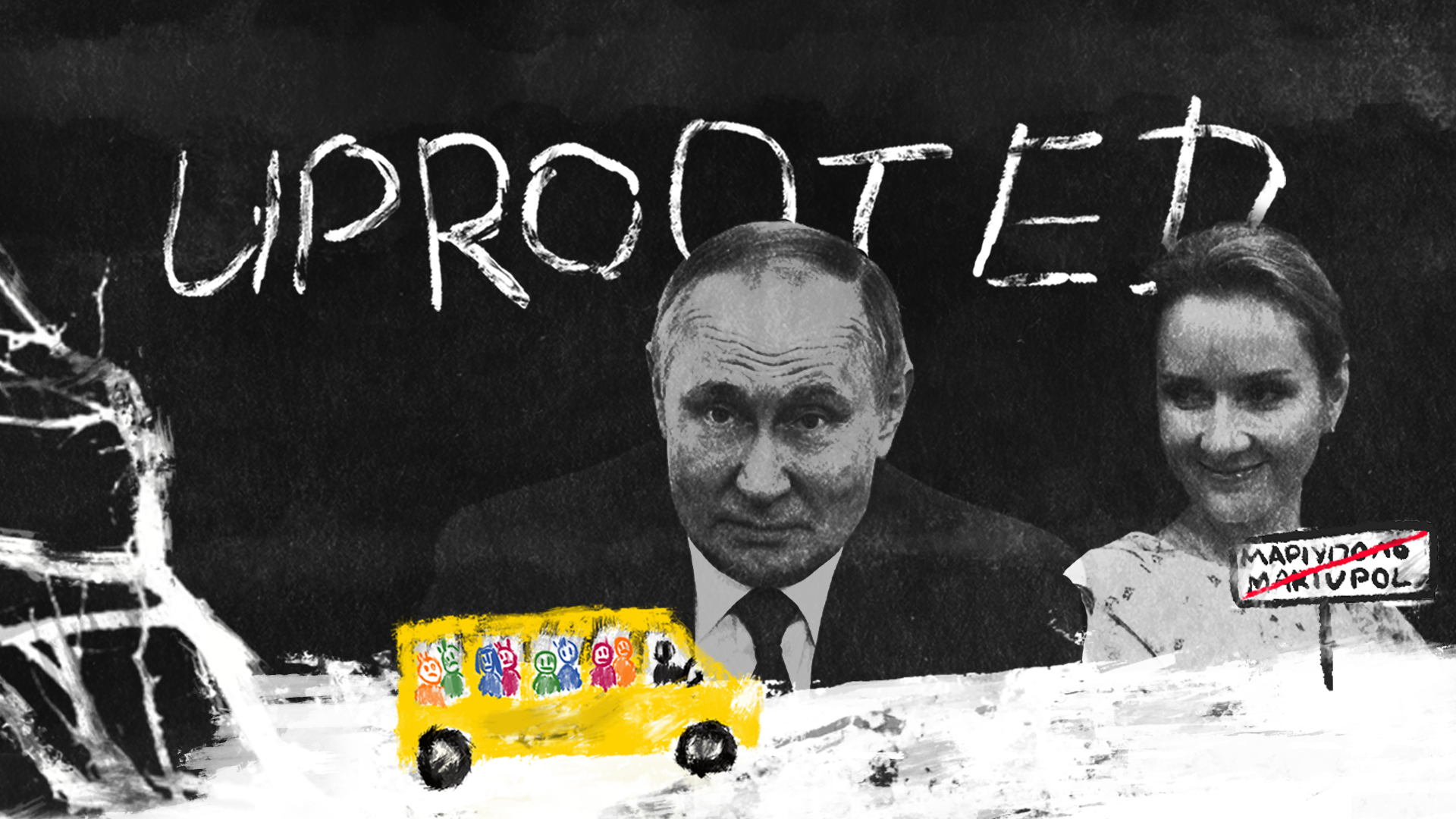

Investigation: After occupying their land, Russia trains Ukrainian children for a lifetime of war

A boy takes aim with a rifle during the “Time of Young Heroes” program in an Avangard defense and sports camp in Volgograd Region, Russia, in a photo published on June 26, 2024. (lageravangard34/VK)

Editor's note: Some names including Oksana's have been changed for security reasons.

