Forget Ovechkin and Washington. The Kyiv Capitals are playing for the survival of Ukrainian hockey

...and they're really good.

Fans and players celebrate the Kyiv Capitals' 3-2 victory over HC Kremenchuk in the first game of the Ukrainian national championship series in Kyiv, Ukraine, on March 26, 2025. (Chris Jones / The Kyiv Independent)

It's late in the second period of game four of the Ukrainian national hockey championship on April 2, and the upstart Kyiv Capitals, only in its second season, leads against established Hockey Club (HC) Kremenchuk and its star-studded roster.

The Capitals captain, Serhii Chernenko, steals the puck and sends it behind the net to his teammate, a second before Kremenchuk forward Vladyslav Braha slams him against the boards.

The ref blows his whistle, but it’s not for a penalty. An air raid alert signaling a potential Russian attack brings the high-stakes game to a halt, a stark reminder of Russia’s war happening outside the rink. Fans file outside the Kremenchuk Iceberg Arena in Poltava Oblast, a five hour drive south of Kyiv, stretching their legs and waiting for the threat of ballistic missiles to abide.

Playing ice hockey in Ukraine today is unlike competing in any other hockey league worldwide. Besides the game interruptions, the sport heavily relies on civilian infrastructure: No ice rink, no hockey.

Ice rinks haven't escaped Russia’s campaign to bombard Ukrainian civilian sites. From 2022 to 2024, 725 sports facilities have been damaged or destroyed in Ukraine. Some of Ukraine’s most celebrated ice rinks lie in ruins.

Among them is Kherson's Favorite Arena ice rink, which had already been damaged by Russian attacks, but was completely destroyed on April 16 by a direct strike.

Rinks also require electricity for refrigeration and are more challenging to build – and rebuild – than facilities for most other sports. Russia has damaged more than 63,000 energy infrastructure facilities in the past three years, according to the Energy Ministry, leading to long-term blackouts particularly during winter months.

The impact of war on Ukrainian hockey is embodied by the banners hanging from the rafters over Kremenchuk’s Iceberg Arena, where the logos of only five professional teams are represented in this year’s professional league.

Missing is the powerhouse team HC Donbas, winner of five of the previous six Ukrainian hockey championships before the unfinished 2022 season was interrupted by Russia’s full-scale invasion. HC Mariupol is also missing, whose brand-new home ice rink was unveiled by President Volodymyr Zelensky in 2020 and had “amazing” ice, players who skated there recall. HC Kramatorsk, who played one complete season in their yellow, black, and white uniforms before Russian troops abruptly ended their second, is also absent.

All three teams were based in Donetsk Oblast, where Moscow now controls more than 70% of the territory. Heavy Russian attacks blanket the remaining 30%.

It was against this backdrop that Kyiv Capitals CEO Anastasia Zimina and her father, former hockey player Eugene Zimin, decided to create and fund a new team in early 2023. It took about six months, she estimates, to go from idea to reality.

“We had no plans before the war whatsoever” to form a new team, Zimina tells the Kyiv Independent. When it was clear that Russia was trying to erase Ukrainian people and culture, establishing a new team felt like one way to “defy” a historical pattern of cultural losses during war and have something to grow instead, she said. “The main idea was to give back and restore Ukraine through sports.”

The story of the Kyiv Capitals is more than just one of a team born during war, with players who have survived Russian occupation and practices held on melting ice, in the dark, after Russian missiles knocked out the city’s power.

It’s the story of a team playing with such energy that once the puck drops, it’s not about the war — it’s about the team, it’s about the ice, it’s about Capitals’ forward Sevastian Karpenko slapping the puck past the goalie’s right hip six minutes into overtime at their home rink, and the standing-room-only crowd cheering so loudly that you can feel the building vibrate through the cement sidewalk outside.

From ponds to the global stage: A century of Ukrainian hockey

The first Ukrainian ice hockey match took place more than a hundred years ago, on a pond rink in Lviv in 1905. Spectators unfamiliar with the sport drank hot tea and mead and “liked what they saw,” according to a news report from the time.

