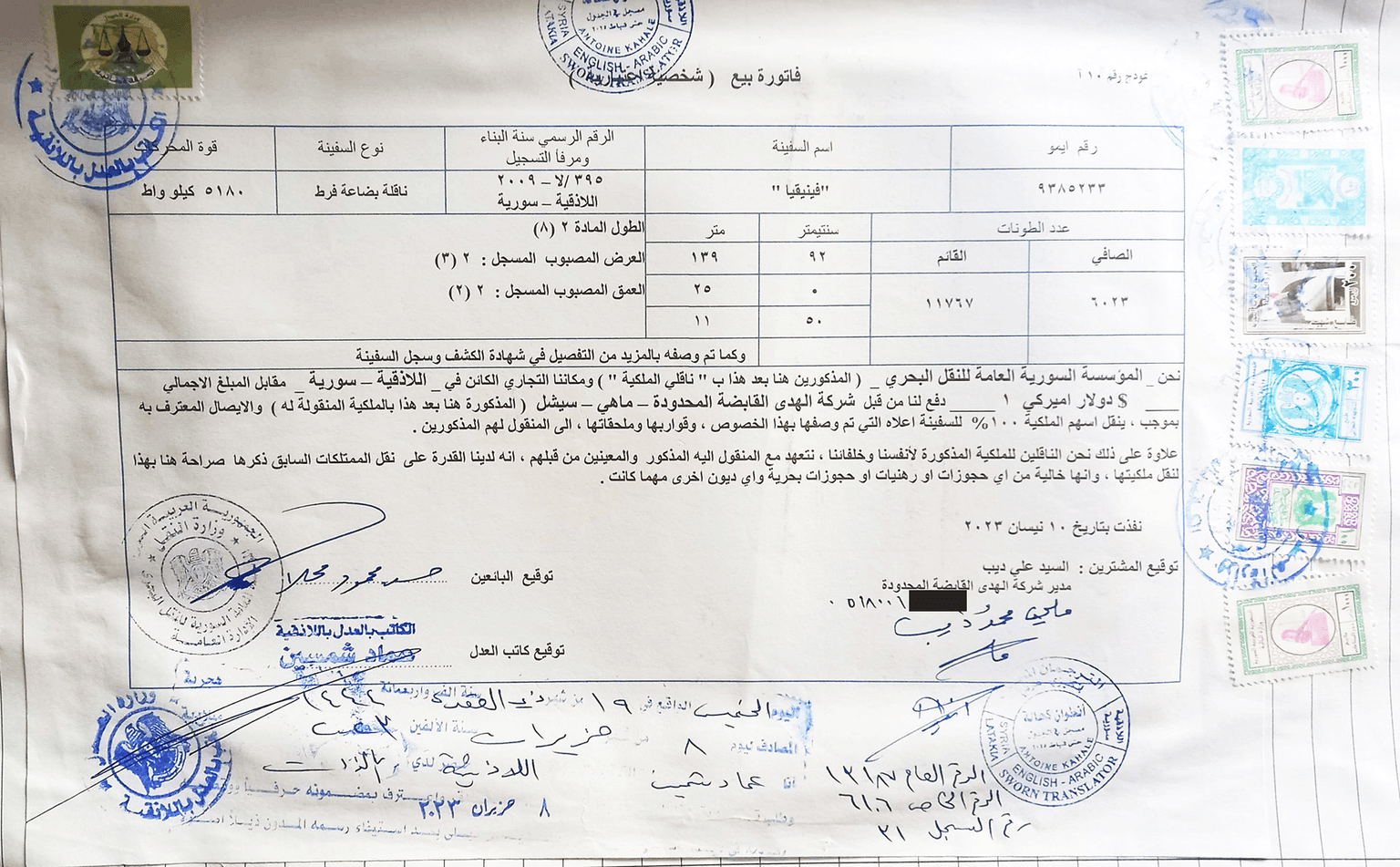

- Records reveal that the government of Bashar Al-Assad sold the three government-owned cargo ships to an opaque firm in the Seychelles in 2023 — two of them for just $1 each.

