Is 'Russians at War' propaganda? We asked 7 people in film who saw it

The filmmakers behind “Russians at War” have argued that a lot of the negative press surrounding the documentary comes from people who haven’t seen it. We asked the opinion of people in the film industry who have.

Director Anastasia Trofimova attends the photocall of the movie 'Russians at War' presented out of competition during the 81st International Venice Film Festival at Venice Lido, on Sep. 5, 2024. (Alberto Pizzoli / AFP via Getty Images)

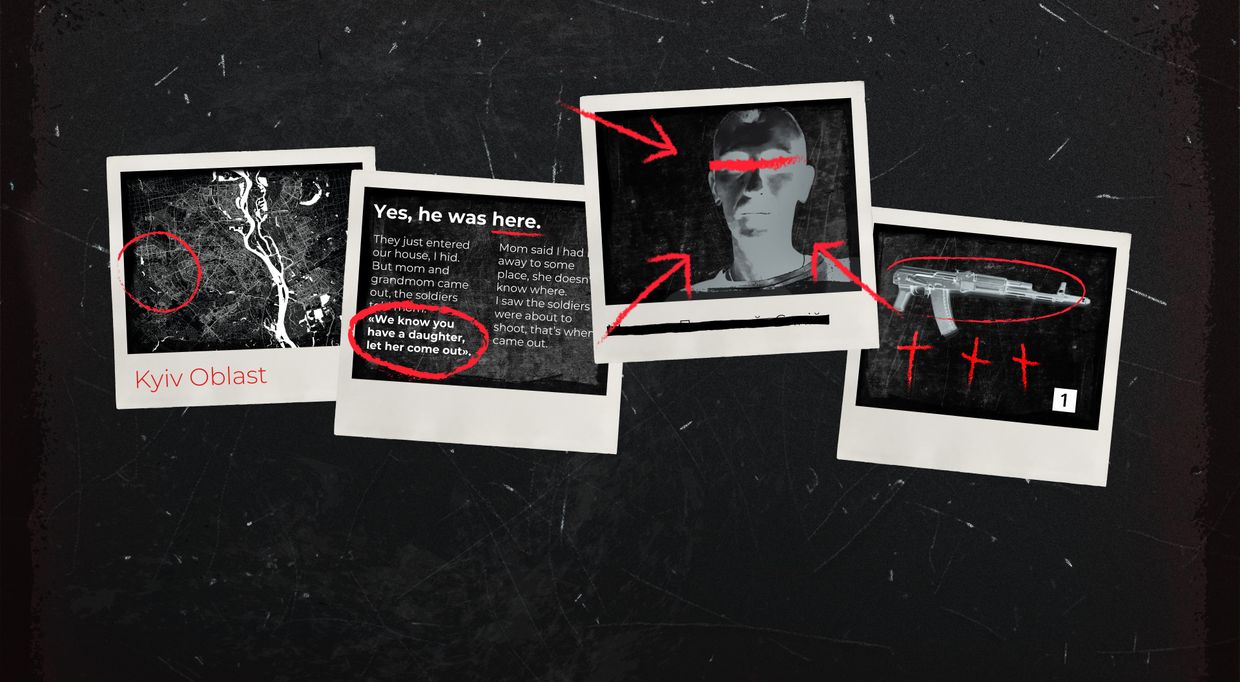

The documentary “Russians at War” has sparked controversy since its debut on the festival circuit, with many accusing it of whitewashing Russian soldiers and their crimes in Ukraine.

Canadian-Russian director Anastasia Trofimova has defended the film, calling it “anti-war.”

After facing backlash, the Toronto International Film Festival pulled screenings of the film, with both the festival and filmmakers citing concerns over potential violence. Toronto police said they were not aware of any serious threats, according to Canadian media reports.

The filmmakers behind “Russians at War” have argued that a lot of the negative press surrounding the documentary comes from people who haven’t seen it.

The Kyiv Independent requested a press copy of the film for review, but we were not provided with one, so we asked the opinion of seven people in the film industry who attended screenings of “Russians at War.”

Some testimonies have been shortened and edited for clarity.

