Saudi Arabia’s planned oil production hike may not break Russia’s petro-export-fueled economy, but escalations between Israel and Iran could be a gold rush for Moscow.

Since late 2022, the OPEC oil cartel, of which Russia is a member, has withheld oil production and exports to prevent a surplus in the market. But Russia and other members didn’t follow the restrictions which got under the skin of OPEC’s de facto leader, Saudi Arabia.

In response, Riyadh said it would hike oil production in December which could cause global prices to deflate and penalize non-cooperative OPEC members. While Russia will also be allowed to boost oil production, its capacity to do so is far more limited than Saudi Arabia’s.

Oil and natural gas exports are the backbone of Russia’s economy, accounting for around 35-40% of its budget revenues pre-full-scale invasion. The country’s energy sector, led by CEOs close to President Vladimir Putin, has kept Russia reliant on fossil fuels to line its pockets with quick profits instead of seeking economic diversification and growth.

Russia is already discounting its Ural crude by $12-15 against Brent oil, the global benchmark, to offset the risks associated with Russian trade. On top of Group of Seven (G7) sanctions that have blocked Russia’s access to the Western oil market, Moscow and its war efforts could suffer if superior Saudi crude floods the market.

“For Russia, this is doubly dangerous because it will firstly force them to drop the prices of their oil to compete in the market, and also find buyers who are willing to take their oil despite existing sanctions,” Vaibhav Raghunandan, EU-Russia Analyst at the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), a think tank, told the Kyiv Independent.

Currently, Russian Ural crude prices are hovering around $67 per barrel with production costs around $17-18 per barrel. If prices slide to $30 per barrel, Russia’s economy would take a major stumble and hamper its war effort in Ukraine, Raghunandan said.

For now, this scenario looks unlikely unless there is a global recession, David Fyfe, chief economist at Argus Media, a market analyst group, told the Kyiv Independent. OPEC producers plan to gradually introduce oil to the market at an additional 198,000 barrels per day each month, which is not enough to dramatically reduce prices and suddenly crash Russia’s economy, he said.

Even if crude prices drop to $50 per barrel, which Riyadh says is a possibility, Russia could sustain itself for six months or more, he added.

Fyfe doesn’t see enough international demand for the extra barrels. The second quarter of 2025 will be the real test for the market, and it could cause OPEC to U-turn on the decision and cut production again.

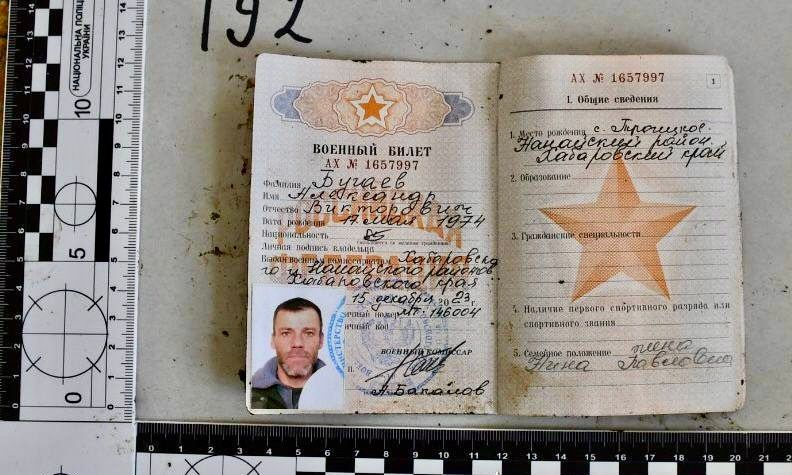

Russia’s oil sector has managed to bypass export sanctions to the West via its shadow fleet, although at incurred costs. Its oil and gas revenues this year jumped by around 50% compared to 2023.

However, Russia’s export options are limited. Moscow sends nearly half of its crude to China but the country is in the grips of an economic crisis fueled by the property market crash and Beijing’s oil demand has likely peaked, limiting Russia’s room for growth.

“It seems highly unlikely that Western Europe and the U.S. is going to be in the market for Russian oil or refined oil products anytime soon,” Fyfe said.

“If Russia wants to boost export revenues, it might sell a bit more (oil) to India. In a given year, it might sell a bit more to China, but there's not a huge import growth coming from China,” he added.

Moreover, the sanctions that limit Russia’s access to Western technology, which its oil assets rely on, could erode the industry over the next five years, he said. Moscow likely has one eye on the potential of tighter sanctions over the next few years, he added.

The saving grace for Russia’s oil sector would be an escalation in west Asia. Iran’s missile attacks on Israel on Oct. 1 caused oil prices to spike by nearly $10 a barrel as concerns arose over an Israeli retaliation.

Prices have been pulled back down again by a slightly anemic global economy, but if Israel targets Iran’s energy sector then they could jump again, noted Fyfe. Currently, Israel has said it will leave Iran’s oil and nuclear facilities alone following alarm bells from the Gulf States.

But if this situation does escalate, experts hypothesize that Iran could block the Strait of Hormuz, which sees 15-20% of global oil supplies pass through daily. The result would be a “bonanza for the Russian economy and its government” as prices skyrocket, said Vasily Astrov, an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, a think tank.

Yet Iran would be shooting itself in the foot by blocking its own oil exports. Tehran is only likely to resort to the option as a “last roll of the dice,” Fyfe said.