- Since then, the shadowy vessels have been sanctioned by the European Union for transporting grain stolen from Russia-occupied territory in Ukraine.

- While the owner of the Seychelles firm behind the ships is unknown, documents obtained by reporters show the company’s director has also held a large stake in a firm the EU calls a front for the Assad family.

- Records reveal the three ships have also been managed by companies with ties to Taher Kayali, a Syrian businessman sanctioned over alleged maritime trafficking of the drug Captagon.

On a clear, cool day in early January, the red deck of a cargo ship was spotted near a granary at a Black Sea port under the control of occupying Russian forces in Ukraine.

Alongside two sister ships, the bulk carrier had just been sanctioned by the European Union for belonging to Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet” — a network of vessels with murky ownership that have helped transport looted Ukrainian grain and other goods despite a web of international sanctions.

The three vessels, originally named the Finikia, the Laodicea, and the Souria, were once owned by the Syrian government, a key ally to Russia under the rule of former dictator Bashar Al-Assad.

But in 2023, they were quietly offloaded to an offshore firm in the Seychelles, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean that maintains strict corporate secrecy regulations and does not publicly reveal the names of company owners. This June, the ships were among hundreds of Syrian entities and individuals that the U.S. Treasury Department cleared from its sanctions list, granting relief to the country’s new government after Assad’s ouster.

But journalists can now reveal that the Seychelles company that bought and still owns two of the ships was directed by an apparent insider from the Assad regime, according to sales contracts and corporate records obtained by OCCRP and its Syrian partner SIRAJ.

There is another indication that the vessels may have been appropriated by those close to the former dictator before his fall: At least two of the ships were sold by a Syrian government agency to the Seychelles firm for $1 each.

“Selling multi-million dollar hulls for $1 strongly suggests a related-party deal designed to move assets off the Syrian state’s books while keeping them under the regime’s de facto control,” said Vittorio Maresca di Serracapriola, a sanctions specialist at the New Zealand-based consultancy Karam Shaar Advisory, which focuses on Syria’s political economy.

He said it appeared to be a “textbook example” of “the broader cannibalization of the Syrian state” that took place in the final years of Assad’s rule.

“Public assets were stripped from the treasury and funnelled into offshore shells tied to his networks, blurring any line between state property and the former regime’s wealth,” he said. “Even after Assad’s ouster, these asset transfers show how entrenched his patronage system remains.”