Oksana was just 14 when Russia occupied her village, and only 16 when Russian forces began training and indoctrinating her to fight against Ukraine.

At a camp outside Moscow, what was sold as a short vacation was in fact three weeks of intensive military training.

"Sometimes I fainted," she said. "They gave me smelling salts, I got up and kept running with the gun.

"My mom didn’t believe me until I sent her a video of me in uniform with an assault rifle."

Oksana's story is far from an isolated incident, and an investigation by the Kyiv Independent has shone a light on Russia's deliberate and 11-year-long policy of indoctrinating and militarizing Ukrainian children.

Today, an estimated 1.6 million Ukrainian children remain in territories occupied by Russia. Cut off from Ukraine’s education system, they are exposed daily to Russian propaganda, militarization, and pressure to abandon their national identity.

Parents, children, and human rights activists interviewed by the Kyiv Independent say escaping this system is nearly impossible. In occupied territories, the indoctrination begins at school and extends into nearly every aspect of children’s lives.

Pupils are forced to study according to Russian standards, write letters to Russian soldiers, and join youth organizations designed to glorify the army. Some are taught to handle weapons, dig trenches, or operate drones.

Some are even made to exhume human remains from World War II battlefields.

The Kyiv Independent has identified the people who led and taught at the camp where Oksana was trained. Most of them had taken part in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — capturing cities now devastated and under occupation.

Oksana's story

Oksana lived with her parents and four brothers in a quiet village on Ukraine’s southern steppe. After Russian troops occupied the area in late February 2022, the family kept the children at home. Schools reopened under the Russian flag and Russian curriculum, but her parents refused to send their children there.

Soon, soldiers began appearing at their door. They asked when the family would accept Russian passports and when the children would start attending school.

To keep her children out of the Russian-run school, Oksana’s mother had to come up with convincing explanations every time soldiers came to their door — until one day, the threats became explicit.

“They came a third time and said that if we didn’t send the kids to school, they’d take us to an orphanage,” Oksana recalls.

Fearing that the threat was real, Oksana’s mother relented. The teenager was forced to apply for a Russian passport, record herself taking an oath of allegiance, and enroll in a new school that was under Russian control.

The change was immediate. Ukrainian language and history disappeared from the curriculum. Her math teacher began teaching Russian language and history.

Visits from soldiers became part of the school routine.

“The principal came in during class and told everyone to go downstairs, saying we had guests,” Oksana remembers. “There were soldiers in uniform, lots of weapons. They put helmets on us, handed us rifles, showed us how to use them, and taught us first aid.”

Russian servicemen also told students about summer camps in Russia where they could “learn military discipline.” At the time, Oksana didn’t realize she would soon be sent to one — more than a thousand kilometers away.

Indoctrination through youth movements

Kateryna Rashevska is a lawyer with the Regional Center for Human Rights. She works internationally to defend the rights of Ukrainian children affected by the war and by war crimes.

According to Rashevska, Russia’s policies in occupied territories violate the very foundation of international humanitarian law.

Occupation, she explains, is a temporary condition. Therefore, an occupying state is bound by the principle of status quo ante bellum — maintaining the situation that existed before the occupation.

“When we talk about children,” Rashevska notes, “this principle directly affects their education and upbringing.

According to Rashevska, Russia’s imposition of a new state curriculum across occupied territories violates Article 50 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which requires an occupying power to keep children’s education running with local authorities, entrust schooling, so far as possible, to people of the children’s own nationality, language, and religion, and forbid enrolling children in organizations subordinate to the occupier.

Across the occupied regions, schools that reopened were forced to teach according to Russian programs, ban Ukrainian subjects, and introduce “special classes” supervised by police, prosecutors, and soldiers.

Moreover, after the full-scale invasion, Russia changed its laws on education and youth policy, placing a strong emphasis on military-patriotic upbringing and preparing young people for service in the armed forces. Youth organizations have played a key role in pushing this agenda.

Journalists from the Kyiv Independent spent months analyzing the activities of these groups in the occupied territories — including both branches of established Russian organizations and newly created local movements for children and teenagers.

