Haunting Ukrainian novel explores time, trauma, and identity

In the midst of a full-blown agoraphobic episode, the unnamed narrator of Tanja Maljartschuk’s novel “Forgottenness,” becomes engrossed in reading old newspapers. Asked by her increasingly concerned partner what she’s looking for, she simply tells him: “I want to understand what time is.”

“Time consumes everything living by the ton, like a gigantic blue whale consumes microscopic plankton, milling and chewing it into a homogenous mass, so that one life disappears without a trace, giving another, the next life, a chance,” she confides in the reader. “Yet it wasn’t the disappearance that grieved me the most, but the tracelessness of it.”

During this process, the narrator comes across an obituary for historian and political figure Viacheslav Lypynskyi. Unaware of his legacy, she dives deeper into his background, cultivating a growing fascination with this forgotten figure from late 19th and early 20th century Ukraine.

The alternating chapters of the novel, now available in Zenia Tompkins’ captivating English translation, weave Lypynskyi’s life trajectory with the narrator’s, exploring Ukrainian national identity and the country’s struggle for independence over the past century.

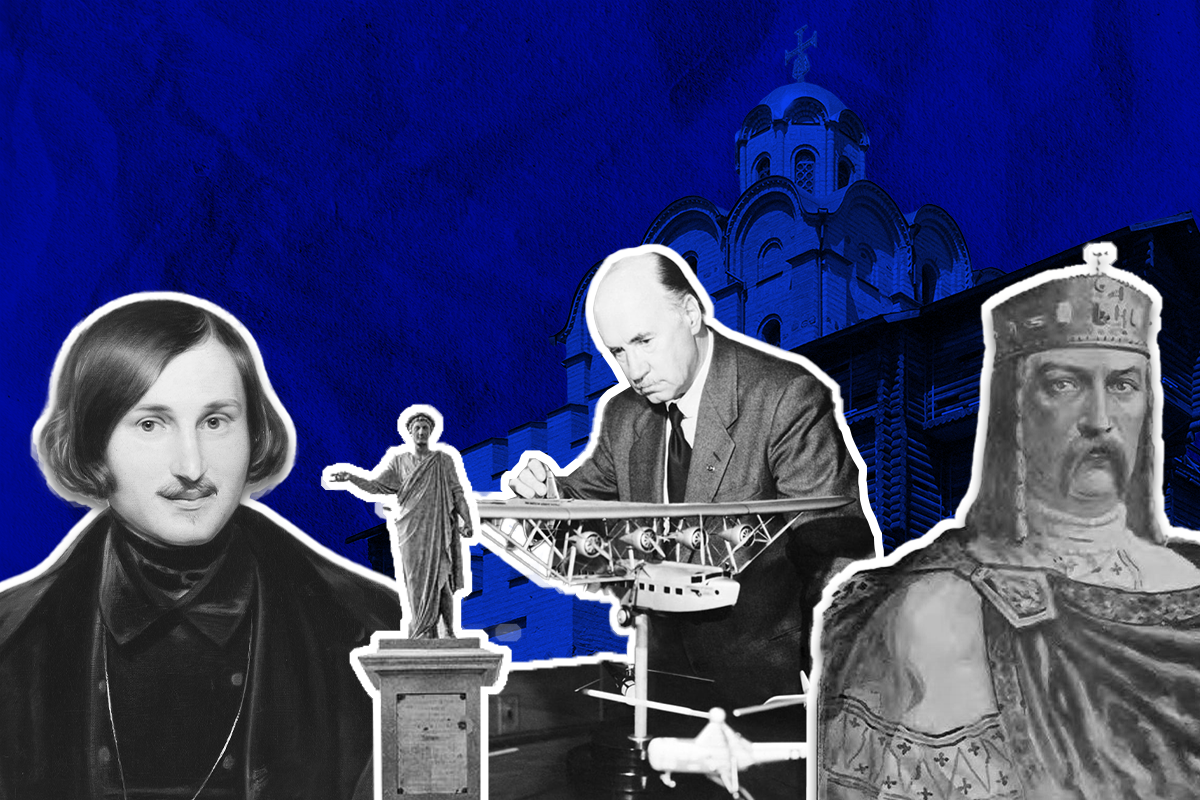

Lypynskyi, born in 1882 in the village of Zaturtsi in present-day Volyn Oblast, Ukraine, hailed from a family of Polish nobles. The village was then part of the Russian Empire. To the confusion and dismay of his family and later his university classmates during his studies in Krakow, he declared from a young age his wish to be called Viacheslav instead of Waclaw, the original Polish spelling of his name.

Lypynskyi spoke Ukrainian and identified himself as Ukrainian at a time when the idea of Ukrainian statehood was a dream and an enigma to many. In the Russian Empire, it was also criminal—there were periods when the use of the Ukrainian language in print was banned by authorities which endeavored to see it confined to being a “peasant tongue” and little more: “Routine searches had taught the custodians of Ukrainian dictionaries to pass them down from hand to hand at the slightest suspicion of yet another shakedown. Aristocratic families could lose privileges for the use of Ukrainian in the home.”

