Explainer: 38 years after Chornobyl, Ukraine relies on nuclear for more than half its energy production

A general view shows the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, situated in the Russian-controlled area of Enerhodar, seen from Nikopol, Ukraine on April 27, 2022. (Ed Jones /AFP via Getty Images)

Thirty-eight years after the Chornobyl disaster, Ukraine’s nuclear industry continues to produce around half of Ukraine’s power output and remains vital to keeping the country functioning.

The share of energy output in Ukraine that comes from nuclear power is the third highest in the world after France and Slovakia.

Amid ongoing attacks on the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the threat of a new nuclear accident in Ukraine remains elevated and has brought an unprecedented level of attention and involvement from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

After the seizure of the Zaporizhzhia plant by Russian forces in March 2022, the other three Soviet-era nuclear power plants remain under Ukrainian control. Compared to the devastation wrought on thermal and hydroelectric power production by Russian strikes, the war’s effect on these three plants has been less severe and their production has remained relatively resilient.

With Ukraine’s energy infrastructure under attack, Ukraine has announced that further nuclear development will be a key focus in 2024. Already, construction has started on additional reactors at the Khmelnytskyi Nuclear Power Plant to increase its output.

“The construction of new power units is very important for the country, because nuclear energy remains an island of stability,” Petro Kotin, the head of Energoatom, the state-owned company responsible for Ukraine’s nuclear plants, said earlier this month.

Crisis at Zaporizhzhia

The largest impact to Ukraine’s nuclear production since the beginning of the war has been the seizure of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the largest nuclear power plant in Europe. The plant’s conditions are also the current biggest threat to nuclear safety.

The plant, located in the town of Enerhodar in Zaporizhzhia oblast, was captured by Russian forces shortly after the full-scale invasion began. Since September 2022, it has not supplied energy to the Ukrainian power grid.

