As Iran erupts, Washington threatens, and Moscow watches in silence

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei addresses the nation in a state television broadcast in Tehran, Iran, on June 18, 2025. (Office of the Supreme Leader of Iran via Getty Images)

Over the past several years, Iran has witnessed a number of popular uprisings, varying in both scale and demands.

The ongoing mass protest movement that swept across the country in the closing days of 2025, however, is seen as the one that may actually topple the country’s autocratic regime.

The Jan. 8 demonstrations in Iran were the largest in years and more violent than many previous protests. A number of buildings were set ablaze, while protesters have been clear in their demands — "Death to (Ali) Khamenei" has been one of their chants.

Khamenei, Iran’s theocratic supreme leader, has pushed back. He said in a video address on Jan. 9 that he would suppress dissent, while the Internet has been shut down in the country.

Among those closely watching how — and for how long — Khamenei will cling to power are Russia and the U.S.

U.S. President Donald Trump has said that Iran would “get hit very hard” if the regime opens fire on protesters.

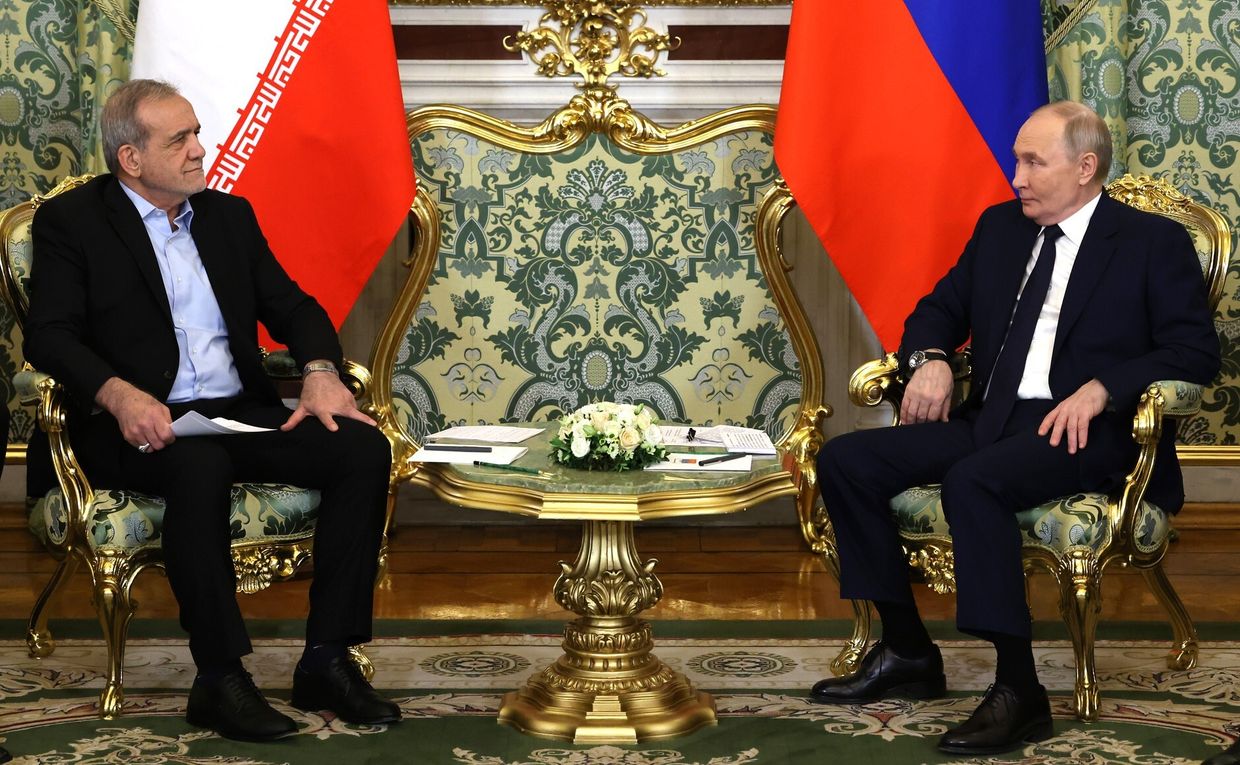

Russia, meanwhile, remains quiet. Moscow has been Tehran's primary arms supplier, while Iran has, in exchange, supplied Shahed combat drones to Russia.