In the early 20th century, the push for Ukrainian statehood coincided with the end of World War I, the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires, and the eventual rise of the Bolsheviks to power. It marked one of the most tumultuous yet pivotal phases in modern Ukrainian history, and Lypynskyi was among those who believed that his own vision for the future would safeguard Ukraine's destiny.

Lypynskyi, much like the unnamed narrator, was fueled by ideas that have been “consumed” by time. He was convinced that only a Hetman – essentially, a monarch – could rule Ukrainians, regardless of their diverse backgrounds and social statuses. While Ukrainians had a long history of resistance, not only against Russia, he maintained that they lacked a unifying idea to rally behind:

“By using traditional Ukrainian statehood — of which the Cossack Hetmanate of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was the only example in the history of the Ukrainian people — as a theoretical basis, such an idea could be created.”

The Cossacks formed an independent military state, also known as the Hetmanate, that lasted from the mid-17th century until it was destroyed by Russia in the late 18th century. Its legacy would inspire future generations of Ukrainians, especially during periods of national revival. Lypynskyi supported the legitimacy of Pavlo Skoropadskyi, a direct descendant of Hetman Ivan Skoropadskyi (1646-1722), to rule over Ukraine.

However, both Lypynskyi and Skoropadskyi, along with other prominent Ukrainian political and cultural figures from that period, would eventually find themselves spending their final years in exile.

Lypynskyi would resettle first in Vienna. It was not the city that he had known before — the “bloom of that majestic imperial epoch…had definitively (been) brought to an end” by World War I. The police would keep an eye on his meetings and movements, as well as those of other Ukrainians, given their sudden prominence in the city. Some Ukrainians also battled with paranoia, fearing that the Bolsheviks would hunt them down and murder them. As one poet notes: “In exile, days flow like tears.”

The political infighting between the members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia that carried on in exile, which Lypynskyi could not help but contribute to, would also lead to him becoming a bitter recluse. He was pronounced “a mentally and spiritually enfeebled incendiary, who was destroying his life’s work with his own hands,” even by those who were once considered his allies.

The company Lypynskyi kept during his lifetime points to his historical significance. And yet, for English readers who are unfamiliar with Ukrainian history, it might be difficult to truly appreciate some of the novel’s scenes, like his time in Kyiv with an aging Ivan Franko, one of the leading figures of Ukrainian literature. Lypynskyi’s first encounter with writer and political activist Dmytro Dontsov is also depicted in the novel — Dontsov would go on to become one of his primary ideological adversaries, deviating from the Marxist principles of his early years to champion a dark take on ethno-nationalism.

Meanwhile, the narrator’s struggle, though it takes place in modern-day Ukraine, where matters of independence and national identity have remained relevant, appears mostly internal. She’s not quite sure why she’s so unhappy, acknowledging that her parents have always been more or less supportive. Additionally, she has achieved success and recognition early on for her writing and has no problem attracting men — including those who are already married. From an outsider’s perspective, it seems like she has nowhere to go but up.

“Instead of nurturing my mind, I trained at suffering,” she confesses.

The lack of similarities between Lypynskyi — “a person of the glorious old epoch of empires” — and the narrator raises questions about their intertwined stories. The narrator herself acknowledges this disparity, declaring: “Our lives were too disparate to comfortably fit into a shared narrative, if not for my irrational stubbornness.” However, it takes some time to discern what a man engaged in the life-and-death business of state building has in common with a promising young woman who struggles to find happiness in the world.

“He was an intellectual, a philosopher active in politics, a poet with a place in history. I’m just a person who manipulates words and ideas, with no real profession; I can write, or I can remain silent,” she writes.

It’s the choice to either express one's thoughts or maintain their silence that could be the common thread linking the narrator’s story to Lypynskyi’s. “This book is about being a victim,” Maljartschuk said in a recent interview with NPR. “It's not normal to live like that. It's a big work before you understand that. It's a start to give up your victim role.”

