30 years ago today, Ukraine traded nuclear arms for security assurances, a decision that still haunts Kyiv today

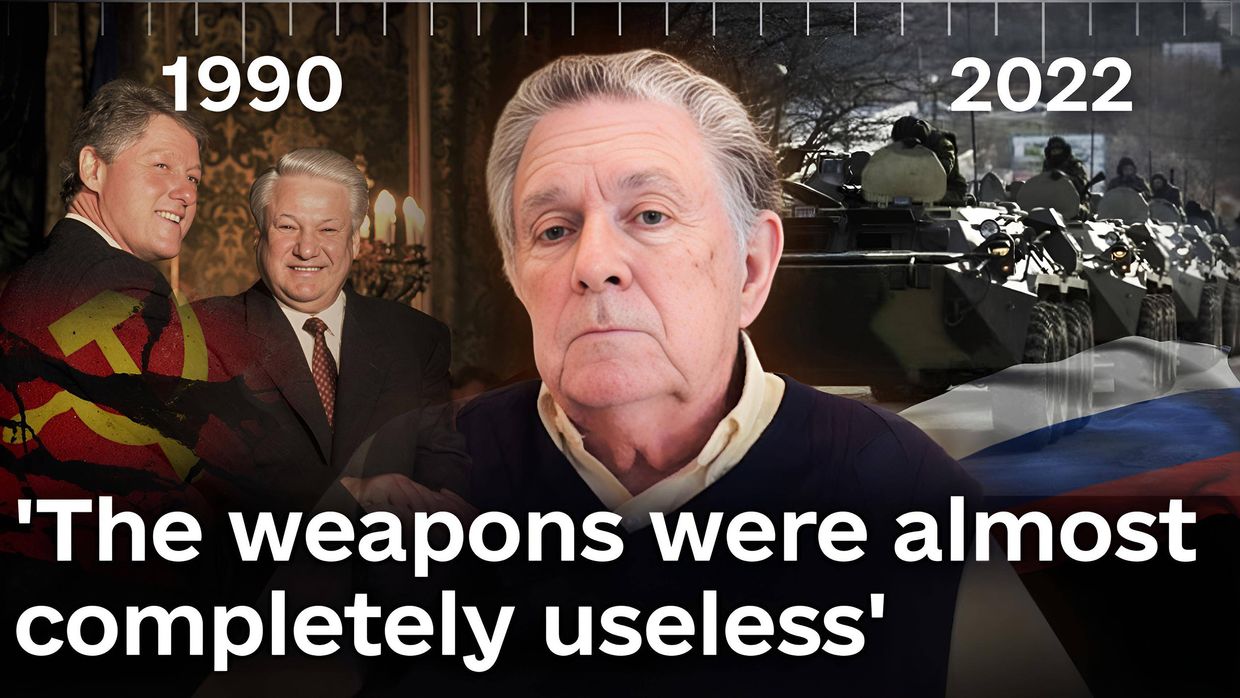

(L-R) U.S. President Bill Clinton, Russian President Boris Yeltsin, and Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk shaking hands after signing the historic Trilateral Agreement in Moscow, Russia on Jan. 14, 1994. (Diana Walker/Getty Images)

On Dec. 5, 1994, Ukraine had signed a set of political agreements that would guarantee the country's sovereignty and independence in return for accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

Signed in Budapest, the memorandum would lay grounds for Ukraine to dispose of its nuclear arsenal in return for the U.S., the U.K. and Russia to guarantee to not use economic and military means to attack the country.

Twenty years after signing the agreement, Russia launched a war against Ukraine, occupying Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine. Thirty years in, Russia is actively conducting a full-scale offensive against Ukraine, burning the cities and killing the people it once promised to protect.

The shadow of the events of 1994 haunts Ukraine today.

Despite the agreements, Ukraine did not receive the main benefit of giving up the world's third-largest nuclear potential — security. Many in Kyiv believe the country was pressured into an unequal agreement by the parties that had no intention to abide by what they had signed.

"Today, the Budapest Memorandum is a monument to short-sightedness in strategic security decision-making," Ukraine's Foreign Ministry's statement read ahead of the 30th anniversary of the agreement.

"It should serve as a reminder to the current leaders of the Euro-Atlantic community that building a European security architecture at the expense of Ukraine's interests, rather than taking them into consideration, is destined to failure."

How Ukraine lost everything

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was left with 176 intercontinental ballistic missiles, including 130 liquid-fueled SS-19 Stiletto and 46 solid-fueled SS-24 Scalpel, according to the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI). Ukraine also had between 1,514 and 2,156 strategic nuclear warheads and 2,800 to 4,200 tactical nuclear warheads in its arsenal.

Yet, Ukraine was not destined to keep its nuclear arsenal.

The provision on non-nuclear status was enshrined in the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine, adopted by the Ukrainian parliament on July 16, 1990. The provisions on the future nuclear status were also confirmed when Ukraine gained independence in 1991.

Within less than a year, Leonid Kravchuk, the first president of independent Ukraine, approved the Lisbon Protocol. The protocol supplemented the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) signed between the Soviet Union and the U.S. in 1984. The U.S., Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan also became signatories to the protocol.

According to the Lisbon Protocol, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan pledged to join the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), thereby renouncing their nuclear status.

On Dec. 5, 1994, Ukraine signed the Budapest Memorandum. According to the document, the signatory countries — the U.K., Russia, and the U.S. — pledged to be guarantors of Ukraine's independence, as well as sovereignty, and refrained from using weapons or economic pressure against Ukraine. In exchange, Ukraine renounced its nuclear status.