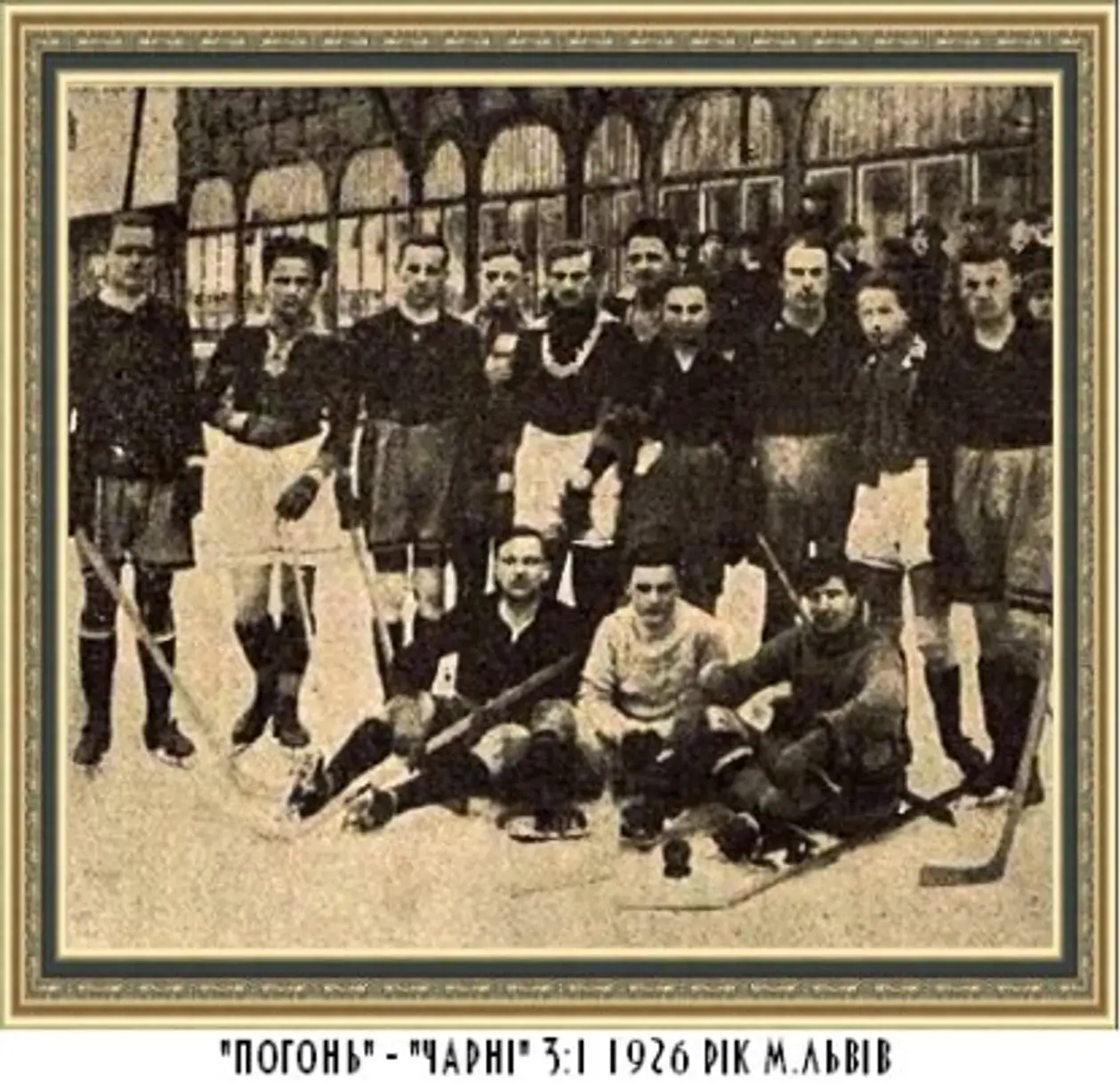

In 1910, Ukrainian professor Ivan Bobersky published the first Ukrainian-language rules of ice hockey. The first local championship, held in 1926, involved eight Lviv-based teams, including two Jewish clubs. The victor was Pohon, winning 3:1 against Charny.

Like much of Ukrainian culture, ice hockey suffered when the Soviet Army took over parts of Europe during World War II. In one dramatic incident in 1940, Soviet troops occupied an area in present-day Chernivtsi Oblast, which was, at the time, an ice hockey hub and part of Romania. The local players were labeled “nationalist bourgeoisie” after defeating the Red Army’s team several times, forcing most of the athletes to emigrate to evade arrest. Other teams also dissolved or were renamed.