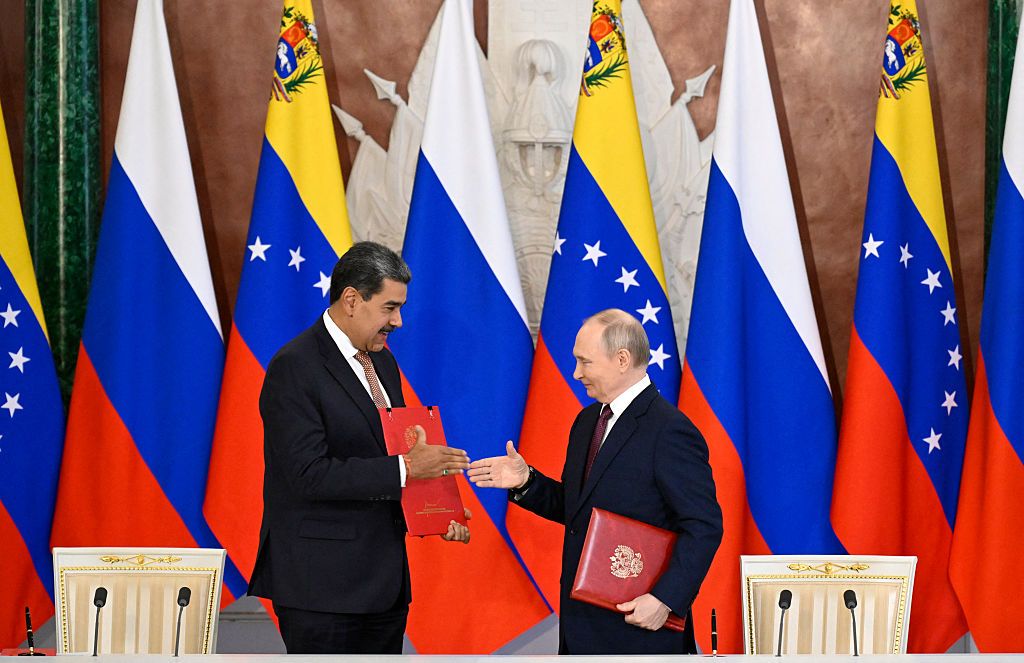

The two countries have deepened their alliance following Russia’s decision to launch an all-out war against Ukraine in 2022. The fall of Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro last week signaled, however, that there’s little Moscow can offer to save its allies.

“(Russian President Vladimir Putin) has already lost Syria, and now he’s losing Venezuela,” Olli Ruohomäki, a Middle East expert at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, told the Kyiv Independent.

It’s now up to the people of Iran to decide if Khamenei's unpopular regime will be next on that list.

Protests reach their culmination

The ongoing protests began on Dec. 28. The immediate reasons were high inflation and the severe depreciation of the Iranian rial. The demonstrations, however, quickly turned political, with the protesters demanding the ousting of Khamenei.

The broad geography of the demonstrations is unprecedented: protests have erupted in more than 100 cities and towns, with tens to hundreds of thousands taking to the streets. Protesters have clashed with security forces and burned a number of government buildings.

The protests reached their culmination on Jan. 8, when the turnout and scale rose significantly, prompting the regime to shut down the Internet.

The Jan. 8 demonstrations had an unusual spark — a call for action from Reza Pahlavi, the son of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the country’s monarch overthrown during the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Reza Pahlavi, a democrat and human rights defender, is seen as a unifying figure by many in Iran, with some demonstrators calling for the reinstatement of the Pahlavi dynasty.

The Iranian opposition estimated the Dec. 8 turnout at millions nationwide and claimed that the protests are the largest since 1979.

The Kyiv Independent could not independently verify these claims, and the Internet shutdown made it difficult to get credible information out of the country.

Serhiy Danylov, an expert at Ukraine’s Association of Middle East Studies, disputed the claims, saying that the 2009 protests against a rigged election were likely larger.

At least 62 protesters have been killed, hundreds have been injured, and more than 2,000 people have been arrested during the protests, according to the Iran Human Rights group.

Will the regime collapse?

Ruohomäki argued that the protests are "unprecedented in terms of the scale because previously there were protests only in the major towns and cities, but now they also take place in the rural areas."

"So I'm sensing that it's like the Arab Spring that started in Tunisia (in 2010). So there's a similar kind of mood in the air at the moment. And the protests are expanding."

Danylov told the Kyiv Independent that the current protests "are more dangerous" for the regime than previous ones because they are in favor of toppling the government rather than any cosmetic change that would allow the regime to survive.

"These protests could topple the regime, but the odds are still against the demonstrators."

He also argued that more social groups are involved in the protests, and demonstrators are more prepared to use violence to counter the use of force by the regime.

“I believe it’s over 50% probability,” Danylov said when talking about the outcome in which the regime collapses.

David Butter, a Middle East expert at Chatham House, said, however, that the Iranian regime has been weakened but "still has formidable repressive powers and strong internal security forces."

"The regime will probably try to weather the storm and offer some concessions," he added.

Alexander Palmer, an expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said that "these protests could topple the regime, but the odds are still against the demonstrators."

"Although the combination of economic, water, and security crises Iran now faces will make the regime more brittle, it has historically demonstrated extreme resilience in the face of demonstrations," he added.

"It will be the security forces' decisions that make the critical difference. We should all be watching for how they use force and whether regime violence creates a backlash or decreases the movement's momentum."

Foreign intervention?

On Jan. 8, Trump reiterated his threat that he would hit Iran "very hard" if protesters were killed, giving his country the option to intervene.

Danylov said that "the destruction (by the U.S. or Israel) of the headquarters of the security bloc involved in suppressing the protests could realistically trigger an effect sufficient to fragment government forces."

"(The Maduro scenario) is much more difficult to implement in Iran than in Venezuela because of the many logistical reasons," Ruohomäki said.

Jamie Shea, a defense and security analyst at Chatham House, argued that "a further intervention against Iranian military facilities might rally Iranians around the regime, which could then deflect attention away from the protests and towards the foreign threat."

Russia’s role

Another factor in the equation is the role of Russia, one of Iran's main allies.

In recent years, Russia's influence in the Middle East has declined as Israel dealt heavy blows to Iran's network of proxies. Specifically, Israel has killed Hamas and Hezbollah leaders, while Israeli and U.S. aircraft destroyed much of Iran's air defense and damaged nuclear enrichment facilities in the country in June 2025.

Russia's clout also diminished when the regime of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, who was backed by Moscow and Tehran, collapsed in 2024.

Butter argued that the potential fall of Khamenei's regime "could be negative for Russia — loss of a geopolitical ally, damage to arms procurement, and maybe knock-on effects on its economy, oil exports, if Iran increases its own oil exports with an easing of sanctions."

Ruohomäki said Russia is unlikely to help the Iranian regime suppress the protests, but could offer shelter, as it did to Assad.

"Russia did not save Assad," he added. "Russia did not save Maduro. Iran cannot count on Putin because their partnership is only transactional."