Tetiana Mala, Ukrainian, communications manager

“Do you believe the Russian army commits war crimes?” Anastasia Trofimova asks one of her protagonists. He confidently responds, "No." Throughout the film, I kept hoping that somewhere before the credits rolled, we would see a slide showing crime statistics and explaining the truth about this war. But the director chooses an approach in which she doesn’t question a single fact or word in her film. Even though she actively uses voiceover, she could have used it to explain to the audience that everything they see and hear is disinformation and a repetition of Kremlin propaganda. Instead, she repeats it herself. By putting on the Russian military uniform, which she claims was given to her "to save her life," Anastasia broke all journalistic rules of objectivity and took a side. Spoiler: it's not the side of truth.

Throughout the film, I couldn't shake the feeling that every person on the screen was there for a reason. She speaks with an elderly civilian woman who confidently states that she fears the arrival of the Ukrainian army because they will kill her for speaking Russian. The main character of the film is a Ukrainian who claims that a “civil war” began in 2014, and the Ukrainian army started bombing its own cities, which is why he fled to Russia with his family. You will see many destroyed cities, but thanks to the director, you will never once doubt that this is all Ukraine's fault.

And if all of this could have just been a documentation of her surrounding reality, there is another aspect that makes it clear that the director is manipulating the viewer's perception and whitewashing Russian criminals. You will hear a lot of emotional music, see many tears over fallen comrades, and even a marriage proposal. Trofimova goes to great lengths to assure us that they are “just like us,” and we should sympathize with them, even though most of them joined the army voluntarily, which they acknowledge in the film.

Hugo Emmerzael, Dutch, film critic

At my most generous I’d describe “Russians At War” as a subpar documentary, which has trouble hiding its amateurish approach to the urgent subject matter. You might be even more generous and say that Anastasia Trofimova’s project comes from a place of sincere curiosity, which is often not a bad thing when it comes to non-fiction filmmaking. Her voiceovers structuring the material have the kind of wide-eyed naivety that has the potential to open up an interesting space for personal connections, as a kind of exercise in empathic filmmaking. This is already illustrated in the opening sequences of the film, in which Trofimova’s voiceover explains that without a press accreditation or permission from the Russian Defense Ministry, she’s wholly underprepared to undertake this journey — something that foreshadows my essential gripes with this film.

Ultimately, it’s hard to be generous to a film that doesn’t feel empathy at all to the matters being covered. Because in its conception, “Russians at War” is incredibly ill-advised. By being so consciously murky in its actual intent, and obscuring the most critical aspect of the narrative — the Ukrainian perspective on the war — all the possible ways you could forgive this film evaporate. As a result, the way Trofimova inserts herself in the film feels manipulative at best, and evil at worst. By blurring the boundaries between the capturing of reality at the front and constructing a narrative at this very same site of conflict, the film becomes an extension of the war apparatus it pretends to examine. As such, it’s an extremely upsetting and dangerous film, especially when it’s presented in the context of film festivals as a way to engage with “the other side” of the story of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Volodymyr Chernyshev, Ukrainian, film critic

The primary problem and danger of “Russians at War” lies in the fact that director Anastasia Trofimova essentially substitutes dialectics for rhetoric. At the beginning of the film, against a backdrop of solemnly dramatic music, Anastasia proclaims in a voiceover, “I'm going to the military front to understand what is happening.” However, instead of "discovering the truth," we witness a lousy attempt to justify and humanize the aggressors over the course of the next two hours, in which the hazardously inconsistent sophistry of drunken Russian soldiers is presented as an attribute of the “mysterious and eternally hapless Russian soul.”

By depicting the private lives of the occupiers — their families, front-line love stories, and “heartfelt” singalongs to (Russian singer) Andrey Gubin’s songs — the director tries to familiarize the audience with her characters and evoke sympathy for them. Moreover, Anastasia endeavors to empathize with Russians not only diegetically but also cinematically. For instance, throughout the film, images of the characters are interspersed with observational footage of kittens in the military camp's interiors. By the film's narrative conclusion, one of the "protagonists" declares: "They are sending us out, like blind kittens.”

Anna Hints, Estonian, film director

There's nothing inherently wrong with portraying a different side to the story, but as a filmmaker, it's essential to put things into context.

Trofimova uses narration as a cinematic tool and by analyzing it we get a very clear directorial standpoint. While stepping onto the soil of the land where she is going to film, we hear her say that this is either eastern Ukraine, part of the new Russian territories, or the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic, depending on the point of view. With this kind of narrative, she establishes her stance: for the director, there is a “fog of war” and ambiguity, where she avoids clearly stating that this is Ukrainian territory occupied by Russia since 2014. Trofimova's film also conveniently avoids any anti-Putin statements.