Nonetheless, Ukrainians continued to play ice hockey and produce world-class athletes. By the 1950s, the Ukrainian SSR hockey league was among the most competitive in the Soviet Union.

After the Soviet Union fell in 1991, Ukrainians also made a name for themselves globally by playing in the National Hockey League and European leagues. Ruslan Fedotenko and Dmitri Khristich are among Ukrainian NHL players who have won the Stanley Cup. One of the all-time greatest hockey players, Wayne Gretzky, has Ukrainian ancestors.

A sport and country under attack

When the Kyiv Capitals offered team captain Chernenko a spot, he didn’t know what to expect from a team with no track record. “I and the coaching staff probably had some doubts, but everything worked out fine,” he said.

Chernenko, the most experienced player on the team at 41, first laced up his skates at six years old, when his father walked him and his older brother to an ice rink a few minutes from his childhood home in Kyiv.

He represented Ukraine on the global stage several times as part of the youth national team before playing on the country’s 2011 national team, which won bronze at the D1 World Championship. He later played on Romanian teams before returning to play in Ukraine.

On the ice, Chernenko is a playmaker, focused on finding open players and disrupting defenders, racking up 23 assists and seven goals in the regular season. His discipline and experience lead some to view him practically as an extra coach, and he can often be seen mentoring teammates on and off the ice.

"Arenas are destroyed. There are fewer teams, and so, fewer players. Children are unable to participate."

Serhii Chernenko, the captain of the Kyiv Capitals, sits for a portrait at the Shalett ice rink in Kyiv, Ukraine on April 10, 2025. (Chris Jones / The Kyiv Independent)

With decades of hockey experience, Chernenko has watched how the country’s competitiveness has suffered under attack.

“Ukraine was once in the top division, there was a lot of competition, and there were strong players. They played abroad and within the country,” recalls Chernenko. “Then, war. Arenas are destroyed. There are fewer teams, and so, fewer players. Children are unable to participate.”

Any professional Ukrainian hockey player can rattle off the names of the destroyed arenas.

The first to go was Druzhba in Donetsk, ransacked and torched by armed militants during the Donbas War in March 2014. HC Donbas was forced to relocate from the rink to the Altair Ice Arena in Druzhkivka, also located in Donetsk Oblast.

Then the full-scale invasion began, and that rink, too, was destroyed by a Russian X-55 cruise missile.

Over the course of the war, rinks in Mariupol, Siverskodonetsk, Kherson, and three rinks in Kharkiv — including an Olympic training base that hosted two hockey teams — have also been ruined by shelling or occupation.

Since the full-scale invasion, the number of professional hockey teams in Ukraine has halved.

“For the level (of competition) to grow, we need the arenas that have been destroyed. We hope that they will be rebuilt,” Chernenko said.

‘The problem is people and children are leaving’

An even more threatening issue, say players, is the talent that has left. Ukraine’s population has fallen by an estimated 10 million since 2022 as Ukrainians flee the war abroad or are killed.

Not only is Ukraine lacking the key hockey-playing demographic of fighting-age young men — it’s also short on the next generation of up-and-coming players.

“A lot of kids have left. A lot,” says Kyiv Capitals Sports Director Oleg Grushetsky. The Kryzhynka hockey school, he notes, a youth program that partners with and shares a rink with the Capitals in Kyiv, enrolled around 350 kids before the full-scale invasion. Today, it’s dropped down to 122.

Approximately 60% of Ukraine’s hockey-playing youth have been forced to abandon their homes, estimates Ukrainian Hockey Dream, a charity that supports youth hockey.

Ukraine once boasted one of the top youth hockey boarding schools in Europe, located in Donbas. The competitive program attracted players from outside Ukraine who lived together and went to school together, training in hockey before and after classes.

“We had everything. I hadn’t seen anything like it anywhere else in Ukraine,” says Mykyta Oliynyk, a rising left-handed forward on the Capitals team who trained there from ages 13 to 16. “It was at a very high level. There were many foreigners, guys from Russia and Moldova.”

When he was 16, the war in Donbas began, and Oliynyk left the school to complete his training in Kharkiv, where he grew up. “I’m lucky that I had somewhere to go,” he says.

