The Pereiaslav Agreement of January 18, 1654, was a pivotal treaty in Russo-Ukrainian history. (Daria Filipova)

In late April 2024, in central Kyiv, heavy cranes began dismantling a sculpture erected to commemorate 17th-century Pereiaslav Treaty between the Cossacks and Muscovites, symbolically closing a chapter of a shared history.

It was the very same agreement lauded by Russian President Vladimir Putin as supposed evidence of Ukraine's historical subservience to Moscow in a piece he penned months before launching the full-scale invasion.

What is the story behind the Pereiaslav Treaty, and why does it carry such a different meaning for both nations?

In January 1654, in the town of Pereiaslav in modern-day Ukraine, leaders of the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks pledged allegiance to Muscovite (Russian) Tsar Alexei I in exchange for his protection against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

While Soviet and Russian historiography has presented the event as the "reunification of the Rus" and proof of perpetual affinity between the Ukrainian and Russian peoples, Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy takes a wholly different view.

In his book on Ukraine’s history, “The Gates of Europe,” he writes that with the signing of the treaty, “The long and complex history of Russo-Ukrainian relations had begun.”

Pereiaslav's impact has rippled through centuries, representing a very different legacy for both nations.

For Russia, the treaty has played a crucial role in its imperial narratives about the Russo-Ukrainian "historical unity."

Plokhy retorts, however, that rather than a unification of one “Rus nation,” it was the beginning of the shared history of Ukrainians and the Russians, two separate peoples that have, since the fall of Kyivan Rus, evolved in a wholly different political and cultural milieu.

For Ukraine, it was the start of a painful story that ended in Ukraine's subjugation by Moscow. What began as a pragmatic alliance against Poland ended up in Russia completely dissolving the hetmanate a century later.