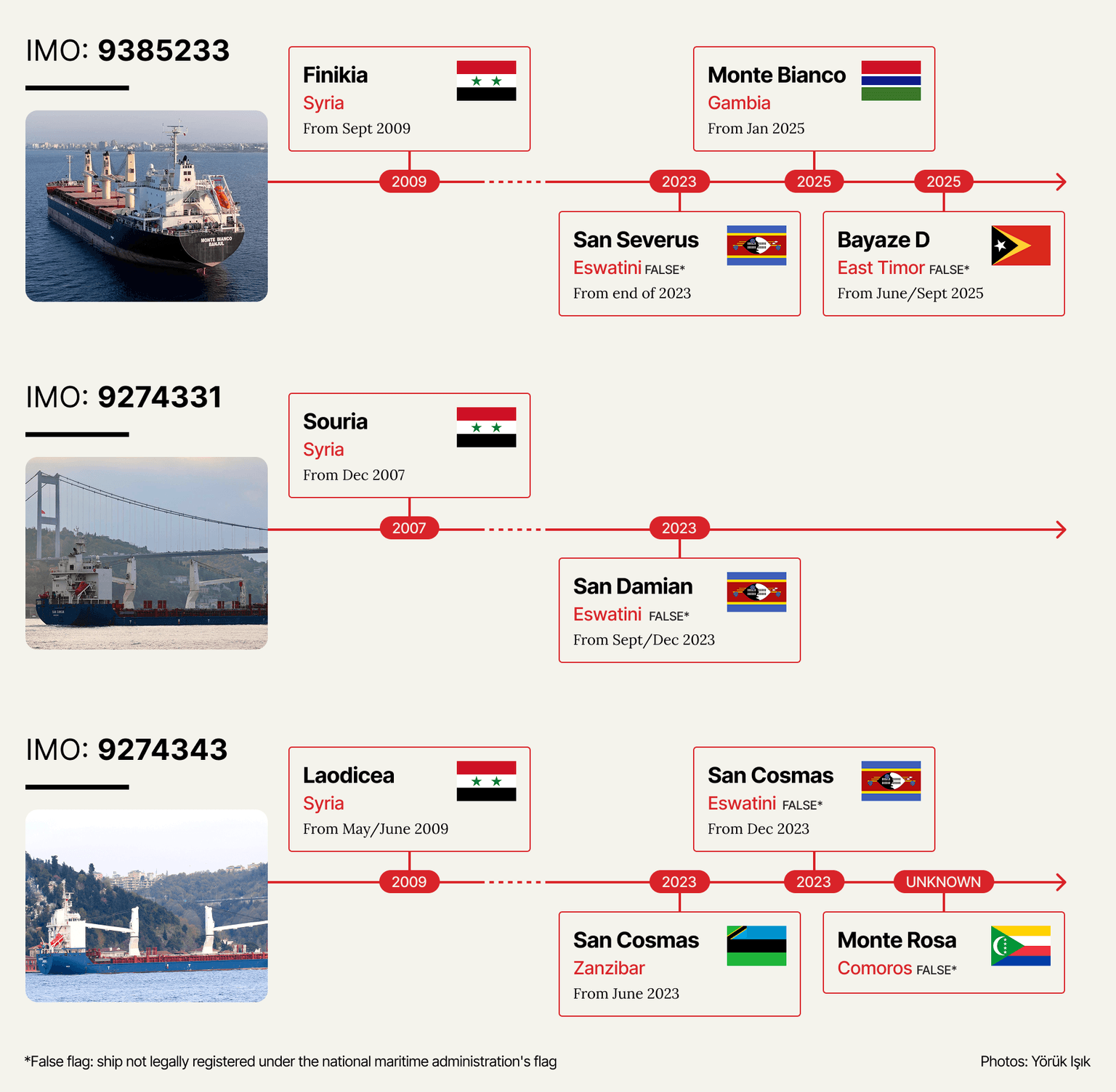

Since their 2023 sale, the three cargo freighters have navigated trade routes under a cloud of obfuscation, using multiple names, misrepresenting their country of registration with so-called “false flags,” and repeatedly switching off systems used to broadcast their location to authorities and other vessels.

Ukrainian authorities allege that all three of the ships belong to a fleet that has helped Russia expropriate some 15 million tons of Ukrainian grain since the 2022 invasion.

Reporters managed to piece together some of the ships’ recent movements with help from satellite images and ship tracking specialists. Crew lists and other documents obtained by reporters revealed another clue about who might be behind them: Since they were sold off by the government, the vessels have been managed — and in one case, acquired — by companies with ties to Taher Kayali, a 65-year-old Syrian under U.S., U.K., and EU sanctions for alleged maritime trafficking of Captagon, the illicit amphetamine drug whose lucrative trade was a financial lifeline for the Assad regime.

Kayali and the Seychelles company that bought the vessels in 2023, AlHouda Holding, did not respond to requests for comment. Reporters were unable to reach AlHouda Holding’s director at the time of the sale, a Syrian businessman named Ali Mohamed Deeb.

The ships’ sale aligns with a pattern documented in a 2024 report published by the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank. The report details how Assad brought key sectors of the Syrian economy under his control through the use of private business fronts, often led by low-profile proxies. This restructuring was aimed at insulating his regime from sanctions, and it further eroded “distinctions between the public budget and the Assad family’s personal finances,” the report notes.