Since the start of the invasion, at least two dozen such groups have emerged across the occupied parts of southern Ukraine, most led by local collaborators who agreed to work with the occupation authorities.

Publicly available records show that these groups organize “patriotic” events for children alongside military recruiters, veterans, and active-duty soldiers.

Seventeen-year-old Ihor (name changed) and his nine-year-old sister Olena (name changed), who spoke to the Kyiv Independent, were also forced to attend school under occupation after soldiers threatened to send them to an orphanage.

Once enrolled, both were drawn into youth organizations created and supervised by the occupying authorities.

“In the occupied territories, they do everything possible to keep children busy with something controlled by Russia.”

Olena was made to join “The Russian Eagles” — a Russian patriotic movement that targets children from elementary school age. Through this organization, students are required to write letters to Russian soldiers and attend meetings with participants of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

In occupied Zaporizhzhia Oblast, “The Russian Eaglets” also launched a project called “Children Heroes of the Great Patriotic War,” where elementary school students made videos honoring Soviet soldiers who fought in World War II.

Ihor became a member of the youth organization “Young South.” Among the activities the organization promotes are painting over so-called “Nazi symbols,” guarding memorial sites ahead of May 9 Victory Day celebrations, and delivering letters from the Russian president to veterans of World War II.

In occupied Kherson Oblast, representatives of the all-Russian military-patriotic organization “Youth Army” (Yunarmiya), together with the local organization “Patriot,” regularly hold paramilitary events for schoolchildren.

At one such event, students practiced military drills, learned to assemble and disassemble Kalashnikov rifles, and took part in air rifle shooting.

In 2024, 50 members of the Youth Army from occupied parts of Kherson Oblast were also involved in excavations of the remains of civilians killed during World War II.

At the time, the organization’s head, Serafim Ivanov, justified the practice by saying that schoolchildren “should learn their history” — one that, he claimed, had been “hidden in Ukrainian schools.”

Participation is often mandatory.

“In the occupied territories, they do everything possible to keep children busy with something controlled by Russia,” Rashevska said.

The 'Warrior Center' — preparing the next generation of soldiers

At her school, Oksana was enrolled in the Movement of the First, one of Russia’s most ambitious youth projects launched in 2022. The first branches appeared precisely in occupied Ukrainian regions.

The organization’s 2024 budget was roughly $210 million. President Vladimir Putin heads its supervisory board. Its director, Artur Orlov, is a Hero of Russia and a former lieutenant colonel who commanded a battalion in the 90th Guards Tank Division during the invasion of Ukraine. Ukrainian prosecutors have indicted members of Orlov’s regiment for committing war crimes.

Oksana recalls how her principal encouraged students to join the organization. “In reality, we had no choice,” she said. “Even those who refused were forced to participate.”

Members distributed aid packages to elderly residents, posed with flags for photos, and cleaned public spaces.

Oksana was also tricked into joining another organization: the Warrior Center for Military and Patriotic Training, created in 2022 by direct order of Putin. While its branches operate in only about 20% of Russia’s regions, the network extends to nearly every occupied region of Ukraine.