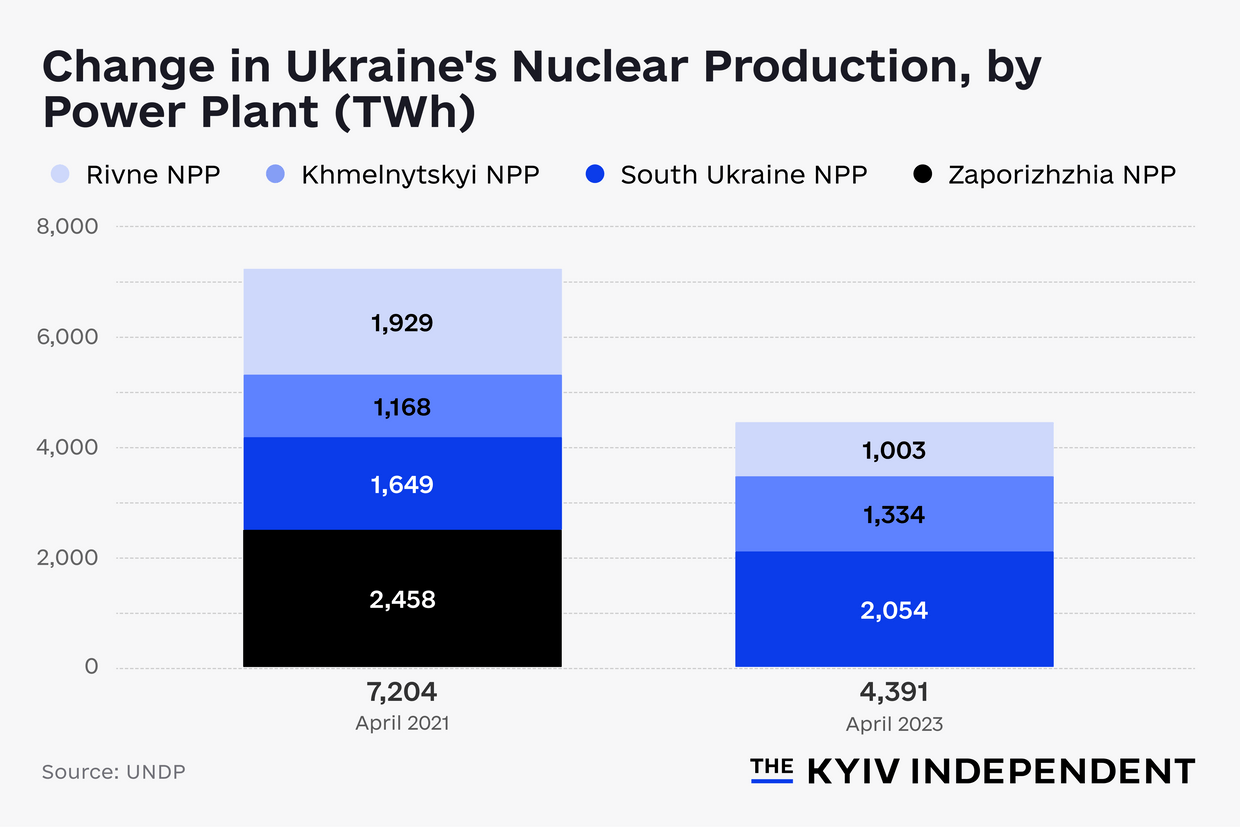

In early 2022, the Zaporizhzhia plant had been responsible for 43% of nuclear power generated by Ukraine, according to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) figures. However, due to reductions in other types of power generation – such as from the recent strikes that have crippled thermal power production – nuclear power is still around half of Ukraine’s total power generation despite losing Zaporizhzhia’s contribution.

Fears of a nuclear accident or sabotage have spread across Europe since its capture. Last year, Ukraine carried out large-scale exercises to prepare an emergency response in case of a Russian attack on the plant.

“The main purpose of Russia at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant is military control, not to safely and securely operate it,” Oleh Korikov, the head of the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine, told the Kyiv Independent in an interview.

After more than two years of military occupation, the equipment and safety at the plant has significantly degraded from a lack of proper maintenance and repair as well as incompetent and illegal Russian staff, he added. The inspectorate was also forced to withdraw its supervisory staff for their protection.

Although the reactors are currently shut down, they still require access to water and external power to maintain a safe core temperature and to operate safety measures. Power outages have periodically cut electricity to the plant, forcing it to rely on backup generators at least eight times, according to the IAEA.

The destruction of the Kakhovka dam in June 2023 also renewed fears around the plant’s access to water, since water from the dam’s reservoir was previously pumped to the plant for cooling. However, the plant has a separate cooling pond whose water levels are currently stable, according to Energoatom.

“As long as the war is ongoing and there are hostilities and shelling from the Russian side, the threat will remain,” Korikov said. “All nuclear power plants in the world were designed and built with the concept that they would be operated in peaceful conditions.”

To respond to the heightened threats, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has deployed rotating staff to the plant since September 2022 to provide technical support and monitoring. However, the staff have been denied access to some areas of the plant.

The IAEA began recording manual readings of the radiation situation near Zaporizhzhia for its international database, after the automated monitoring system at the plant was disconnected last year.

Because of safety concerns, the IAEA in September adopted a resolution demanding Russia immediately withdraw from the power plant, and warned of a “major escalation” following at least three direct strikes on the plant earlier this month, the first such strikes in over a year.

In the shadow of Chornobyl

The memory of the nuclear meltdown at Chornobyl looms large over the current crisis at Zaporizhzhia.

After one of the reactors at the Chornobyl power plant exploded on April 26, 1986, vast amounts of radioactive material were released into the atmosphere. For years following the incident, around 600,000 soldiers, firemen, cleanup workers, and residents continued to be exposed to radiation. Some historians credit the response to Chornobyl and cover-up by the Soviet Union government in Moscow as accelerating Ukraine’s exit from the USSR and its collapse in 1991.

Today, an uninhabitable exclusion zone surrounds the former nuclear power plant, and, up until the war, the site operated as a tourist attraction.

Chornobyl was occupied for several weeks by Russian forces in the initial phase of the full-scale invasion before they withdrew in March 2022. Though Chornobyl’s reactors are decommissioned, there are still active projects at the site related to management of radioactive waste, spent nuclear fuel, and sources of ionizing radiation.

“During the occupation, we (the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate) were unable to fulfill our control and supervisory functions due to the physical impossibility to get into these enterprises,” Korikov said.