In May 2025, a brief presidential decree signed by Syria’s new president Ahmed Al Sharaa established a commission tasked with tracing and investigating stolen funds until they can be “legally ascertained.” Aside from that, there has been little transparency on the new government’s efforts to recover the fortune that Assad, who has taken refuge in Russia, corruptly amassed during his rule and parked in luxury assets and secret bank accounts throughout the world.

The Syrian Ministry of Transport did not respond to requests for comment on the ships.

The Syrian General Authority for Land and Sea Ports, a new agency established by the country's transitional government, told OCCRP the sale of the ships took place before its creation in 2025 and did not provide any further information.

The one-dollar ships

For more than a decade, the Finikia, the Laodicea, and the Souria operated under the ownership of Syria’s General Authority for Maritime Transport, a division of the transport ministry under Assad’s government.

Made in China and Japan

The Syrian General Authority for Maritime Transport’s webpage shows that the Finikia, a bulk carrier with a capacity of 19,000 tons, was built in Japan in 2009 and bought by the Authority the same year. The Souria and the Laodicea were built in China in 2004 and 2005, respectively, each with a capacity of 13,000 tons.

In August 2015, the freighters were hit with U.S. sanctions that targeted resources used by the regime to wage violence against civilians in Syria’s civil war.

Then, in 2023, the three ships were sold to an obscure offshore company.

Incorporated in January 2019, the Seychelles-based AlHouda Holding has no functioning website, and until now, no information about the individuals directly involved in the firm has been disclosed to the public.

But the Syrian General Authority for Maritime Transport sold two of the ships — the Finikia and the Souria — to the company in April 2023 for the nominal price of just $1 apiece, according to sales contracts obtained by SIRAJ.

AlHouda acquired the third ship, the Laodicea, around the same time but OCCRP was unable to verify the sales price.

Yörük Işik, a maritime shipping analyst who runs the Istanbul-based Bosphorus Observer consultancy, said he had observed the ships multiple times in the Bosphorus Strait.

“Especially in the Bosphorus, you see so many Russian ships and their engines are so old, the vessel can hardly climb to the Black Sea… These three ships are not like that, they make good speed,” Işik said.

