Trump wants Venezuela's oil — markets may not care

The El Palito refinery is seen at dusk in Puerto Cabello, Venezuela, on Dec. 18, 2025. (Jesus Vargas / Getty Images)

U.S. President Donald Trump made no secret of his plan for Venezuela.

"One of the things the United States gets out of this will be even lower energy prices," Trump said in a Jan. 9 meeting with energy executives.

“Our giant oil companies will be spending at least $100 billion of their money (in Venezuela),” the president said.

Darren Woods, head of oil giant Exxon Mobil, wasn’t sold on Trump’s idea.

“We’ve had our assets seized there twice, and so you can imagine that to reenter a third time would require some pretty significant changes,” he told the president.

With the country’s future unclear, U.S. involvement in Venezuela could theoretically send shock waves across global commodity markets, given that the country has the world’s largest confirmed oil reserves.

Exploiting them, however, is easier said than done, according to sector experts who spoke to the Kyiv Independent.

Sanctions, expensive production, and dilapidated infrastructures

A set of factors has made Venezuelan oil difficult to export, limiting the influence of the country’s energy on global markets. Since the late 2000s, the U.S. has attempted to make buying commodities from Venezuela impossible for third parties.

While output dwindled as a result of the measures, Venezuela was still able to sell smaller amounts of crude. As like Russia, it applied various schemes to avoid the U.S.-imposed embargoes.

“Venezuelan crude exports shipped by companies other than (U.S. oil giant) Chevron have largely been carried on ‘shadow fleet’ tankers, or tankers involved in illicit trades,” said Gus Vazquez, head of oil pricing in the Americas at Argus Media, a news outlet that specializes in commodity markets.

While these schemes helped the country sell its crude, they also came at a cost — Venezuelan oil traded at sizeable discounts in order to allow for sanctions circumvention.

The main client for this commodity was China, which imported approximately half of Venezuela's oil production, according to Argus Media estimates shared with the Kyiv Independent.

A more pressing issue with Venezuelan oil is the type of crude that the country produces.

Venezuela’s Merey blend is considered “heavy,” making its refinement more difficult and costly. In addition to high costs, Merey is sold at values of around $22 below that of Brent, largely due to the American embargo.

To make matters worse, years of sanctions, corruption, and mismanagement have brought Venezuela’s oil extraction industry to a dilapidated state. “To give an example of the scope of damage, sections of some unused gas pipelines have been stolen entirely, while many installations have been stripped of needed parts and have lacked needed maintenance for decades,” Vazquez explained.

As a result, over the years, Venezuela went from being one of the world’s largest oil producers to a minor player: while the country still produced about 3 million barrels per day in the early 2000s, this number stood at approximately 900,000 by the end of 2025.

Given the current state of Venezuela’s oil infrastructure, bringing production back to previous levels could take up to a decade, according to forecasts quoted by Reuters.

Venezuelan output could rise to approximately 1.3-1.4 million barrels per day within the next two years, but is unlikely to exceed this number. Over the next decade, this number could further rise to 2.5 million barrels per day, pending substantial investments in the country’s oil sector.

“The question is whether oil companies will invest the over $100 billion needed to develop Venezuela’s oil industry,” said Henry Sanderson, who focuses on clean energy at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a leading British think tank.

Oversupply in global markets

U.S. oil companies have been hesitant to invest in Venezuela, where the political regime remains in place, and the benefits of the business opportunities remain uncertain.

'No one wants to go in there when a random f*cking tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country,” one energy investor told the Financial Times.

However, even the slightest uptick in production can drop oil prices, as the world market is facing an oversupply, and demand is dropping.

“What’s interesting is that in the past days oil prices actually declined,” Sanderson explained. “This is interesting because in the past any (military) action like this would see prices rising. This shows that the world is awash in oil supplies, so there is actually not that much excitement about the U.S. developing more oil in Venezuela.”

In addition to this, more output is coming from sources such as Brazil and Guyana, which adds to rising fossil fuel production in the United States, under Donald Trump’s widely relayed suggestions to “drill, baby, drill.” The International Monetary Fund forecasted that 2026 would not be a year of mass global economic growth, a factor which further lowers demand for oil and drives down its prices.

“More structurally, we are starting to see demand being replaced to some extent by electric vehicles,” said Chris Aylett, a research fellow at the London-based think tank Chatham House, who focuses on energy.

“This has been most dramatic in China, which is the second-biggest oil consumer in the world. This energy revolution is clearly in the interests of China, which is a net importer of oil, and wants to reduce its consumption as much as it can.”