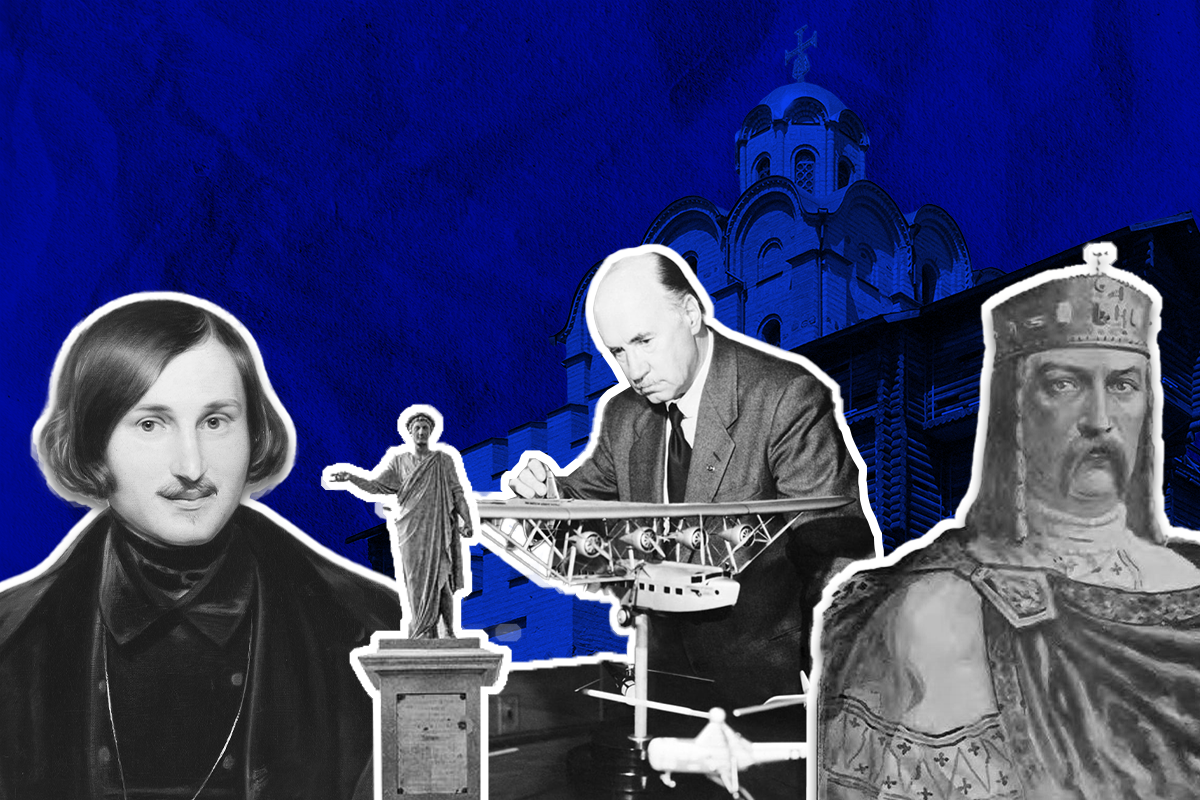

The Cossacks and the Muscovites

Looking more closely at the world in which the Pereiaslav Treaty, sometimes referred to as the Pereiaslav Council, was born, the narrative about the “reunification” of one people begins to waver.

While both can claim the legacy of the Kyivan Rus, the fate of what we today see as Russia and Ukraine diverged heavily after that medieval polity fell to the Mongol armies.

Muscovy’s early history flowed mostly separately from European events. In turn, much of today's Ukraine was incorporated into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, opening the door to various cultural influences from the continent.

This led to the development of different languages (famously, the two parties at the Pereiaslav Council needed translators), political values, religious thought, and even architecture, with the baroque style entering Ukraine much earlier than Russia.

The Polish rule over Ukraine was far from peaceful, however. The Cossacks, a mostly Orthodox people from the Ukrainian steppe with a strong militaristic and egalitarian tradition, led numerous revolts against their Catholic rules.

The largest one was launched by the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks under Hetman Khmelnytskyi in 1648. While initially scoring major victories and establishing himself as an effective ruler of much of today's Ukraine, the hetman was aware that he could not stand against Poland on his own for too long. He needed allies.

The Cossacks first joined forces with the Crimean Tatars, but the Crimean khan proved more interested in perpetual conflict and spoils of war rather than in a decisive victory of one side. Khmelnytskyi’s overtures to the khan’s masters, the Ottoman Empire, also did not bring the desired results, as the sultan was occupied elsewhere.

When the Cossack host turned to Moscow for aid, there were clear, pragmatic reasons. However, the shared Rus legacy and the common Orthodox faith may have made the tsar appear even more as a suitable candidate.

“We have convened a council open to the whole people so that you, together with us, might choose a sovereign for yourselves out of four… the first is the Turkish (sultan)... the second is the Crimean khan, the third is the Polish king who, if we wish, may still take us into his former favor, the fourth is the Orthodox sovereign of Great Rus, the tsar, Grand Prince Alexei Mikhailovich, the eastern sovereign of all Rus,” reads the transcription of Khmelnytskyi’s speech to Cossack officers.

The response was overwhelming support for the Orthodox tsar. Religious affinity may have indeed been an important factor in their decision. The wars of the 17th century were often fought along religious lines.

According to Plokhy, the actual decision was made before the hetman's theatrical exchange with his followers. The historian lists clear reasons why the other potential allies were unsuitable. The Crimean Tatars were unreliable, the Ottomans were too distant, and Poland had proven averse to granting the Cossacks the privileges they sought.

We can assume that Moscow was the most practical choice after eliminating all the other competitors. Plokhy also warned against overestimating the sense of shared religious or historical legacy among the Muscovites and Ukrainians.

"The tradition of Kyivan Rus' as represented by historical memory and religious belief still existed, but it was embodied only in a few handwritten chronicles," Plokhy writes.

"Four centuries of existence in different political conditions… had strengthened long-standing linguistic and cultural differences," he adds.

Furthermore, the suggestion in Putin's 2021 article "“On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” that the Cossacks saw themselves as "Russian" is even more doubtful. The 17th-century Muscovy claimed the legacy of old Rus but was a very different state from what we today understand as Russia. That was established by Peter I decades later.

The modern-day idea of a Russian nation came into existence even later in the 19th century.

The first probes into a possible alliance between the two states began already in 1648. Five years later, Moscow's parliamentary assembly, the Zemsky Sobor, sanctioned taking the hetmanate under the tsardom's patronage and launching a war against Poland-Lithuania despite the standing peace treaty.

A Muscovite delegation led by nobleman Vasiliy Buturin was dispatched to Pereiaslav, with the council itself taking place on Jan. 18, 1654. Dealings with the tsar's envoy revealed a cultural and political divide between the two parties. Buturin refused to discuss the terms of the agreement or to swear an oath to uphold the tsar's side of the treaty.