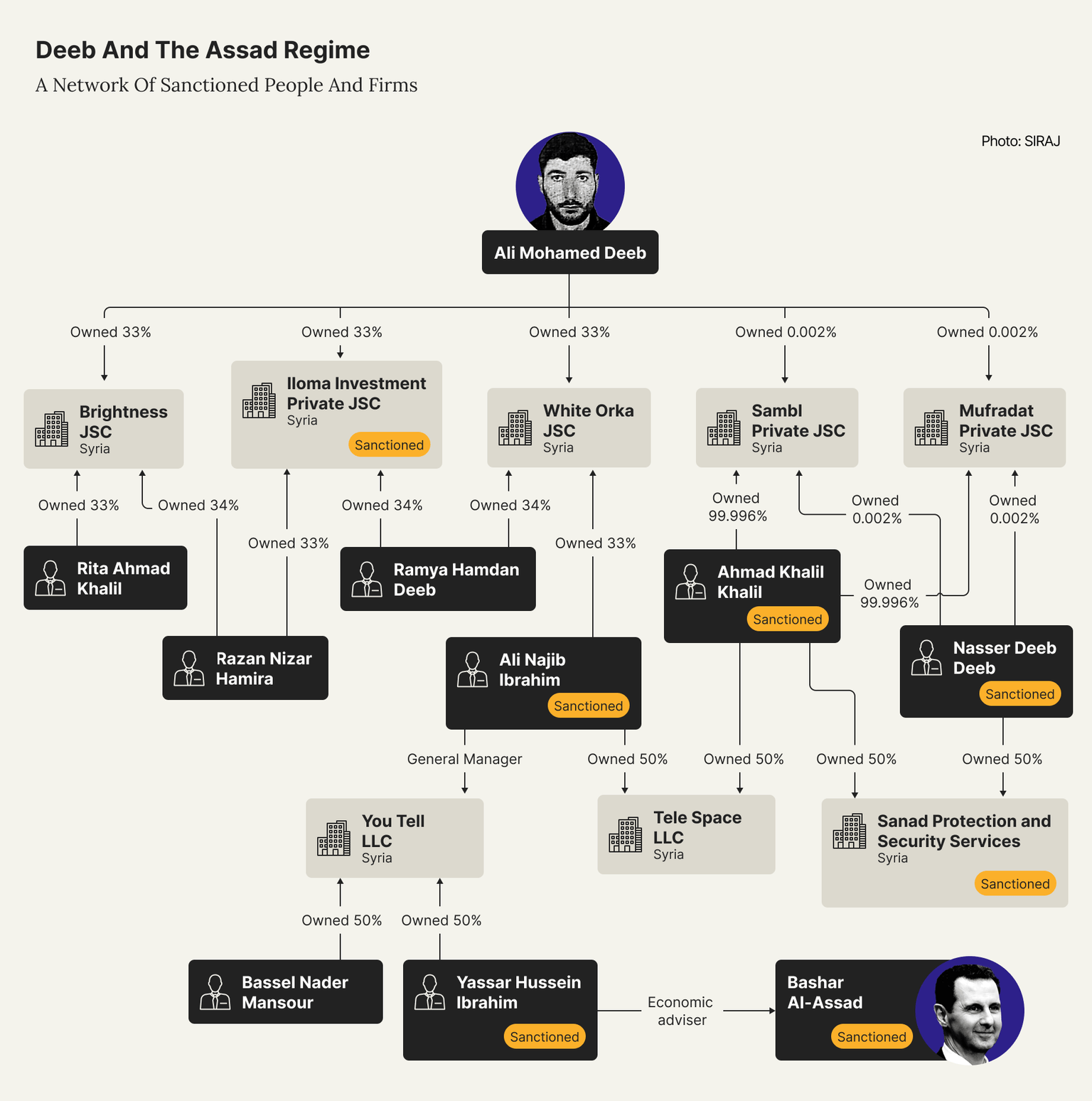

The AlHouda Holding director who signed his name to the $1 contracts, Ali Mohamed Deeb, has a minimal public profile. But Syrian corporate records and contracts obtained by OCCRP and SIRAJ reveal that he has deep ties to many individuals and companies connected to Assad’s regime, several of whom have been sanctioned for these links.

For instance, Deeb was a 33-percent shareholder in the Syrian company Iloma Investment Private JSC, which was founded in 2023 and the following year took over the operations and ticket revenue of the state-owned Syrian Airlines, according to documents leaked to SIRAJ.

The EU imposed sanctions on Iloma in January 2024, describing it as “a front for the Assad family and part of the regime’s efforts to personally gain from manipulation of the economy.”

Deeb also served as Iloma’s chairman in 2024, according to a contract between the company and Syrian Airlines.

The airline’s former general director Obeida Jibrail, who led the company during contract negotiations with Iloma, told SIRAJ that Deeb represented the interests of the Assad regime.

Iloma, which had no track record in the airline business, was “the company of the president,” Jibrail said he was told at the time.

Syrian corporate records show that Deeb also held stakes in at least eight other companies established from 2021-24. Three of his fellow shareholders in these firms were sanctioned by the EU for supporting and benefiting from the Assad regime.

They include:

- Ali Najib Ibrahim, a businessman active in telecommunications who the EU alleged owned “several shell companies that have been linked to the Syrian regime in attempts to circumvent sanctions.”

- Ahmad Khalil Khalil, co-owner of the company Sanad Protection and Security Services, which guarded Russian energy interests in Syria under the supervision of the Russian state-backed mercenary group Wagner, the EU alleged.