Given the global oversupply of oil, which was partly made possible by increased American production, experts who spoke to the Kyiv Independent were puzzled as to what the U.S. was attempting to achieve from control over Venezuela’s crude besides potentially driving prices to the ground.

One cited reason could be the type of refineries that are most common in the United States, which, for historical reasons, are designed to process the “heavy” kind of oil that Venezuela produces.

“The United States is the largest oil producer in the world, which would make you think that the country is energy secure, but there is a wrinkle in that, because most of the oil they produce is light oil from fracking, and the U.S. currently does not have sufficient infrastructure to refine this,” Aylett explained.

“So, actually, 60% of oil that goes into cars in the U.S. is ‘heavy’ oil from Canada that the U.S. can easily process. This makes sense economically, but it is possible that the Trump administration sees this dependency as a security issue.”

Influence on relations with China, Russia

As the economic incentives do not seem to be obvious, experts who spoke to the Kyiv Independent insisted on geopolitical benefits that the United States could be attempting to extract from control over Venezuela.

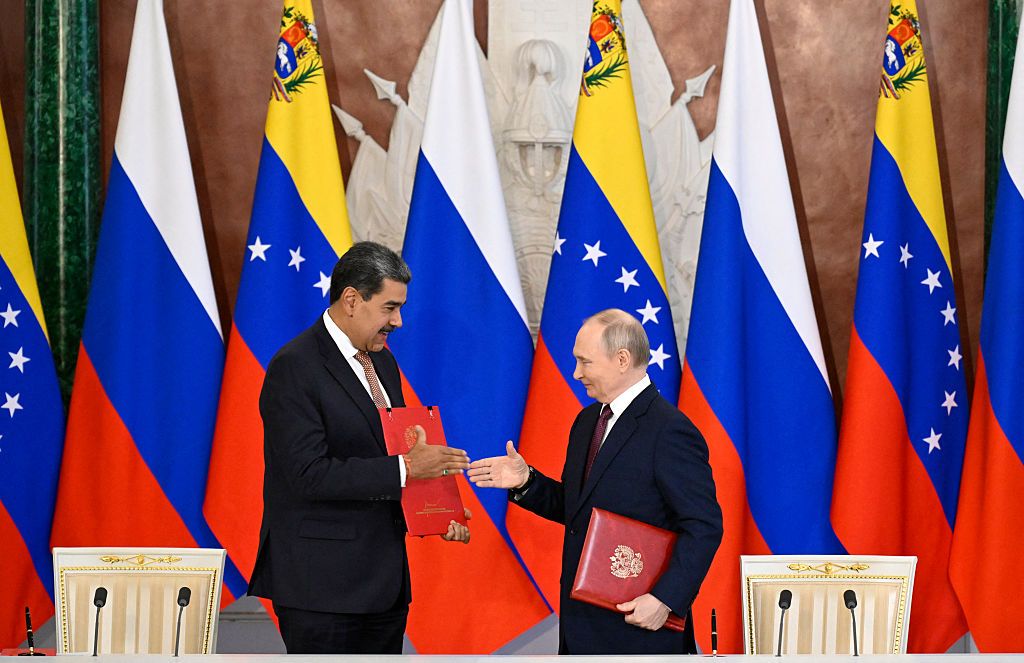

“The military operation was an immediate, televised success, and these are the kind of things that Trump likes,” Sanderson said. "In terms of strategy, Trump simply wants to show the world that the western hemisphere is the backyard of the United States, and that China and Russia have no place there.”

Aylett agreed that oil did not seem to be the “main motivation” of the U.S. intervention in Venezuela, despite being a “massively relevant” factor. “This looks more like making a play for a world of raw power and embracing this perspective of control over the Western Hemisphere,” the Chatham House expert said.

While the intervention in Venezuela could mean that the U.S. is interested in dividing the world into spheres of influence, this would not necessarily mean that the Trump administration considers Ukraine to be in Russia’s sphere.

“I don’t think it’s as simple as the U.S. takes Venezuela, so Russia can take Ukraine. Even if, of course, there is a fear that people around the world will start thinking this way, and will make their own conclusions,” Sanderson argued.

In general, U.S operations in Venezuela are not good news for Russia, either in terms of geopolitical influence or Russian profits from fossil fuel exports.

“Whether this ends up happening or not, the prospect of more Venezuelan crude coming on the global market could eventually bring oil prices down,” Aylett observed. “And, obviously, that would be bad for Russia and its ability to wage war.”

read also