Anton Liagusha, the academic director of the master's program in Memory Studies and Public History at the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), says that Ukraine agreed to a non-nuclear status under enormous pressure.

"Russia used the Budapest Memorandum very cunningly. To be more precise, it encouraged and coerced the West to pressure Ukraine to sign the memorandum. At the same time, Russia positioned it as 'a noble act of global geopolitics,'" Liagusha said.

"Russia promoted the narrative that Ukraine is a failed state, a non-existent state, and non-existent means uncontrolled. And in a non-existent uncontrolled state, nuclear weapons are the worst possible option. Unfortunately, this cunning and sneaky diplomacy and propaganda reached their goals."

"Russia promoted the narrative that Ukraine is a failed state, a non-existent state, and non-existent means uncontrolled."

Ukraine entirely fulfilled its agreements in 1996: all nuclear warheads were transferred to Russia for destruction, and classified strategic bases were converted to non-military use. The guarantors, on the other hand, did not fulfill their obligations.

The historian described this step as a mistake because he firmly believes that today, nuclear weapons are still a guarantee of non-aggression and a certain guarantee of protecting one's sovereignty.

"At the time of signing the Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine was not able to ensure its sovereignty in the event of direct military aggression by Russia or some other states," Liagusha told the Kyiv Independent.

"This means that giving up nuclear weapons is a ridiculous story. And I am sure the politicians who signed this memorandum understood this."

Other experts interviewed by the Kyiv Independent noted that disarmament had some positive aspects.

Ukraine did not have access to the launch codes, but Russia did. Therefore, Ukraine could only store the weapons and not use them, but the storage also required a lot of resources.

"You need to keep constant security personnel at the sites, make sure that the warheads and missiles remain stable, and that there are no issues with them," Fabian Hoffmann, a defense expert and doctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Ukraine would have paid substantial amounts for something it cannot use. So, it would not have been very smart (to keep the weapons)."

According to Hoffman, Ukraine also risked becoming an international pariah like Iran or North Korea if it kept its nuclear warheads. Liviu Horovitz, a nuclear deterrence specialist at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, shared the same opinion.

"Everybody wanted Ukraine to give up those nuclear weapons, including the U.S. and all Western European powers. And hence, Ukraine basically would have had to take this decision against everybody else's will," Horovitz told the Kyiv Independent.

In exchange for giving up nuclear weapons, Ukraine also received economic benefits in the form of fuel for nuclear power plants. In the early 1990s, Ukraine was experiencing a financial crisis, and rolling blackouts were occurring nationwide. Thus, by giving up strategic bombers, Ukraine partially paid off its gas debts.

However, Horovitz agreed with Liagusha, saying that in the event of a full-scale invasion, nuclear weapons could help Ukraine in its defense against Russia.

"It is not like you acquire one lonely nuclear weapon, and suddenly, all foreign threats vanish. But historically, nuclear powers have better deterred their adversaries. Given Ukraine's conflict with the Russian Federation, probably it would not have been a bad idea, from a Ukrainian perspective, to own a nuclear arsenal," Horovitz said.

However, both Horovitz and Hoffman said that they do not see any short-term solutions for Ukraine, adding that the Ukrainian nuclear arsenal is the story of the past with no prospects in the future.

Stay warm with Ukrainian traditions this winter. Shop our seasonal merch collection.

Ghost of Budapest Memorandum

This fall, President Volodymyr Zelensky stirred up a new wave of discussions around the memorandum and the fulfillment of its terms.

"Either Ukraine will have nuclear weapons, which will serve as protection, or it must be part of some kind of alliance. Apart from NATO, we do not know of such an effective alliance," he said in October.

"Either Ukraine will have nuclear weapons, which will serve as protection, or it must be part of some kind of alliance."

Following the statement, Zelensky had to justify himself amid growing concerns of partners and ensure that Kyiv had no plans to develop new nuclear weapons but expected to join the alliance in the future. Yet, he once again highlighted the numerous violations of the Budapest Memorandum.

"This means it is not a good 'umbrella' for our security. That is why I said that I have no alternative but NATO. It was my signal."

Liagusha echoed Zelensky's stance, saying that the Budapest Memorandum turned out to be completely "empty," as there was no actual mechanism to protect Ukraine.

The Ukrainian historian argued that Ukraine should now invest in the development of nuclear weapons, while Hoffman and Horovitz remained more skeptical about this idea.

Ukraine does not have costly energy infrastructure that would be able to handle plutonium separation or uranium enrichment, the processes used to make nuclear weapons, Hoffman said. According to the expert, it can take "months, if not years," to construct the necessary facilities.

Ukraine will also not be able to do this quietly, as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) conducts so-called nuclear accounting, tracking all nuclear material inside any country with a nuclear power program.

"Because it could not be kept secret, you would have all those political drawbacks. This would not be very welcome abroad," Hoffman said.

"Russia would have every incentive to preempt a Ukrainian nuclear weapon… If Ukraine takes this further, there might be a nuclear preemption. But it would also be dangerous from a military perspective."

Liagusha, on the other hand, saw no reason to be cautious about Ukraine's potential development of new nuclear weapons. In the historian's view, there is no point in fearing an escalation of the war at this stage.

"We are in a situation of war and social catastrophe when we have little to lose but our own lives," Liagusha said.

"And Europe is as weak as it has ever been."