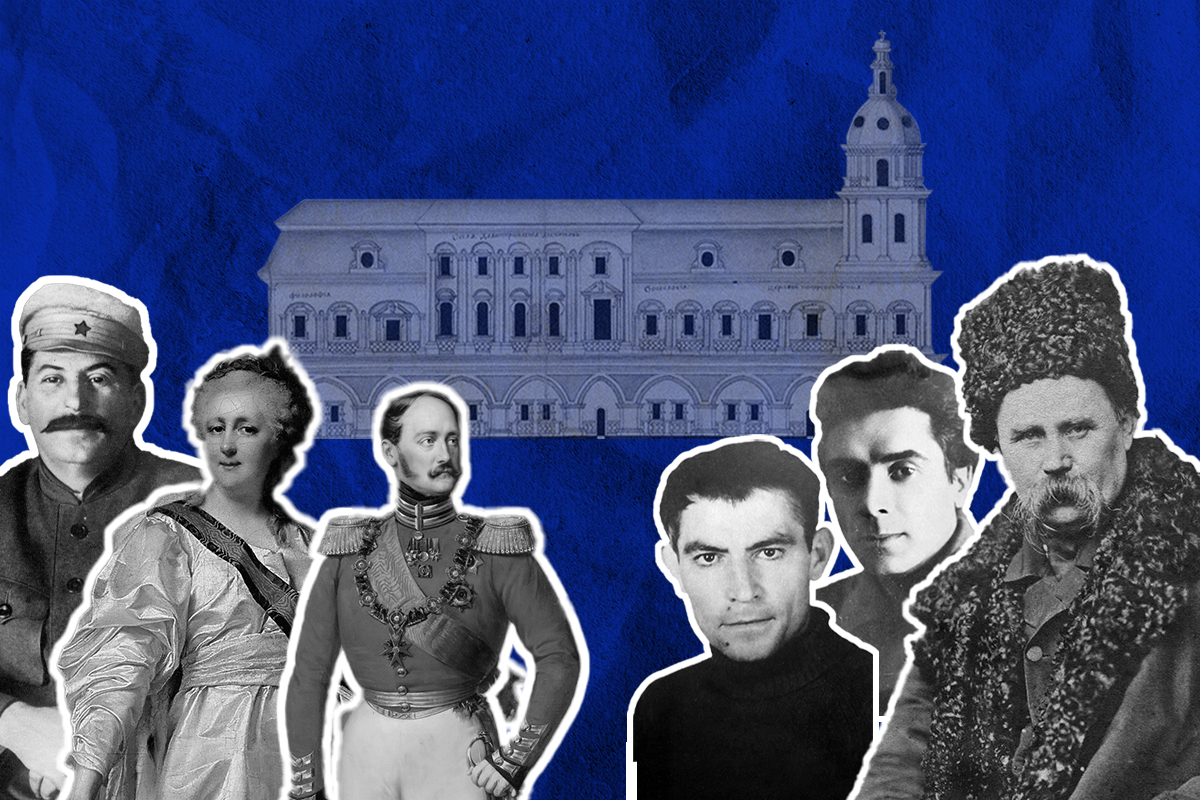

The reader eventually discovers that the narrator's resolute maternal grandmother, Sonia, lived through the Holodomor as a child. The Holodomor, an engineered famine, occurred between 1932 and 1933 under Joseph Stalin's rule, resulting in an estimated 3.5 to 5 million Ukrainian deaths — including Sonia’s mother. Her father left her on the steps of an orphanage, telling her that he would return with pampushky, though death would claim him, too.

When the narrator recalls her grandmother’s lessons on the art of how to mop a floor properly, a panic attack that later develops into agoraphobia manifests itself: “Time had stopped. The end had arrived and begun to stretch into eternity. I couldn’t breathe; I couldn’t scream. Grandma Sonia had screamed everything out before me. Her tragedy hung on to the living and refused to reach.”

The narrator’s Grandpa Bomchyk on her father’s side of the family, she also reveals, refused to become an insurgent alongside his neighbors against Soviet rule: “Till the end, he was convinced that he had done the right thing. Between a slavish existence and a heroic death, he chose the former.” Those who chose the path of insurgency would eventually be shot by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, their bodies displayed publicly as a warning to Ukrainians who harbored similar inclinations.

Given these dark chapters in her family history, the narrator calls herself “the offspring of meekness in the face of power and fear in the face of death.”

“And the price that had been paid to survive fell on my shoulders. Through the generations, considerable interest had accrued. Little by little, I had to start paying off my debts,” she adds.

Through these revelations, we come to realize that the narrator grapples with some form of inter-generational trauma. It's not a typical story of deciphering why she fails to appreciate all that life has given her. On a subconscious level, the narrator contends with the horrors endured by her family during Ukraine’s centuries-long fight to maintain its history, language, and culture. First published in Ukrainian by the Old Lion Publishing House in 2016, “Forgottenness” is part of a larger and ongoing trend in contemporary Ukrainian literature where authors are looking to the past in an effort to better understand the present.

In the novel's final pages, we find ourselves momentarily wondering whether it truly is inevitable that even the greatest and most noble achievements are susceptible to the relentlessness of time. But the novel ultimately underscores the importance that lies with those who, acknowledging this possibility, still confront the proverbial gigantic blue whale, steadfast in their resolve not to be relegated to oblivion.

Tanja Maljartschuk’s “Forgottenness” is now available to purchase in English translation from most major booksellers.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. Ukrainian culture has taken on an even more important meaning during wartime, so if you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.