Where is Ukraine's Donbas? 6 things to know about the region Russia wants to take

Ukrainian soldiers near Donetsk Oblast entrance sign, protected by anti-drone netting and surrounded by Ukrainian brigade flags, on Feb. 2, 2025. (Roman Pilipey / AFP via Getty Images)

Russian President Vladimir Putin has drawn a stark new line in the war: Ukraine must withdraw its forces from the eastern Donbas region, or Moscow will seize it "by force," he warned on Dec. 4.

The threat is hardly new — but the stakes are. President Volodymyr Zelensky has ruled out ceding territory.

After a decade of trying and failing to take Donbas outright, the Kremlin is now tying any future ceasefire to Ukraine's capitulation on the region, raising the pressure as Moscow seeks to reshape the war's endgame on its own terms.

So what is Donbas? And why is Russia so obsessed with it?

Where is Donbas?

Donbas is a historical region in eastern Ukraine. The term "Donbas" is short for "Donets Coal Basin," named after the Siverskyi Donets River that runs through the region.

The word has been in use since the 19th century and has referred not only to modern Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts but also parts of Ukraine's Dnipropetrovsk Oblast and even regions of southern Russia, where the Siverskyi Donets River also flows.

The region is best known as Ukraine's industrial and coal-mining heartland — a symbol of the country's heavy industry. Yet parts of Donbas are also agricultural, with sprawling farmlands surrounding its industrial centers.

Donetsk and Luhansk, the two oblasts that make up the core of Donbas, have long been economic powerhouses built on coal, steel, and machinery.

Russia's war began in Donbas

Russia's war against Ukraine started not in 2022 but in 2014 — with the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Donbas. That's why Ukrainians often refer to 2022 as the start of the full-scale phase of a war that had already been raging for years.

From the beginning, Moscow tried to disguise its aggression.

While boasting about the annexation of Crimea, it denied involvement in its war in Donbas, promoting a false narrative that allegedly local "separatists" were responsible for the fighting.

In reality, there was no genuine separatist movement. The proxy republics were Kremlin creations — armed, funded, and directed from Moscow as part of a broader campaign to destabilize Ukraine.

Ukraine's economic powerhouse

For much of Ukraine's modern history, Donbas was its economic engine.

Before Russia's invasion, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts were home to hundreds of metallurgical, coal, and chemical plants that exported globally.

According to the London-based Center for Economics and Business Research, the region accounted for roughly 15.7% of Ukraine's GDP and 14.7% of its population before 2014.

Russia's war changed everything. The work of many of these enterprises came to a standstill as Russian attacks damaged industrial property, millions of locals fled the hostilities, and blockades between Ukraine and Russian-occupied territories abolished trade.

The invasion also led to a fall in Ukraine's international exports and foreign investment.

Between 2014 and 2021, the same research center estimated Ukraine lost $102 billion due to the war in Donbas — about 8% of its pre-war GDP each year.

Still, many businesses continued to operate, in spite of a front line that moved closer after 2022.

Earlier this year, however, a critical Donbas coal mine was forced to close due Russia's advances in the area. It was Ukraine's last operating coking coal mine, dealing a blow to Ukraine's economy.

Donbas is people, not just territory

The war's human cost has been immense.

Between 2014 and December 2021, at least 3,400 civilians and 4,400 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in Donbas, according to U.N. data. Nearly 20,000 were injured.

At least two million people were forced to flee their homes because of the fighting. Roughly the same amount of people continued to live under Russian occupation — amid poverty, Kremlin indoctrination, and crossfire along the front, as Ukraine fought off continuous Russian attacks.

Since 2022, Russia has destroyed many cities and villages in the region. In Mariupol alone, which was home to about 500,000 people before Moscow's full-scale invasion, estimates suggest that Russia has killed up to 75,000 civilians.

The actual cost of Russia’s war, beyond the numbers, is yet to be fully grasped.

"When you talk about Donetsk Oblast like a hot cake that can be passed around," Oleksii Ladyka, a local journalist from Kramatorsk now serving with Ukraine's 92nd Assault Brigade, told the Kyiv Independent in August.

"I want them to remember that everyone here has their own family, has their loved ones, has a hope and a wish for a peaceful life and a future for their children, just like anyone anywhere in the world."

Russian-speaking region

One of Moscow's oldest myths is that Donbas "naturally" belongs to Russia because many of its residents speak Russian. In reality, language has never equaled nationality or political leaning.

Before 2014, the vast majority of Donetsk and Luhansk residents identified as Ukrainian citizens. Polls consistently showed that most wanted to remain part of Ukraine.

Russia has long exploited linguistic ties to justify its aggression — but speaking Russian does not mean supporting Moscow.

A poll conducted by the Kyiv-based think tank Razumkov Center between April 24 and May 4, 2025, found that 82% of Ukraine’s Russian-speaking population expressed a negative view of Russia.

Russia's claims of "saving" Russian-speaking Ukrainians do not add up in the face of widespread destruction. Years of neglect and war damage have also left Russian-occupied areas of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts with barely functioning infrastructure, leading to a water crisis in these regions in the summer of 2025.

Donbas as a military fortress

The true reason behind Putin's interest in gaining Donbas is likely military in nature.