The plant at Zaporizhzhia is more powerful than the Chornobyl plant, raising fears that a catastrophe could be far more damaging. However, the plant has stronger modern safety features, as well as a longer lead-time to resolve issues in case of power outages due to the shutdown state of its reactors.

Nuclear production away from the front lines

With the six reactors of the Zaporizhzhia plant in a state of shutdown, nuclear production has fallen on the nine reactors at Ukraine’s remaining three plants, which are situated further from the battle lines.

The three plants – Pivdennoukrainsk (South Ukraine), Khmelnytskyi, and Rivne – were also forced to briefly use backup generations after all three sites lost power in November 2022, but have mostly maintained their production throughout the war.

“Nuclear facilities have suffered the least attacks and destruction of infrastructure,” Olena Lapenko, general manager for security and resilience at the Ukraine-based DiXi Group think tank, told the Kyiv Independent in response to written questions. “However, these are very large power nodes, the disruption of which has a significant impact on the entire power system.”

“We understand they are better protected than other energy facilities, but the strictest safety requirements for the operation of nuclear power plants are practically impossible to meet if affected by military operations,” Lapenko added.

Because of the high stakes of a potential nuclear accident, the IAEA has maintained a presence at these three power plants since January 2023 and the decommissioned Chornobyl plant.

“The constant presence of specialist inspectors at all five reactor sites is unique to Ukraine; staff rotate regularly at all sites,” the IAEA said in a statement to the Kyiv Independent.

In addition to the IAEA’s on-site actions, it has facilitated an international assistance package to help Ukraine secure its nuclear safety, and has kept the world informed on the status of Ukraine’s nuclear facilities with more than 220 update reports since the beginning of the conflict, as well as multiple briefings to the UN General Assembly and Security Council.

The IAEA’s efforts include helping provide medical supplies and assistance to Ukraine’s nuclear workers and arranging delivery of equipment such as communication systems to Ukraine’s authorities.

Ukraine had already shifted its nuclear infrastructure in response to Russian aggression prior to the full-scale invasion. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of Donbas in 2014, Ukraine began using fuel from the American company Westinghouse at its nuclear facilities, rather than the Russian-produced fuel that was used previously.

And, despite the war, Ukraine opened a new facility for storing spent nuclear fuel in 2022, furthering its energy independence from Russia. Contracts for the site were signed in 2005 with U.S.-based Holtec International, though construction only began in 2017 in the Chornobyl exclusion zone.

According to Energoatom, the site will save Ukraine $200 million each year, which previously was paid to Russia for storing and transporting used nuclear fuel.

Future nuclear expansion

With no clear end in sight to the attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure, the government is seeking to diversify and expand its energy industry.

Construction of two new nuclear reactors at the Khmelnytskyi Nuclear Power Plant began earlier this month, which will be the first reactors in Ukraine built using more modern U.S. technology rather than relying on modernized Soviet-era technology used currently. Two more are planned to begin construction later this year to make up for the loss of energy from Zaporizhzhia, according to Energy Minister Herman Haluschchenko.

Once completed, the Khmelnytskyi plant is projected to overtake Zaporizhzhia’s plant as the largest nuclear power plant in Europe.

Ukraine ultimately plans to build nine total units in the country using U.S. technology, according to government decisions and memorandums signed between Energoatom and Westinghouse.

As part of an effort to seek foreign partnerships and investment for further development, Ukraine has also begun reforming Energoatom. While the company will remain fully owned by the state, a law passed last year means the company is introducing a supervisory board and international management standards to increase oversight and transparency.

However, the focus on nuclear energy has tradeoffs.

In addition to safety and environmental concerns, costs for disposal and storage of used fuel can be quite high, while building new plants requires high upfront costs and lengthy implementation, Lapenko of DiXi group noted. “Although it is believed that electricity produced at nuclear power plants is the cheapest one, this is far from the case.”

And, growing the nuclear sector is at odds with the government’s goal of decentralizing its power supply, she said. “Given the permanent threat of the aggressive Russian Federation, again betting on large, powerful generation nodes, even nuclear ones, looks quite risky.”