- Nasser Deeb Deeb, a co-owner of Sanad Protection and Security Services.

The first two businessmen, plus both of Ali Mohamed Deeb’s fellow shareholders in Iloma, were also identified in the Brookings report as part of a network of business fronts for Assad that included his former economic advisor, Yassar Hussein Ibrahim.

OCCRP was unable to reach Yassar Ibrahim, Iloma's shareholders, or Ali Najib Ibrahim for comment, while Ahmad Khalil Khalil and Nasser Deeb Deeb did not respond to queries sent by reporters.

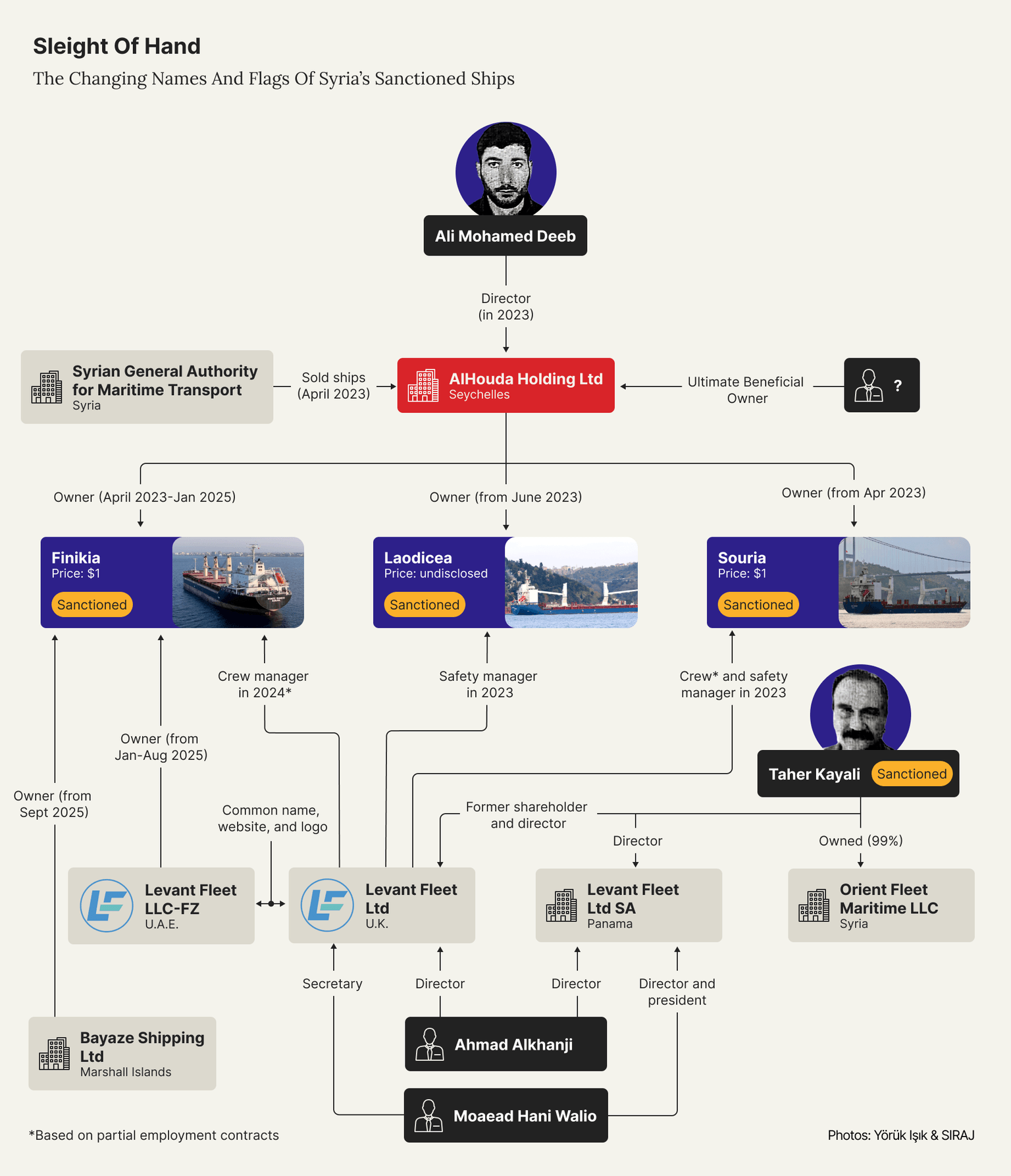

AlHouda continues to own Souria and Laodicea to this day, according to the International Maritime Organization, the United Nations agency responsible for safe shipping. But ownership of the third vessel — the Finikia — was transferred to another company in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

That company, records obtained by OCCRP and SIRAJ show, has multiple links to a sanctioned Syrian businessman notorious as an alleged Captagon trafficker.

The Captagon connection

On January 24 of this year, just over a month after it was hit with EU sanctions along with its sister ships over the alleged “transport of stolen Ukrainian grain,” ownership of the Finikia was registered to an UAE-incorporated company called Levant Fleet LLC-FZ, according to the shipping database Equasis.

Details about the shareholders and beneficiaries of Levant Fleet LLC-FZ are not publicly available. But reporters found two other companies in other jurisdictions also called Levant Fleet that are connected to Taher Kayali, a Syrian businessman whom the U.S., U.K., and EU have accused of trafficking the illicit amphetamine Captagon, raising questions about his possible involvement in Levant Fleet in the UAE. Levant Fleet Ltd. in the U.K. was previously owned by Kayali and appears to have provided management services to the Laodicea, the Souria, and the Finikia.

Archived versions of the UAE Levant Fleet’s website show that as recently as January of this year, the site presented itself as the public-facing portal of the British Levant Fleet Ltd, where Kayali was director between August 2020 and April 2023 and the company’s sole shareholder in 2020. He resigned a week after he was sanctioned by the British government, which alleged that he is a “business magnate with links to the captagon industry” who has been “tied to multiple captagon seizures, including in Europe.”