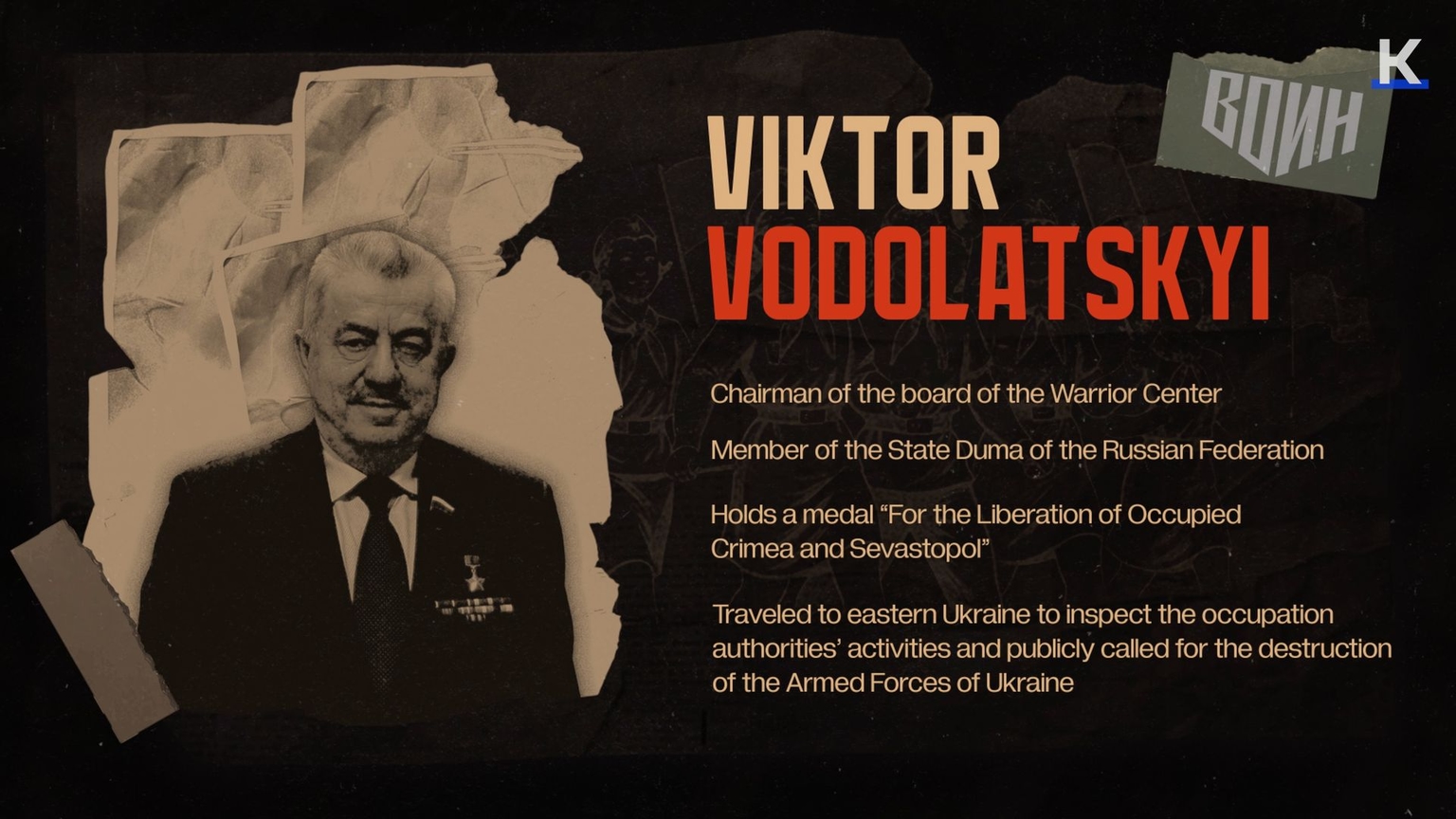

The chair of its supervisory board is Viktor Vodolatsky, a State Duma deputy of the Russian Federation. He holds a medal for what Russia calls the "liberation" of occupied Crimea and Sevastopol.

Since 2022, Vodolatsky has regularly traveled to occupied eastern Ukraine, inspecting Russian-installed administrations and calling for the destruction of Ukraine’s armed forces. The Security Service of Ukraine has charged him in absentia for his anti-Ukrainian activities; several Western countries have sanctioned him.

His deputy and commander of the Warrior Center is Andranik Gasparyan, a colonel in the Russian Armed Forces and veteran of the wars in Chechnya, Syria, and Crimea. His brigade was among the units that invaded southern Ukraine in 2022.

Ukrainian investigators accuse his subordinates of war crimes — including beatings, abductions, killings of civilians, mock executions, and the rape of a minor.

Each summer, the Warrior Center organizes a flagship program called Time of Young Heroes in summer camps across Russia. One of its declared goals is to prepare youth for service in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

For children from occupied parts of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson regions, these take place at the Avangard defense and sports camp in Russia.