The hetman, accustomed to negotiating directly with Polish royal envoys, was taken aback, but the necessities of the situation made him accept the terms.

"Khmelnytskyi, who wanted Muscovite troops in battle as soon as possible, agreed to swear allegiance to the tsar with no reciprocal oath," Plokhy writes.

Nevertheless, Tsar Alexei stood by his words — at first.

Moscow recognized certain privileges to the Cossacks that the Polish king refused to grant, and its forces joined the fray against the Commonwealth armies.

The Cossacks and the Muscovites achieved success, with Khmelnytskyi's host besieging Lviv and the Muscovites entering Vilnius, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

As a matter of fact, this success was too great for the tsar, who feared that the Polish-Lithuanian state might actually fall apart and disrupt the balance in the region in favor of another power, Sweden.

In 1656, Moscow violated their agreement with the Cossacks and signed a separate peace deal with Poland, enraging Khmelnytskyi. Feeling betrayed by the tsar, the old hetman was ready to switch to another ally. But as he was planning overtures to the Swedish king, Khmelnytskyi died in August 1657, leaving his plans unfinished.

The tsar's decision and the hetman's outrage originated from their very different understanding of the treaty. Moscow's ruler believed he was simply gaining another obedient subject to whom, as an autocrat, he was bound by no obligations. Khmelnytskyi, while acknowledging the tsar as his superior, expected a reciprocal relationship.

For the tsars, the Pereiaslav Treaty meant that Ukraine had become their patrimony even after Khmelnytskyi's death. The rest of the 17th century saw the Cossacks divided and fighting among themselves, with Moscow aptly using the conflict to eventually gain control over the entire hetmanate.

With much of modern-day Ukraine safely within their grasp, the Muscovites would gradually take away the Cossacks' rights and privileges, crush any revolt that tried to halt the process, and eventually dissolve the Cossack Hetmanate completely in 1764.

The Pereiaslav Council, seen by Khmelnytskyi as a means to protect his fledgling state against Poland, has become a tool for Moscow to take over and destroy it completely.

The result of the Council started the red line that would permeate the rest of Russo-Ukrainian history.

Pereiaslav in Russian imperial narratives

“When I was asked about Russian-Ukrainian relations, I said that Russians and Ukrainians were one people — a single whole,” Putin wrote in his aforementioned 2021 article.

“Bohdan Khmelnytsky then made appeals to Moscow… (for aid). In January 1654, the Pereiaslav Council confirmed that decision. Subsequently, the ambassadors of Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Moscow visited dozens of cities, including (Kyiv), whose populations swore allegiance to the Russian tsar,” Putin wrote.

“In a letter to Moscow in 1654, Bohdan Khmelnytsky thanked Tsar Alexei Mikhaylovich for taking ‘the whole Zaporizhian Host and the whole Russian Orthodox world under the strong and high hand of the Tsar.’ It means that… the Cossacks referred to and defined themselves as Russian Orthodox people.”

This argument was meant to serve as one of the justifications for Russia’s subsequent full-scale invasion that has murdered thousands of Ukrainians. Putin argues that he is returning Ukraine to its historical, rightful place.

