How Europe plans to phase out Russian oil and gas, explained

The Duna Oil Refinery, one of the largest in Eastern-Central Europe, that receives Russian oil via the Druzhba pipeline, in Szazhalombatta, Hungary, on May 24, 2022. (Janos Kummer / Getty Images)

In the coming weeks, the EU will decide whether to phase out its remaining Russian fossil fuel imports by early 2027 — or give itself another year.

Whichever deadline it sets, the bloc will face a difficult path to get there. It will have to overcome resistance from some capitals and secure new sources to replace the billion euros' worth of Russian oil and gas still flowing to the EU each month.

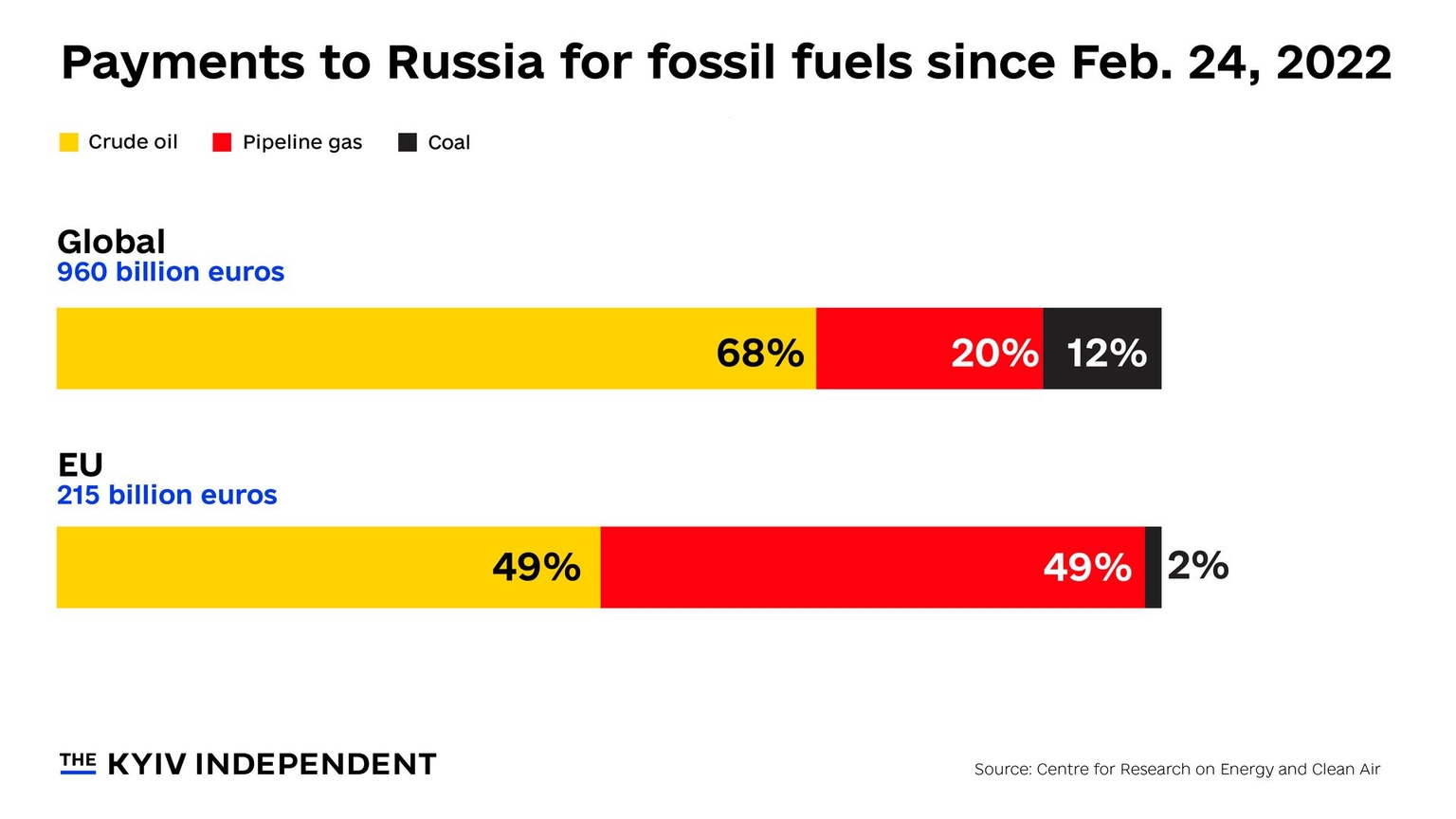

The EU has made substantial progress in reducing its long-standing reliance on Russian energy since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, especially in cutting seaborne oil imports. Gas, on the other hand, continues to account for two-thirds of the bloc’s remaining imports of fossil fuels from Russia.

But how Europe replaces the remaining Russian gas imports depends on the state of the global market for liquified natural gas (LNG), which has played a significant role in substituting pipeline flows from Russia.

Persuading Hungary and Slovakia to give up the cheap flows of Russian oil and gas they continue to import via the Druzhba and Turkstream pipelines will also be key. Both countries have maintained an accommodating stance towards Moscow, repeatedly vetoing sanctions and wringing concessions from the bloc by threatening to do so.