'If you want to defeat your enemy — raise his children'

In late spring 2024, as the school year was ending, teachers told Oksana’s mother that her daughter had been offered a chance to spend the summer “resting” at a camp in occupied Crimea.

In reality, she was sent more than a thousand kilometers away — to the Avangard camp in Russia, where the promised vacation turned into three weeks of military training.

“At seven in the morning, we had to wake up. You had five minutes to make your bed, clean the room, get dressed, mop the floor, and go to breakfast,” Oksana recalls.

“Then the assembly — they raised the flag and played the anthem of Russia and of the camp. From 9 a.m., we had lessons in tactics, first aid, communications, how to mine and demine terrain, how to use grenades and dig trenches. After a half-hour break and a meal, more training until evening.”

There was no time for rest. Anyone who overslept faced punishment — squats, push-ups, and minutes of planking.

In an interview on a Russian propaganda channel, camp instructor Pavel Korotov, a representative of the Warrior Center, said the aim of the program was not only to teach children how to handle weapons but also to demonstrate how Russian soldiers use them in real combat during the war against Ukraine.

In practice, the training at Avangard closely mirrors the realities of modern warfare. Among other things, children are taught how to operate drones.

A Ukrainian Special Operations Forces serviceman and instructor with the call sign “Pirnach,” who trains both military personnel and civilians, reviewed the Time of Young Heroes program, as well as photos and videos from the Warrior Center and Avangard, at the Kyiv Independent’s request.

“Some of the training corresponds to what mechanized infantry units receive during standard military preparation,” he said. “Three weeks like that — it’s essentially an introductory course in how a military organism functions.”

The instructors at Avangard were mainly employees of the Volgograd branch of the Warrior Center. The branch’s head, Igor Vorobyov, spent two decades in Russia’s Penitentiary Service before volunteering to fight in Ukraine in 2022. He took part in the assault on Maryinka, a city in Donetsk Oblast that once had 10,000 residents and is now destroyed.

After being wounded, Vorobyov returned to Volgograd and later became the director of the branch. In an interview about the war, he said: “If you want to defeat your enemy — raise his children.”

The Kyiv Independent identified at least 25 instructors under Vorobyov’s command who trained Ukrainian children at Avangard. Most had combat experience and had fought in Ukraine.

Among them was Yegor Sokov, a former fighter of the Wagner Group who fought in Soledar and Popasna — two eastern Ukrainian cities now under occupation. Sokov has been awarded the Order of Courage, as well as a military merit star from the Central African Republic. Sokov now teaches radio communications at the Warrior Center.

Six instructors came from Warrior Center branches in occupied Ukrainian territories. Some were only teenagers when Russia first invaded their hometowns in 2014.

