Who does Crimea really belong to?

Russia's war against Ukraine began in Crimea.

In February 2014, as the pro-Russian regime in Kyiv was killing protesters on the barricades of the EuroMaidan Revolution, thousands of Russian troops without insignia began occupying strategic locations and military bases in the Crimean Peninsula.

Within a month, Russia had illegally annexed Crimea on the back of a sham referendum at gunpoint, and unrest led by Russian-led militants had begun in eastern Ukraine.

The fact that Russia decided to launch its war against Ukraine in Crimea isn't surprising.

Crimea has long been a cornerstone of the Russian imperial narrative, with the country's centuries-long propaganda placing Russia as the "rightful historical owner" of the Ukrainian peninsula.

The annexation of Ukrainian territory was widely supported by those living in Russia, with Russian President Vladimir Putin's approval ratings skyrocketing to over 80% in the months after the start of the war.

Basic principles of territorial sovereignty and a rules-based international order make a strong case for Crimea to remain an inseparable part of Ukraine.

However, since annexation, Russian propaganda has successfully spread the narrative of Russia's "return" of a "historic Russian land" among the international public, with many Western leaders soon abstaining from asserting that Ukraine must get the peninsula back.

This chapter of Ukraine's True History will explore the historical context that led to Crimea as it is today and answer why Russia doesn't have a "historic right" to annex Ukrainian Crimea.

From diversity to ethnogenesis

With its prime geographic position on the Black Sea, the crossroads between the Eurasian steppe, and the Mediterranean trading routes, the Crimean Peninsula has been inhabited by dozens of ethnic groups over its long history.

Several of Crimea's major cities today, including coastal cities Feodosia and Kerch, have origins in ancient Greek colonies established on the coast of the peninsula from the 7th-5th centuries BCE, eventually joining together as the Cimmerian Bosporan Kingdom, which would go on to become a client state of the Roman Empire.

Meanwhile, the interior of Crimea was populated by the nomadic Scythians, which resided in the vast steppes of what is now southern Ukraine and Russia.

Over the centuries, the peninsula would be occupied by many nomadic people who passed through the area, including the Goths, Cumans, Huns, and Khazars, and was later contested between the Byzantine Empire and the Grand Princes of Rus in Kyiv.

In the same cataclysm that brought about the fall of Kyivan Rus, the Mongol invasion of Europe in the 13th century also swept through Crimea. For two centuries, the Mongol successor state known as the Golden Horde ruled most of the peninsula, while the coastal settlements were colonized by Genoese traders.

It was during this time that a new nation began to form in Crimea in a process known as ethnogenesis. Descendants of the many different nations that inhabited the peninsula began to congregate, united by the Muslim faith and a Turkic language similar to that spoken by the Cumans and the Khazars.

When the power of the Golden Horde in Europe disintegrated in the 15th century, this new indigenous people group, who came to be known as the Crimean Tatars, quickly established their own state.

Ruled by the House of Giray from its capital in Bakhchysarai, the Crimean Khanate would come to be a formidable force in Eastern Europe, dominating the steppes of southern Ukraine and leaving tangible cultural heritage sites across the Black Sea coast.

Imperial conquest

The history of the Crimean Tatar nation is woven tightly with the history of Ukrainian proto-states, as the trajectories of both were defined by their encounters with larger, more powerful outside empires competing for land and resources.

During this time, the Crimean Tatars both competed and cooperated with the emerging Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, a loose confederation of Ukrainian people that inhabited much of modern central and eastern Ukraine, conducting raids and military campaigns from their forts along the Dnipro River.

Although the Ukrainian Cossacks and the Crimean Tatars often fought on different sides, they also traded extensively and sometimes formed alliances, such as when Cossack leader Petro Doroshenko allied with both the Crimean Tatars and the Ottomans against Poland and later the Russian Empire in the mid-17th century.

Ultimately, both the Crimean Khanate and the Cossack Hetmanate were annexed into the Russian Empire around the same time, in the late 17th century, during the conquering reign of Russian Empress Catherine II.

With Ukraine's neighboring great powers, Poland and the Ottoman Empire, significantly weakened, the counterbalance that had kept Russian expansion at bay was no more.

It was with the arrival of Catherine's Russia in 1783 that the erasure of indigenous Crimean Tatar history began, hand-in-hand with the repression of its people.

Assuming an image of the restorer of Western civilization in the area, Catherine founded completely new cities along the Black Sea coast, often opting for anachronistic Greek-sounding names such as Sevastopol, Odesa, and Kherson.

It was then that these Crimean Tatar lands, together with much of southern and eastern Ukraine, were dubbed "Novorossiya" ("New Russia"), a term used prominently by Vladimir Putin and Kremlin propaganda to justify the conquest of parts of Ukraine since 2014.

According to American historian Brian Boeck, "grafting 'New Russia' onto the Russian Empire required re-imagining this space as Russian, and the consolidation of tsarist authority relied on settlement."

In the century after their annexation, the indigenous Crimean Tatar lands were subject to a policy of active colonization and demographic degradation.

With tens of thousands of Russian and Ukrainian settlers and serfs resettled to the peninsula, Crimean Tatars were expelled from their lands and homes and marginalized from the new ruling government and society built from scratch in the Russian imperial mold.

These processes accelerated greatly after the end of the Crimean War between the Russian Empire and the alliance of Ottoman, French, British, and Sardinian troops in 1856. The Crimean Tatars were uprooted by the war from their homelands in the interior, and many of them ultimately fled permanently to the Ottoman Empire.