Oliynyk, 26, led the Ukrainian league last year for the most assists in the Capitals’ inaugural season. His skating skills and speed point to top-tier training, which sports director Grushetsky attributes in large part to his experience at the now-closed Donbas Academy.

“The problem today is people are leaving, children are leaving,” says Grushetsky. “I see the main mission of this whole project — all of this, our Ukrainian hockey — is to create conditions to keep people here and persuade them to return.”

Attracting talent from abroad

Recruiting foreign players is tough but not impossible.

One of the fastest players on the ice is Sam Hu, a Canadian-Chinese forward who previously played in the Kontinental Hockey League and East Coast Hockey League. He joined the team with just two months left in the season but has already become one of the standout players, outskating defenders on three-to-one breakaways.

Hu was looking for a new opportunity when a former coach connected him with the Capitals, making him the team’s fourth international player.

He had never stepped foot in Ukraine before the team brought him on board but finds himself “proud and impressed” by the resilience of the people he’s met.

When asked whether he hesitated to come to Ukraine during the war as other foreign players have, he replies, “To be honest, I wasn’t thinking too much about anything else. I just considered the hockey.”

The style in Ukraine is more free-flowing than in other leagues he’s competed in, he says, with less emphasis on set plays and star performers. “It’s not as system-oriented as some other places I’ve played. When it’s a little more unpredictable, it can be a little more exciting.”

“I have not had this much fun coming to the rink in probably five or six years,” Hu adds. “A lot of it is how the players treat each other. There’s a good culture on this team.”

‘Russians, we did it’

When the Kyiv Capitals make it to the playoffs against Odesa Storm on March 15, just over a dozen loyal fans make the trip to the game in Odesa, around 274 miles (441 kilometers) from Kyiv. On the official game livestream, you can hear them chant a three-beat rhythm of “Ca-pi-tals.”

Among them are Albina Shatokhina and Maria Filinchuk, two teenage figure skaters who never miss a home game and train at the same rink as the Capitals.

“Everyone should understand that it is very difficult to train now because of the air raids and blackouts,” Shatokhina tells the Kyiv Independent later in Kyiv. “Despite the war, they are still training and trying to improve Ukrainian hockey.”

“And it’s working,” Filinchuk adds. “A lot of people have gotten to know this team last season.”

With the game tied and three minutes left, Capitals forward Andrii Kryvonozhkin wrestles the puck free behind Odesa’s net. He passes it to Oliynyk, who quickly passes through the Odesa defenders to Karpenko for a one-tap goal. The Kyiv fans erupt into cheers over what will be the game-winning goal, clinching the team a spot in the finals. When the buzzer sounds, the rest of the team pours onto the ice in celebration.

“The only thing worth remembering is Russians did all this.”

Three days later, Russia announces that Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump have discussed organizing ice hockey games between the two countries — widely seen as a political concession to Russia. Russia and Belarus have been banned since 2022 from competing in international hockey competitions over the invasion of Ukraine.

The spotlight on the intersection of politics and ice hockey has only intensified in recent weeks because of the other Capitals — the Washington D.C. team playing on the other side of the globe.

After Washington Capitals player Alexander Ovechkin surpassed Wayne Gretzky’s record of 894 goals scored in the NHL on April 6, Ovechkin’s public friendship with Putin sparked headlines and criticism from Ukrainians and pro-Ukrainian NHL fans. The Russian player celebrated his victory, cheering, “Russians, we did it.” Russia’s propaganda machine quickly seized on the statement, echoing it across state television and pro-war social media channels.

The Kyiv Capitals Telegram channel responded by posting a video pairing his celebration with photos of Ukrainian sports stadiums reduced to rubble, adding, “The only thing worth remembering is Russians did all this.”

‘Everyone has his own story’

“Sports have always been politics,” says sports director Grushetsky. “Because a sports team is people and fans, you have influence over them through sports.”

But the Capitals players don’t need anyone to explain this to them — they’ve lived it.

“We have Valentyn Sirchenko — his home is in the occupied part of Kherson Oblast, which means he has nowhere to return to,” says Grushetsky.

Sirchenko, playing in his second season for the Capitals, is one of the team’s more aggressive defenders, having racked up quite a few penalty minutes this season.

Grushetsky names other players and how the war has touched them.

