One critical shortage keeps Ukraine’s interceptor drones from blocking out Russia’s Shaheds

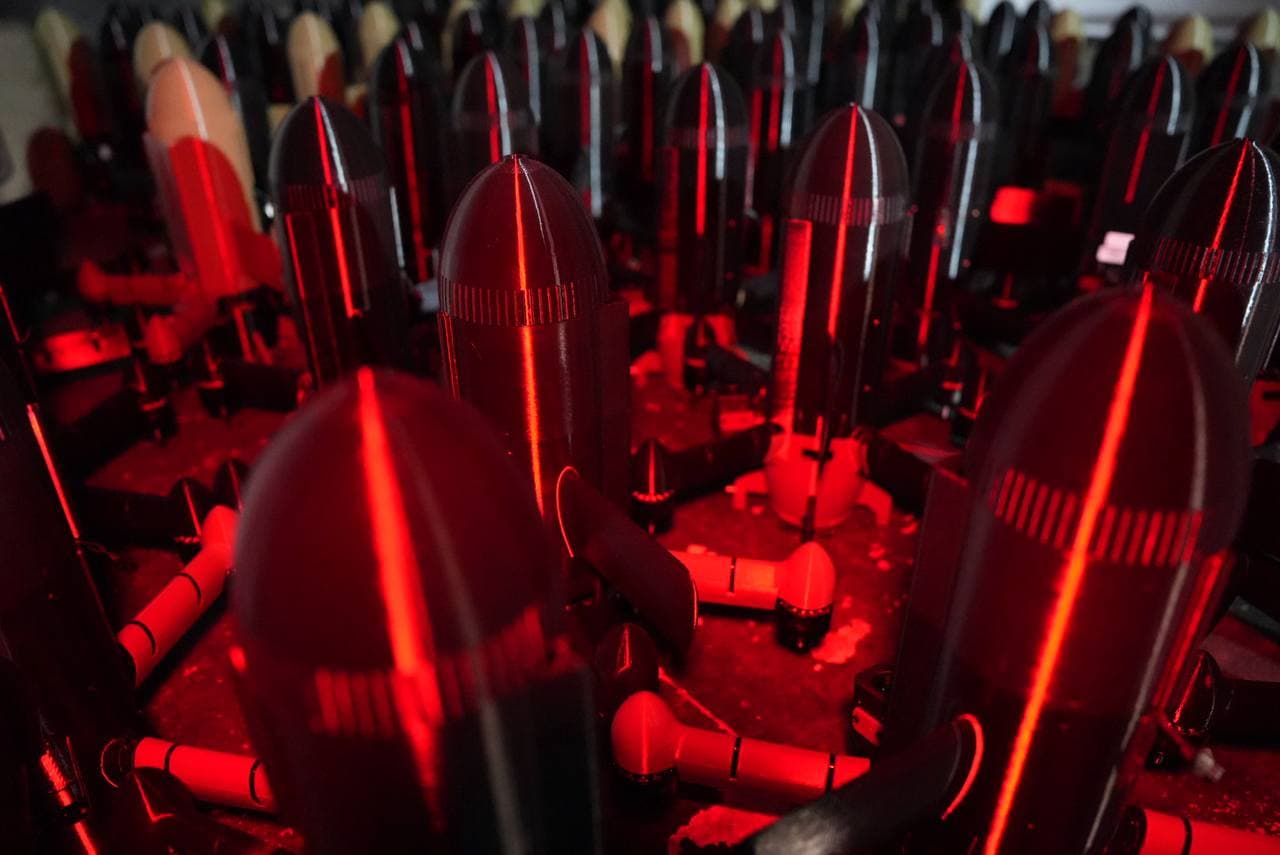

Sting drone interceptors in an undated photo. (Wild Hornets/Telegram)

October is coming to an end and as winter approaches, many Ukrainians find themselves more vulnerable than ever in the face of mounting Russian air attacks.

In Kyiv, Russian combined missile and drone attacks routinely result in mass casualty events. Smaller-scale drone attacks which occur on a near-nightly basis have until recently posed much less of a threat.

But overnight on Oct. 26, three people were killed and 32 others — including three children — were injured when two multi-story residential buildings in the capital were hit by drones during a relatively small Russian attack.

The tragedy highlighted a concerning pattern — an increasing proportion of Russian drones have been making it through Ukrainian air defenses to their targets.

To combat Russia's attack drones, Ukraine is putting a significant number of its air defense eggs in the basket of domestically-produced interceptor drones — first-person view (FPV) drones guided by a pilot that hunt enemy drones, either exploding next to them, or crashing into them.

Interceptor drones aren’t fast or hefty enough to protect against missiles, but since early this summer, they have been shooting down much slower moving Russian Shahed-type attack drones.

In July, Zelensky set a goal of producing some 1,000 per day. By the beginning of October, Oleksandr Syrskyi, commander-in-chief of Ukraine’s Armed Forces, said they were responsible for the majority of interceptions of Shahed-type attack drones.

"In November, we will get to 500-800 interceptors per day," President Volodymyr Zelensky told reporters in Kyiv on Oct. 27.

There are currently serious issues — cloudy autumn weather has seriously dampened Ukraine’s line-of-sight air defenses.

But more crucially, Ukraine has not managed to integrate the drones produced into a comprehensive air defense system. It’s not that hard to build 500-800 interceptor drones per day — deploying them is a different matter.

"If only they helped," Yuriy Kasianov, a former leader of a deep-strike drone team that was disbanded in October, told the Kyiv Independent.

"It’s impossible to build an effective defense against Shaheds with the help of interceptor drones, since for every drone you need an experienced operator, team, radar station — all of this takes tremendous infrastructure, a lot of funding, and huge dependence on the human factor."

It's an issue that Zelensky also acknowledged on Oct. 27, saying "we need to prepare operators," adding the process was "complicated."

Despite long-held hopes to build a better AI interceptor that will find and strike drones unaided, today’s interceptors remain more or less fully manual, dependent on a new generation of talented remote dog fighters.

One of them is call-signed "Ottoman."

"For everything you need time," Ottoman told the Kyiv Independent from an interceptor workshop near Izium near the northeastern border with Russia.

"(Russians) start using a new tactic and can, in the time that we’re adapting to it, build up a bunch of variations."

Ottoman flies for the 3rd Army Corps’ anti-drone unit, Squadron. With around 60 Shahed-type drones shot down and, his comrades estimate, 200 other Russian drones intercepted, the 21-year-old Ottoman may be the best anti-drone drone pilot in the world.

His secret? "No secret, I just feel it."

The 3rd Army Corps — until recently known as the 3rd Assault Brigade — is a highly independent and famously efficient unit within Ukraine’s war effort.

Part of the reason they ended up with interceptors is simply that they have the money and infrastructure for good kit, a trait not evenly distributed across units.

The 3rd’s anti-air defense, while it keeps attack drones from making it through to civilian cities, is tasked first and foremost with defending military positions in Kharkiv Oblast.

Ottoman still regularly sits at a position east of Izium waiting for drones to cross his team’s radar screens, but the Ukrainian military also shuttles the apple-cheeked dog fighter around the country in an attempt to share his learning with the rest of their air defense.

That education has not made it uniformly across the country.

Oleksiy is a deputy commander responsible for coordinating four air defense units guarding the north side of Kyiv.

"We have only one unit training," Oleksiy, who asked not to be identified by last name out of security concerns, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Adjuncts are also at the development stage of units. The approximate timeframe when they will be ready to fulfil military missions is the end of this year."

For civilians across Ukraine, time is ticking.