While Kayali is no longer involved in the U.K. company, records show he is a director of a Panamanian company also called Levant Fleet Ltd S.A. whose executives have the same names as those of Levant Fleet in London, suggesting the companies are related.

The U.K.-based Levant Fleet has served as the safety manager for the Laodicea and the Souria since 2023, according to the shipping database Equasis, and as a crew manager for the Souria and the Finikia in 2024, according to partial employment contracts obtained by SIRAJ.

And a crew list for the Souria dated January 5, 2024, features the name Orient Fleet at the top of the document. Kayali is a 99-percent shareholder of a Syrian company established in 2022 named Orient Fleet Maritime LLC.

The other shareholder of Kayali’s Orient Fleet Maritime bears the same name, Moaead Hani Walio, as the secretary of the U.K.-based Levant Fleet. Kayali and Walio have both served as officers in the U.K. and Panamanian Levant Fleets, while a third man, Ahmad AlKhanji, is also a director in both companies.

Walio did not respond to requests for comment. AlKhanji told OCCRP he parted ways with Levant Fleet, without specifying the jurisdiction, in 2023 due to “a dispute with the company personnel that continues to this day.”

Orient Fleet Maritime and the UAE- and U.K.-based Levant Fleet companies did not respond to requests for comment. But after sending the queries, OCCRP received a message from an unknown Syrian number, whose profile image featured the name — Neptunus — of another Syrian company belonging to Kayali that was hit with Western sanctions. The author said they were responding to questions about Levant Fleet and promised to provide “all necessary documents and materials” but did not do so in time for publication.

In September 2025, Finikia’s ownership changed again: It was transferred to Bayaze Shipping Ltd, a company incorporated in the Marshall Islands on 13 June, according to the International Maritime Organization and company records.