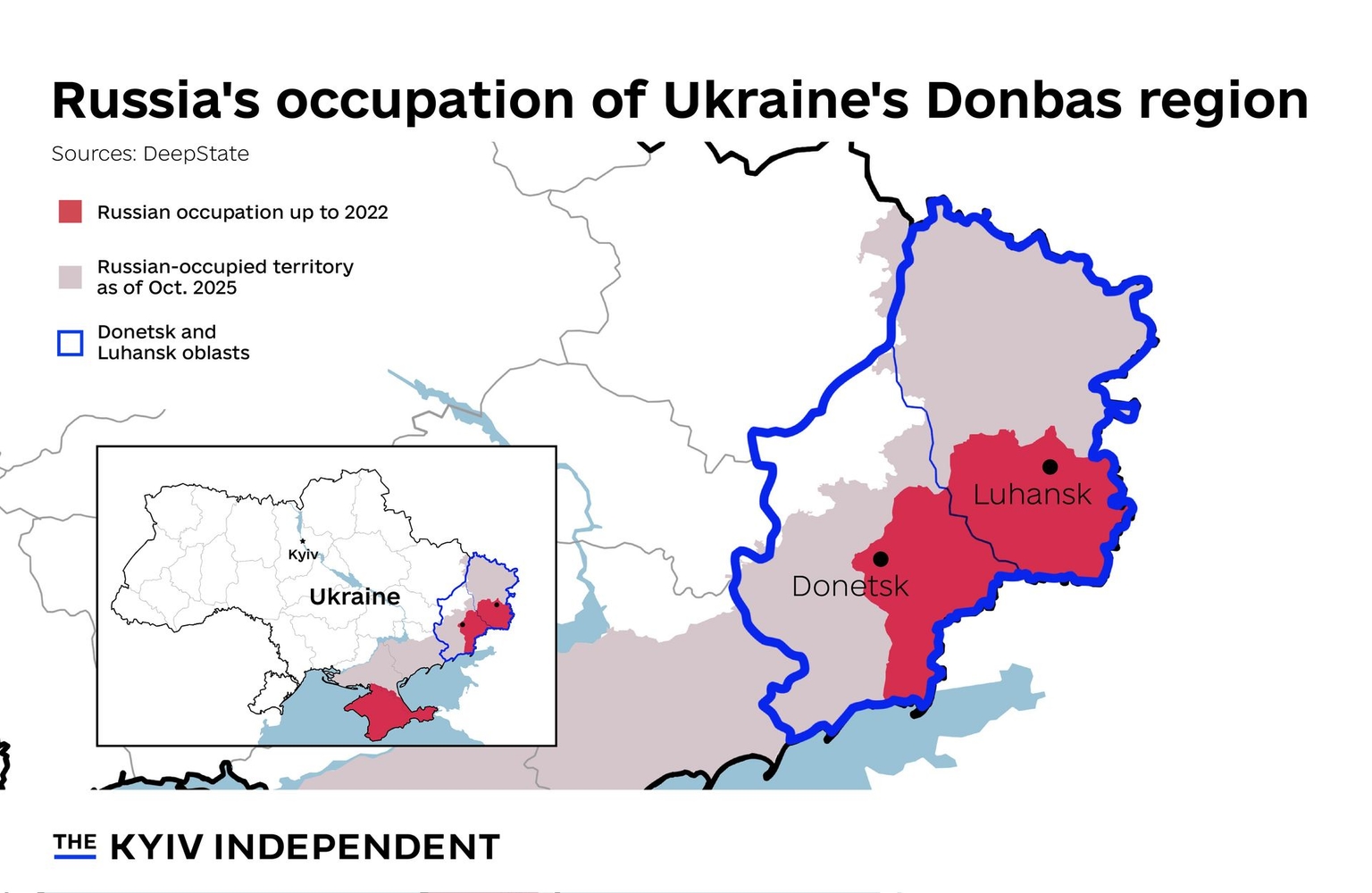

By mid-August 2025, Russia had occupied 19% of Ukraine's territory, according to Reuters.

Luhansk Oblast is almost entirely under Russian control, while Ukrainian forces continue to hold firm in parts of Donetsk Oblast — roughly 6,600 square kilometers (2,550 square miles), including the key cities of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, with the battle for Pokrovsk still continuing.

For Putin, full control over Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast remains a top demand.

As the Economist put it, the real reason lies in Ukraine's so-called "fortress belt" — a 50-kilometer (31-mile) stretch of heavily fortified towns from Sloviansk and Kramatorsk to Druzhkivka and Kostiantynivka.

This network of fortifications, trenches, minefields, and anti-tank barriers has been continuously strengthened since 2014. After Bakhmut was occupied in 2023, Ukraine redoubled its efforts to reinforce the line.

Former Defense Minister Andriy Zagorodnyuk told the Economist that enormous resources had been poured into the defense network, turning Sloviansk and Kramatorsk into "fortress cities" — logistical hubs and industrial strongholds that have so far resisted Russia's advance.

The situation in Donbas now

The latest U.S.-backed 28-point peace plan — drafted by U.S. Special Envoy Steve Witkoff together with Kirill Dmitriev, the head of Russia's sovereign wealth fund — envisions Ukraine withdrawing its forces from the region entirely.

Putin reiterated on Nov. 27 that a pullback of Ukrainian troops is his key condition for any ceasefire, even as Washington attempts to revive stalled negotiations.

For Kyiv, the idea of "swapping" the parts of Donbas still under control remains unthinkable.

It would mean surrendering the very territory Moscow has failed to seize since the very beginning of its invasion in 2014.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Tim. Thanks so much for reading! At the Kyiv Independent, we don't have a wealthy owner or a paywall — we rely on readers like you to keep our journalism alive. Our goal is to explain the world clearly and walk you through what's really happening, so you can understand the events shaping Ukraine and beyond. If you found this article helpful, consider joining our community today and supporting independent reporting.