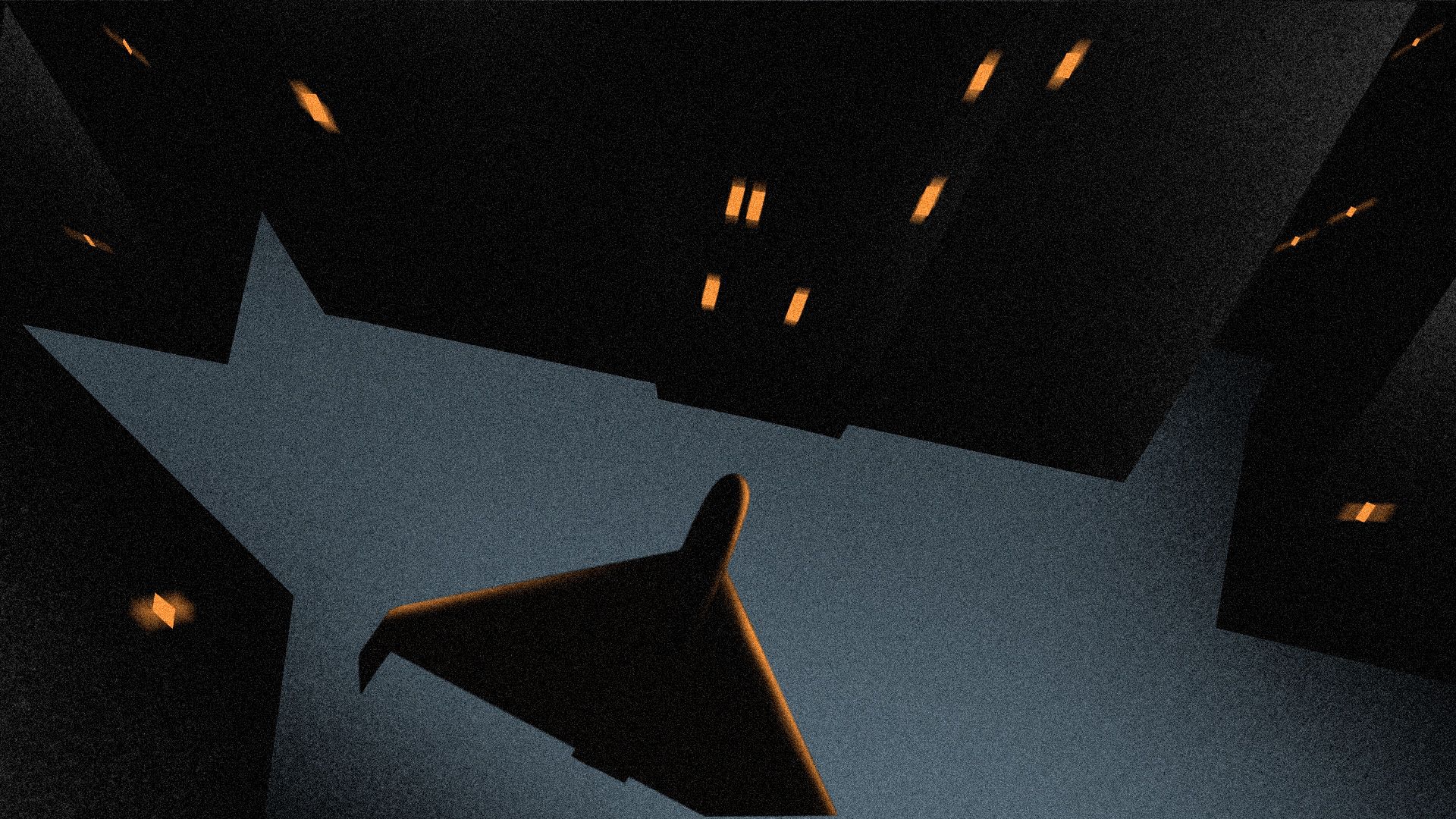

Winter has grounded Ukraine's interceptor drones, gutting Kyiv's air defense

Employees repair sections of heat and power plant damaged by Russian air strikes in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Feb. 4, 2026. (Roman Pilipey / AFP via Getty Images)

From his base near the hotly contested town of Kostiantynivka, Donetsk Oblast, Vladyslav has, by his own estimates, downed upwards of 60 Russian drones using Ukrainian interceptor drones over the past year.

Winter has exposed many foundational frailties in Ukraine's air defenses. Relentless Russian attacks utilising Shahed-type attack drones have left millions of Ukrainians in the dark and cold. The role of interceptor pilots like Vladyslav is more important than ever.

Interceptor drones are first-person view (FPV) drones guided by a pilot that hunt enemy drones, either exploding next to them, or crashing into them.

Yet, despite massive Ukrainian and foreign investment into such interceptors, which promised to take the place of dwindling stockpiles of anti-air missiles, Vladyslav's job keeps getting harder.

The first tip he has for any new pilot: Don't work against the wind.

"For example, say your target is 10 kilometers away. There’s a headwind of 40 kilometers an hour at 500 meters. I would keep as low as possible until the moment I want to take on altitude — say two kilometers from the target — and I’ll have gone through eight on minimum speed, with minimal gas, and then I go up gradually, not fast," Vladyslav, who per Ukrainian military protocols asked not to be identified by last name, told the Kyiv Independent.

read also

The interplay between the weather and the limits of drone frames, cameras, motors, and batteries becomes much more complicated in the winter chill. Lithium-ion and lithium-polymer batteries alike are notoriously finicky at lower temperatures, especially the -20° Celsius (-4 degrees Fahrenheit) lows that Ukraine has seen in recent months for the first time since Russia's full-scale invasion.