False flags

When Finikia was spotted this January by a granary at the Avlita cargo terminal in Sevastopol, the Ukrainian Black Sea port that Russia seized in February 2014, only two weeks had passed since it had been hit with EU sanctions.

The ship was now sailing under its third name since 2009 – Monte Bianco – and a new flag, Gambia, also its third since then. The AIS transponder used to broadcast its location had been switched off, but the vessel remained visible by satellite, according to an image provided to OCCRP by satellite intelligence company Vantor.

This type of regular rotation of names and flags of registration, plus the disabling of AIS transponders, has been a feature of all three of the Syrian vessels since they were sold by Assad’s regime in 2023. All three have also misrepresented their countries of registration with so-called “false flags.”

For instance, in December 2023, the freighters registered with the Kingdom of Eswatini, formerly known as Swaziland, in southern Africa. But just a month later, the landlocked nation rescinded the registrations, citing a “direct violation” of its policies, Eswatini maritime authorities told OCCRP.

All three of the Syrian freighters continued flying the Eswatini flag in 2024, primarily traveling between Russia and Syria, even though the African nation told the International Maritime Organization in a letter in August of last year that it had “not yet given permission to any company or agency to register ship vessels sailing in high seas in its flag.”

Michelle Bockmann, a senior maritime intelligence analyst with Windward, a maritime consultancy, said “flag-hopping” is typical behavior for sanctions-hit vessels that face limited options for countries willing to accept their registrations.

Lacking valid insurance and other safety certificates, such ships pose “significant threats” to maritime safety, security, and the environment, she wrote in a submission this year to the US Federal Maritime Commission. “These ships are essentially lawless and stateless.”

Asked about false-flagging, the International Maritime Organization said that it is a problematic practice that prevents authorities from exercising effective control over vessels at sea, but that “[t]here is currently no binding international framework to regulate the process of ship registration.”

Despite their efforts at obfuscation, satellite images and dedicated ship tracking publications helped reporters track some of the freighters’ recent movements.

For instance, the Souria, which is now called San Damian and still flies a false Eswatini flag, departed the Kavkaz port in southern Russia in November 2024 and anchored a little over a week later at the grain terminal in Egypt’s Alexandria port. Satellite imagery analyzed by OCCRP indicates the ship was moored in Syria’s Latakia port on June 30.

After its January stop in Sevastopol, the Finikia was seen sailing in the crystalline blue waters off Cyprus in June with an East Timor flag that the International Maritime Organization website describes as “false.” The East Timor ship registry told OCCRP in July that the jurisdiction does not maintain an international ship registry and it has no knowledge of the vessel.

Işık from the Bosphorus Observer consultancy spotted the ship — with yet another new name, Bayaze D — crossing the Bosphorus a few weeks later. According to the ship-tracking website VesselFinder it was heading for Russia’s Kavkaz port. Later that month, on July 17, it was again seen near Istanbul.

According to Vladyslav Vlasiuk, sanctions commissioner for Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, the Finikia made a call at the occupied port of Komysh-Burun as recently as August 2025. (Ship-tracking data reviewed by OCCRP shows the vessel in the area at the time.).

The Laodicea, meanwhile, was seen in the vicinity of Simferopol in Russian-occupied Crimea last June, and was spotted several months later sailing near Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey before making a stop in Lebanon. In November 2024, it switched off its AIS transponder until April 2025.

During this “dark” period, SIRAJ reporters spotted the vessel anchored in Syria’s Latakia port in mid-January, just over five weeks after the fall of Assad’s regime.

The ship’s new name was hidden behind a tarp that someone had hung on the back of the vessel. But the new moniker — Monte Rosa — remained visible on a lifeboat on deck. A gust of wind lifted the tarp just long enough for reporters to see “Rosa” painted on the hull.

Ahmed Haj Bakri (SIRAJ), Rana Sabbagh, and Daraj contributed reporting.