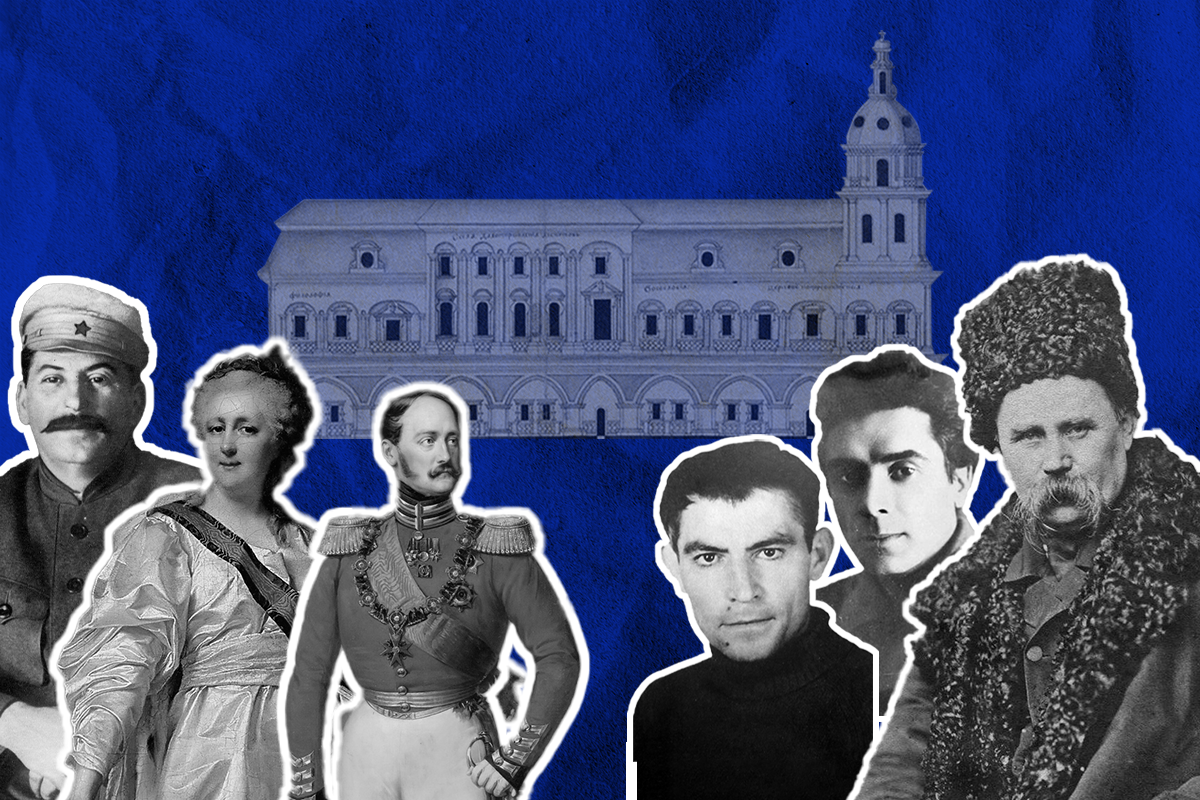

Let’s not give him too much credit, though, as he did not come up with the idea himself. Instead, he borrows heavily from Soviet historiography, which, in turn, was inspired by 19th-century imperial narratives.

Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, the same man who unleashed the Holodomor famine against the Ukrainian people, realized the benefits of reviving the memory of the shared Russo-Ukrainian history once Nazi Germany invaded the USSR.

The town of Pereiaslav was renamed "Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi" to honor the hetman seen by the Soviet authorities and their court historians as “Ukraine’s unifier with Russia.”

As Canadian-Ukrainian historian Serhy Yekelchyk writes, the Pereiaslav Council was cast as Ukraine’s “unbreakable union with the fraternal Russian people.”

A rather modest celebration of the treaty’s 290th anniversary in 1944 “reinstalled… the renewed cult of Pereiaslav (that) symbolized the dominant presence of the Russian elder brother,” Yekelchyk says in his book titled “Stalin's Empire of Memory.”

This was followed by a much grander celebration of the “Union of Russia and Ukraine Tercentenary” in 1954, already in the era of Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev.

The all-union event was accompanied by the publishing of a body of documents called the “Reunification of Ukraine with Russia” that were meant to testify to the “eternal union” between the two peoples… with Russia in the superior position, of course.

In 1982, the Soviet authorities opened a monument complex called Peoples' Friendship Arch in central Kyiv to celebrate the Russo-Ukrainian unity. It was dedicated to several historical events, including the 1,500th anniversary of the city's founding, the 60th anniversary of the USSR, and the Pereiaslav Council.

A part of the complex was a granite stele depicting participants of the council, dressed in historical Russian and Cossack garbs.

The statue remained there after Ukraine gained its independence in 1991 and even after the post-EuroMaidan government launched a large-scale decommunization and de-Sovietization process in 2015.

It was only after the outbreak of the full-scale war in 2022 that the arch complex began to be taken apart. The first part of the composition — a bronze statue of a Russian and Ukrainian worker — was removed in 2022.

In April 2024, the Culture Ministry abolished the landmark's status as a historic site.

Finally, on April 30, the dismantling of the Council statue itself finalized the divorce from the Kremlin-established Pereiaslav narrative.