Nevertheless, October saw a concerted effort by the EU alongside the U.S. and U.K. to intensify measures against the Russian energy sector — paving the way for final negotiations of the phase-out plan, known as Repower EU.

On Oct. 22, the U.S. imposed blocking sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil groups, Lukoil and Rosneft, just hours after the EU adopted its first sanctions on Russian LNG imports.

The EU sanctions, which require unanimous reapproval every six months, included a complete ban on Russian LNG starting in 2027. At the same time, the EU is negotiating its longer-term Repower EU legislation that would make the phase-out of Russian oil and gas permanent.

In mid-October, the European Parliament voted for a ban on Russian oil and gas from the start of 2027, while the Council of the EU — which brings together the ministers of its 27 states — backed a later date of January 2028. The two institutions will now negotiate the final timeline.

Pitfalls of the Repower EU plan

The bloc plans to phase out Russian energy under the long-term Repower EU plan by reducing overall energy consumption, expanding renewable generation, and diversifying supplies.

While progress has already been made on all of these fronts, the plan is not without its own shortcomings.

Firstly, high costs have already led European industry to limit energy consumption, and prices remain well above those of the U.S. and China.

Secondly, a shift to renewable energy implies much deeper dependence on China, which exercises a staggering degree of control over the industry — all the way through to minerals like the rare earth metals, exports of which Beijing only recently weaponized, once again, in its trade dispute with the U.S.

Thirdly, securing new supplies of fossil fuels is not without its risks. Since 2022, the U.S. has replaced Russia as the EU’s main source of fossil fuels, but under President Donald Trump has become a less predictable partner.

Trading reliances

The bloc has agreed to increase its imports of American energy even further — to the tune of $250 billion in each of the next three years, under the trade deal struck in July.

The EU remains significantly more reliant on imports of fossil fuels, which account for 58% of primary energy, than other major economies — despite progress in both expanding renewable energy and reducing energy consumption since 2021 — according to a recent Ember Energy report. This cost the bloc some 930 billion euros during the gas crisis of 2021-2024.

While Norway has become the EU’s main overall supplier of natural gas, accounting for a third of imports, mainly via pipeline, the U.S. replaced Russia as the second largest overall supplier this year, and accounted for 24% of overall gas imports in the first quarter of 2025 — providing 53% of LNG imports. Russia’s share of overall gas imports fell to 14% in the first quarter from 19% in the last quarter of 2024.

Imports of Russian LNG have nevertheless remained fairly steady this year, with the EU still Moscow’s main buyer. Despite ample regasification capacity — particularly in Spain, France, and Belgium — the bloc faces global competition for non-Russian LNG, especially from Asian buyers, George Voloshin, an expert on Russian affairs and sanctions, told the Kyiv Independent.

Beyond what could be a fraught winter — depending on the weather — a wave of new LNG supply from the U.S. and Canada is expected to calm the market in 2026. The head of the International Energy Agency recently said that LNG is becoming a buyer’s market as supply expands, reducing prices.

In the meantime, the EU is to resume coordinating firms' purchases of gas "soon," to diversify supplies and obtain more competitive prices, energy commissioner Dan Jorgensen recently said.

Central European headache

Hungary remained the largest EU importer of Russian fossil fuels in September by some margin, spending 166 million euros on oil and 226 million euros on gas. Slovakia was the second largest buyer with oil imports of 145 million euros and gas imports of 62 million euros.

While the Czech Republic drew a line under sixty years of Russian oil imports via the Druzhba pipeline in April, Hungary and Slovakia have shown little inclination to do so — despite the Croatian operator, JANAF, of a pipeline from the Adriatic insisting it can cover the volumes required by Hungarian oil group MOL’s two refineries.

Hungary and Slovakia also continue to rely on gas supplies from Russia’s last operational pipeline to Europe, Turkstream — deliveries via which have risen 7% year on year in the first nine months of 2025.

Not only does the pipeline facilitate ongoing Russian exports, it also undermines European efforts to diversify supplies by flooding the market with discounted gas, which disincentivizes the development of domestic production.

The pipeline reaches the bloc through Bulgaria, which was recently reported to support plans to end Russian gas imports by the end of 2027.

Turkey's deepening ties with Moscow

Longstanding NATO member Turkey has deepened economic cooperation with Moscow since 2022 and has become a significant hub for re-exports of Russian oil and gas to Europe.

The country is now Russia’s third-largest fossil fuel buyer, behind China and India, and the main importer of its refined oil products. In September alone, Turkey bought 2.6 billion euros of Russian fossil fuels, according to the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

As part of the bloc's 18th package of sanctions adopted in July, imports of oil products are to be banned as of January from third countries that are net importers of crude oil, but this far from reliably excludes Russian crude oil, according to a CREA monthly report for July.

Closing these remaining gaps requires not only further sanctions and policy measures, but much stronger enforcement and monitoring.

"Even if the Repower EU legislation is brought forward, there still remain a few concerns," CREA energy analyst Luke Wickenden told the Kyiv Independent.

"Most notably, the controversial Article 15, reportedly introduced at Spain's request, could empower member states to ask for temporary lifting of the ban in case of emergency — though what exactly constitutes an ‘emergency’ remains undefined."