Peace and empathy are very important, but when they are preached together with violating the right for existence for a free Ukraine, it becomes highly problematic. The film shows the pointlessness of war without acknowledging the truth of the Russian invasion and the Russian military’s war crimes. So it’s just empathy for the soldiers without any critical context.

Darya Bassel, Ukrainian, film producer

“Russians at War” may mislead you into believing that it is an anti-war film, one that questions the current regime in Russia. However, what I witnessed is a prime example of pure Russian propaganda.

The filmmaker begins by expressing her surprise at the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. She does not mention that Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea in 2014 – these two events seem to not exist. The filmmaker also states that her country hasn’t participated in wars for many years and that she has only read about wars in books. It's interesting how the filmmaker seems to overlook her country's deep involvement in numerous wars and occupation over the past 30 years, including the Transnistrian War (1992-93), the Abkhazian War, both Chechen Wars (1994-96 and 1999-2009), the 2008 war in Georgia, and the 2015-2022 war in Syria.

Throughout the film, all characters express their confusion about their actions in Ukraine, stating they want the war to end and that most of them are fighting for money. In the final part of the film, the battalion is moved to Bakhmut, and most of the characters die in battle. We then see their brothers-in-arms and relatives grieving at their graves. All of them repeat that they don’t understand why this war is happening and who needs it. In the end, the filmmaker concludes that these are poor, ordinary Russian people who are being manipulated into war by larger political games. I found this perspective amusing because the filmmaker — like Putin and his regime — plays an interesting game with these people. They deny them the simple ability to possess dignity and to think and decide for themselves. To her, these people are merely powerless objects. If those engaged in a war that has lasted over 10 years were not powerless, it would imply that they, in the majority, actually support this war, wouldn’t it?

You will feel pity for the people depicted as dying in the film and for those we see crying for their loved ones. And you should — if you are a normal human being, you should feel pity, sadness, and emotion. However, it is also important to remember that these individuals joined the army that invaded an independent country, many of them willingly, as we learn from the film.

Anna Malgina, Russian, film critic

According to Trofimova, her film is anti-war, but it is unclear what the author has in mind – the war is presented in the film as a kind of natural disaster. It is unclear from the film who started this war, and where the soldiers are shooting. Considering that the director did not see any war crimes (according to her statement at the press conference), the soldiers are apparently shooting into the stratosphere, and the main occupation of these “poor things” on the occupied territories is bringing humanitarian aid to pensioners and caring for homeless animals.

We see how soldiers fall in love, doubt the purpose of their presence at war, and mourn the dead soldiers. The fact that almost all the characters of the film went to kill voluntarily for big money is not reflected upon by the filmmaker. Also, the film does not criticize the current regime or the president. And Putin's face appears for a couple of seconds closer to the end of the film in passing on TV without any author's commentary.

Any commentary from the author, who claims that she spent seven months at the front without permission from the Defense Ministry, does not inspire confidence.

Sonya Vseliubska, Ukrainian, film critic

The main issue with “Russians at War” lies in the inherently subjective nature of the documentary style the filmmaker employs. This approach, known in documentary theory as the "Participatory" mode, is characterized by the director’s personal involvement in the events, shaping the narrative with a deeply subjective perspective. When watching this type of documentary, it’s important to remember that its portrayal can sometimes be far from objective, even bordering on wishful thinking.

This becomes clear within the first few minutes of “Russians at War.” One of the opening lines, which sets the tone for the entire film, is: “It’s been a year since I woke up to the realization that my country started the war.” With these words, the director drives to the "Kievskaya" railway station, where she meets a soldier who escorts her to the front lines.

As Trofimova approaches her subjects, her cinematic style becomes more lyrical. She relies heavily on hand-held cameras, close-ups, and somber music, all enhanced by her narrative voiceover, which reflects her confined, personal observations. Through this cinematic language, combined with her ambiguous political beliefs, Trofimova’s film draws viewers into mediation from the very beginning, aiming to evoke sympathy and empathy for Russian soldiers and the difficult conditions they face.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, sharing an important culture-related story from Ukraine. It's honestly a bit maddening to see that this film about Russian soldiers got made in the first place and that some film critics are defending it. But if you talk to people who actually suffer firsthand from Russia's war, and their allies, you hear entirely different feedback. It's important to note the difference. If you like reading such content, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.