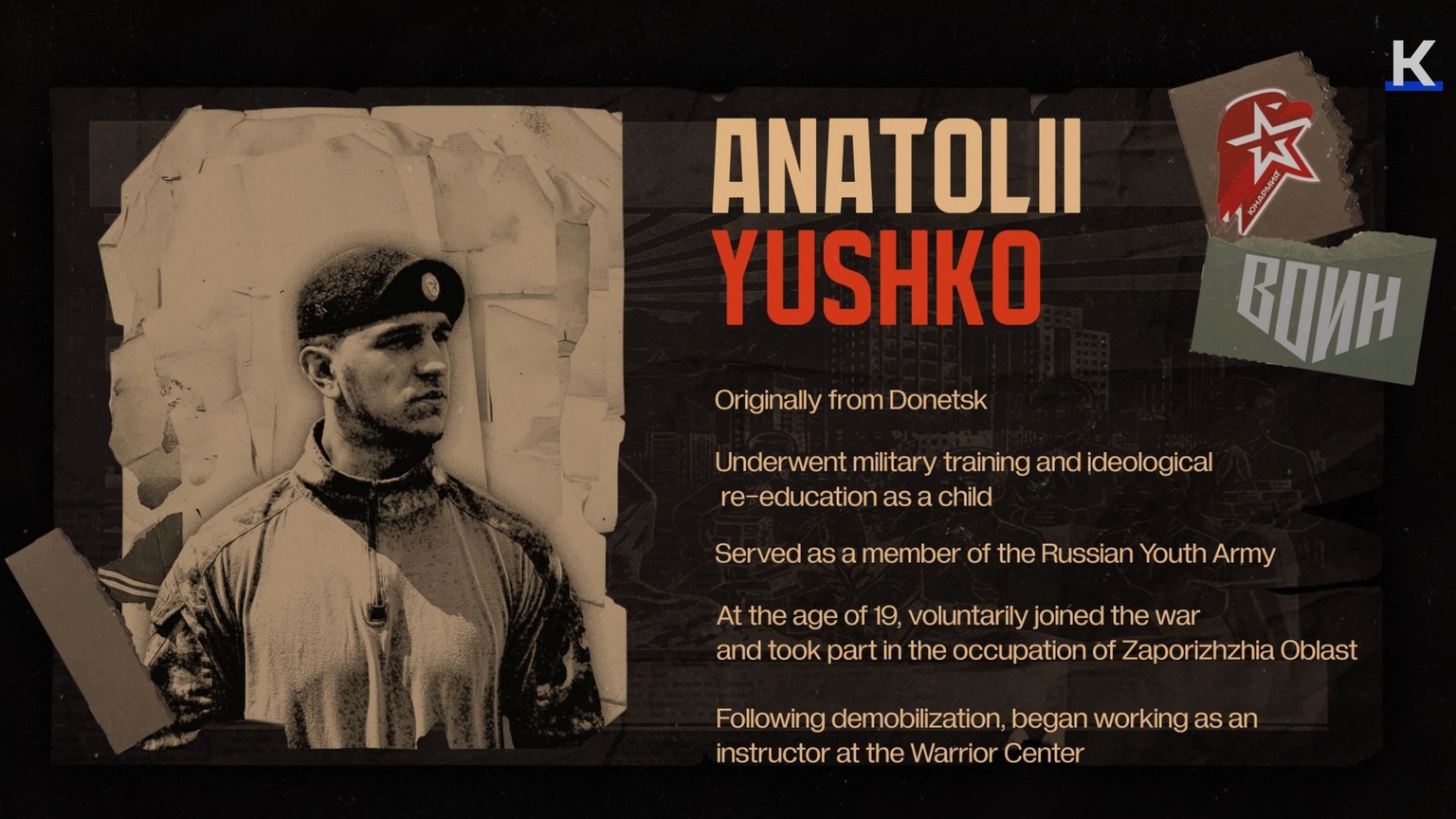

One of them, Anatolii Yushko, was still in secondary school when Russia occupied Donetsk. He joined the Youth Army, another Russian militarized organization. Journalists from the Kyiv Independent received internal correspondence from the Regional Center for Human Rights that involved the leadership of the Youth Army. Originally it was uncovered by the Ukrainian cyber community KibOrg.

The documents show that nearly 1.7 million children are enrolled in the organization, and one in 10 goes on to attend Russia’s military academies. According to Russian officials, about 12,000 Russian Youth Army graduates are already fighting against Ukraine.

In 2022, at just 19, Yushko volunteered for the invasion, taking part in the capture of parts of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. After demobilization, he returned home — to train children at the Warrior Center.

'No longer just about Ukraine'

When Oksana’s three-week training ended, camp officials invited her to stay and teach first aid to younger participants. She refused.

She returned home — still under occupation — and later managed to enroll in a university. In June 2025, she finally escaped to Ukrainian-controlled territory.

In 2024 alone, 1,290 children from occupied Ukrainian regions were sent through the Warrior Center’s military programs.

Researchers at Yale School of Public Health’s Humanitarian Research Lab documented at least 210 locations across Russia and occupied Ukraine where Ukrainian children are subjected to militarization and re-education. The Avangard camp is among them.

Although the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court does not specifically list “militarization of minors” as a war crime, Rashevska and her colleagues are working to establish it as both a war crime and a crime against humanity.

Rashevska said that Russia is raising ideologically conditioned young people from the occupied territories of Ukraine, who could later take part in new acts of aggression beyond Ukraine — in countries like Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, or Poland.

She added that the international community is finally beginning to recognize that this militarization of Ukrainian children poses a serious threat to regional peace and security.

“It’s no longer just about Ukraine,” she said.