”Before a flight we try to keep our drones in the heat. When we’re flying, we set them out and take off immediately. You don’t want to gun it until the battery has a chance to heat up," Vladyslav continues.

Oleksiy, who coordinates territorial defense of mobile air groups north of Kyiv, agrees. "The cold affects the duration of work of the devices. Naturally if temperatures were positive, it would be much better," he told the Kyiv Independent.

Beyond the cold itself, the fog, low cloud cover, and frequent precipitation all complicate drone air defense.

"An interceptor drone was an effective device in good meteorological conditions — not in -20°, not in snow, not in rain. This merits attention," Anatolii Khrapchynsky, an aviation expert and reservist in the Ukrainian Air Force, told the Kyiv Independent.

Despite optimistic predictions of expanded production numbers, faster motors and greater autonomy, Ukrainian interceptor pilots are left economizing limited supplies of the drones they need. Meanwhile the Russian drones they hunt have gotten much better at escaping and dodging them.

"Before, (Russian drones) might circle the same place for an hour or two. Now they fly in, do a loop and, at the same speed, fly off," Vladyslav said of the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) drones he often encounters at the front line. "In our sector they’ve gotten more autonomous and they’ve added automated dodging."

Ukraine’s interceptors are by and large powered by lithium-ion or lithium-polymer batteries and guided via active links with their pilots. Russia’s Shahed-type attack drones and their various locally made knock-offs are powered by either two-stroke or jet engines, both of which generate their own heat. They also spend more flight time high above cloud cover and have more automated guidance than the interceptors looking for them.

Weather also keeps many Russian drone models grounded, but Russia has the advantage of making traditional air defense missiles domestically at likely the largest scale in the world. The differential between Russian air power and Ukrainian air defenses has left Ukrainian cities more vulnerable than ever, including Kyiv, the epicenter of an ongoing energy crisis.

"If you as a commander are constantly dependent on one thing, and then that one thing fails, that is a catastrophic problem," Jorge Rivero, a former explosive specialist with the U.S. marines and now Russia researcher for the Institute for Defense Analysis, told the Kyiv Independent.

"In 1917, during the Great War, we said, ‘hey, our entire battle plan revolves around artillery,’ and then it started raining and artillery couldn’t fire anymore. That was a huge problem. Basically, we're doing the exact same thing with these drones."

Gaps in civil defense

Ukraine’s air defense unfortunately is most essential during the cold, when Russia goes out of its way to shut down power plants and heating facilities.

Even outside of mass air attacks, there have been some conspicuous failures. On Jan. 26 the distinctive rumble of a Shahed engine echoed out over Kyiv well before the siren of any air alert. The lone drone had somehow managed to evade detection in the 1,000 kilometers from the Russian border.

In a Feb. 11 statement to the Kyiv Independent, Ukraine’s General Staff wrote that answering questions about interceptor effectiveness could "negatively affect the progress of the assigned tasks during the legal regime of martial law."

"In conditions of difficult weather, the main and most effective means remain SAM missiles, which are all-weather."

The lack of air defense has, however, been painfully obvious. Over the winter, many Ukrainian figures including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky publicly touted the need for more ammunition donations for Western systems like Patriots, SAMP/Ts and NASAMs.

Zelensky said on Feb. 12 that "acceleration is needed with packages for our air defense. This is the key task right now not only for Ukraine, but for everyone in Europe. The Russians must not get used to the idea that their missiles and 'Shaheds' are helping them in any way."

Only recently have Ukrainian officials acknowledged even obliquely that interceptor drones have not lived up to their promise to fill in the gaps in traditional air defense.

"In conditions of difficult weather, the main and most effective means remain SAM missiles, which are all-weather. In favorable weather conditions, aviation, helicopters and drone interceptors are involved," Commander-in-Chief of Ukraine’s Armed Forces Oleksandr Syrsky wrote on Feb. 12, promising however that, "the quantity and quality of interceptor-drones is growing."

The acknowledgement is especially bitter given the enthusiasm with which Ukraine has touted its domestic interceptor drones over the past year.

Forecasts of technological and industrial leaps forward including Zelensky's prediction of 1,000 per day last July have not manifested in safer Ukrainian airspace.

Also on Feb. 12, newly appointed Defense Minister Mykhaylo Fedorov wrote on X that "sky protection is priority #1. We are launching a multi-layered ‘small’ air defense system and new interceptors to counter long-range drones. Organizational and leadership changes have been made to ensure our cities remain safe from 'Shaheds.'"

Khrapchynsky summarized his proscribed changes to air defense: "We need to expand to the maximum production of interceptor missiles, create cheaper devices for interception, and correspondingly increase the number of devices for tactical radiolocation."

Assessing production of all of Ukraine's weaponry remains a difficult endeavor due to military secrecy as well as conflicting reports.

While still defense minister just a month ago, Fedorov's predecessor Denys Shmyhal, claimed that the ministry was already delivering 1,500 interceptors per day to soldiers. In the month that followed, Russian attacks knocked out heating for the rest of the season for many Kyivans. Shmyhal, previously the prime minister, moved over to the Energy Ministry, replacing a former colleague recently arrested for what authorities call a massive corruption scheme that gutted Ukraine's energy defenses.

"Honestly, we haven’t seen any changes yet," Vladyslav told the Kyiv Independent on Feb. 13. His unit, he says, doesn’t get enough Sting drones, and those that they receive still have no last-mile targeting.

Neither the Defense Ministry nor the Office of the President returned requests for comment.

Asami Terajima contributed reporting to this article.