There’s Deniss Berdniks, a Latvian who is tied with Oliynyk for most assists this regular season. When the full-scale invasion began on Feb. 24, 2022, he was playing for HC Kramatorsk and experienced attacks on the city. He returned to Latvia, but came back to Ukraine to play in the Capitals’ first two seasons.

There’s forward Mykola Dvornyk, who came up through the Kryzhynka hockey school and racked up many points for the Capitals last season before being sidelined by a shoulder injury this season. He survived occupation in Kherson, where Russian troops held the city for 256 days, harassing, torturing, and killing residents.

There’s Danylo Tyshchenko, a tall, athletic forward who also trained within the Donbas system in Donetsk and debuted with a strong performance for the Capitals last season. He, too, lived under occupation in Kherson.

There’s Denys Plesovskykh, one of the youngest on the team at 18, still building weight and strength to compete with the older players but already scoring three goals in the regular season.

Oleksandr Valkun, born a month earlier than Plesovskykh, is also building his strength but boasting goals as well and showing a clear hockey instinct.

Both teens have fathers who served in the war.

“Everyone has his own story,” Grushetsky says. “And then there’s the guys in all the other clubs, too.”

‘Hockey is medicine’

While searching for a team identity, the goal was to be “down to earth and approachable,” CEO Zimina says.

In lieu of tickets to their home games, the Kyiv Capitals request a Hr 100 donation to the military, the equivalent of $2.46.

Maksim Makarov, a 15-year-old who plays for the Kyiv Capitals’ junior youth team, waits outside the rink after games in the low light, snagging photos with some of the players as they carry their equipment out of the rink.

“I’ve been a fan since the Kyiv Capitals were founded. I don’t miss a game here,” he says. “I can’t even think of my life without hockey.”

Like the team, Makarov first began playing hockey after the invasion began, improving from season to season.

“Hockey, for me, is medicine. To not think about my problems. Escape real life. Be happy on the ice. Enjoy every moment,” Makarov says, as the low tone of yet another air raid alert began to wail in the distance.

'War eats emotions'

As the Kyiv Capitals take the ice for the final game of the championship series on April 11, the home arena crowd has been standing room only for a full hour before the first puck drop.

With less than a minute and a half left in the game, the Capitals are up 1-0 but the penalties are racking up. With one player already in the penalty box, another penalty sets Kyiv down two players on the ice. Kremenchuk pulls their goalie to bring out another skater — it’s three on six. Nazar Boiko, a 19-year-old goalie who has blocked a dazzling number of shots for nearly an hour of ice time, sends the crowd into a roar chanting his name with each miraculous save.

Then, with 26 seconds left in the game, Kremenchuk dribbles the puck into the net. The score is tied, sending the national championship into sudden-death overtime.

“We've been through so much this season.”

Any professional sports team in the world would feel proud of making it into overtime in game seven of the championship series in their second season as a team. But when Kremenchuk scores after three and a half minutes of overtime, the Capitals players look exhausted.

As HC Kremenchuk players celebrate on the ice, the packed rink begins to chant, “Ca-pi-tals, Ca-pi-tals,” as fans waved their team scarves and bang their fists on the glass to show their support for the team.

“We have been through so much this season,” an emotional Grushetsky says after the game.

As fans stream out of the arena, kids and adults in Capitals gear wait outside the locker room for players to pose for photos and sign hand-made posters. CEO Zimina greets two Ukrainian soldiers on their way out, both leaving with smiles. Another soldier on crutches limps out of the rink grinning.

Before their heart wrenching overtime loss, team captain Chernenko explained what drives him and the rest of Ukraine’s professional hockey players. “We play for the fans. I see the reaction of my family, my friends, acquaintances, all these hockey communities, the feelings they get watching our matches,” Chernenko told the Kyiv Independent.

“War oppresses and eats emotions. People’s lives have changed a lot, but when they have the opportunity to get out, watch hockey, and feel these emotions, it deeply affects them.”

Note from the author:

Hi, I’m Andrea Januta, the author of this piece. Thank you for reading. As a writer living in Kyiv, I’m always trying to share stories not only about the country’s challenges, but also about the fabric of Ukrainian society that so many are fighting to preserve — from sports and religion, to bird watchers and businesses. It’s meaningful but difficult work. If you’d like to support the Kyiv Independent’s ability to tell these stories from Ukraine, please consider supporting our work by becoming a member.