In a Russian Empire census carried out in 1850, Crimean Tatars still made up the vast majority of Crimea's population at 77.8%, but by 1897, this figure was down to 35.5%.

Thus began the only historical period of brutal Russian rule in Crimea.

Erasing a nation

For both the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar nations, the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 allowed a brief window into which modern states could be founded.

In Crimea, this movement began with the first congress of Crimean Tatar Muslim leaders in March 1917.

In July, a new Crimean Tatar political party was formed, advocating for independence. By December, while the Bolshevik revolution was sweeping through Russia, the first sitting of a new Crimean Tatar parliament was held in Bakhchysarai, the old capital of the Crimean Khanate.

Known as the Qurultai according to the Turkic tradition, the body declared the formation of the Crimean People's Republic, complete with its own constitution and government structure.

Simultaneously, successive Ukrainian independence movements also exploited the power gap between Russia and Germany to found their own state projects, the most significant of which was the Ukrainian People's Republic.

With aligning goals of national self-determination and independence from the empire, the two fledging states recognized each other and held numerous negotiations during the early revolutionary period, with both sides open to further integration.

"The Ukrainians' federal approach and innovative emphasis on national minority rights could have led to closer cooperation, but a loose arrangement seemed fine," according to British historian and University College London professor Andrew Wilson, who authored a 2021 paper on the respective interpretations of Crimean Tatar history by Russia, Ukraine, and Crimean Tatars themselves.

Though control of Crimea changed hands several times during this time, ultimately, both the Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian states were once again swallowed by Russia, with the exception of parts of western Ukraine.

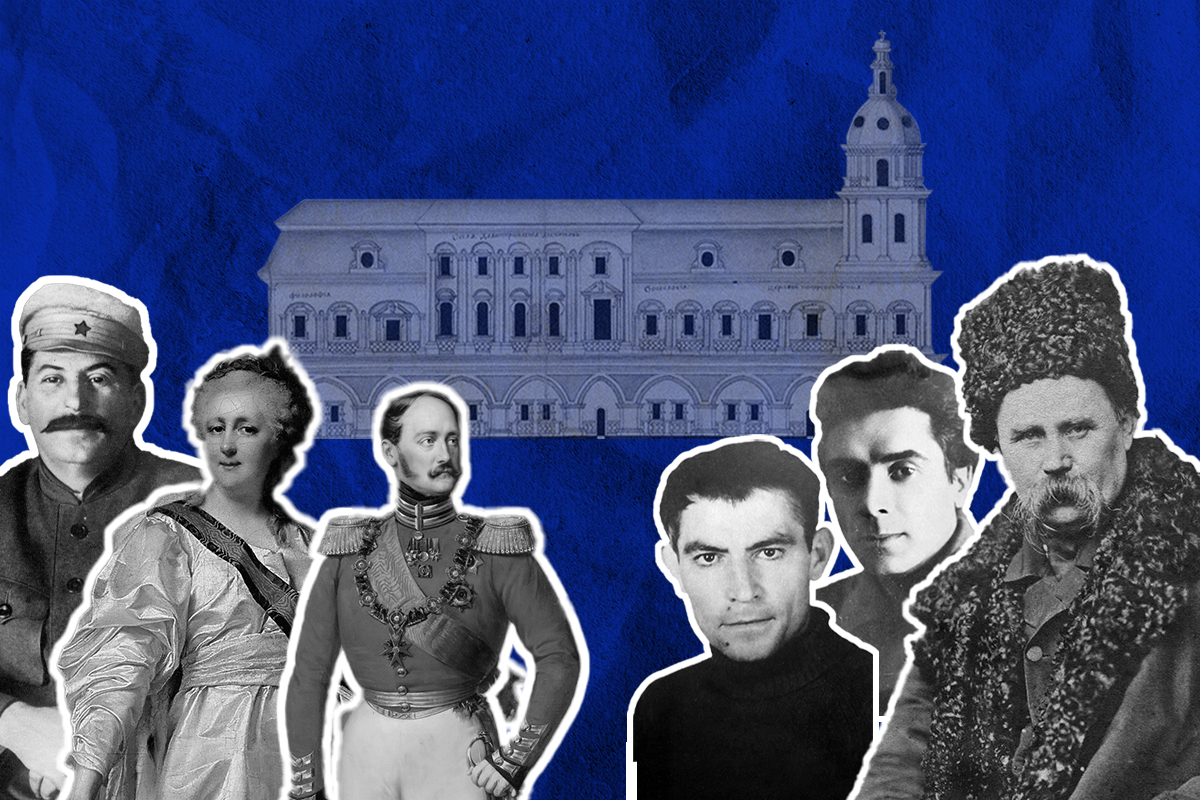

As with Ukraine, the early Soviet regime did give some support to Crimean Tatar culture and minority rights, but this was soon reversed under the Russification-driven policies of Joseph Stalin after he assumed full power in the late 1920s.

After years of famine and political repressions in the early Stalin era, by the outbreak of World War II, Crimean Tatars only consisted of 19.4% of the population, with almost half of the peninsula's 1.1 million residents by then being ethnically Russian.

Soon, in one of the most brutal episodes of ethnic cleansing of the war, the population of Crimean Tatars in Crimea was reduced to zero.

Soviet authorities, using contrived allegations of an entire people collaborating with Nazi Germany, forcibly deported the entire Crimean Tatar population of over 200,000 to Central Asia in 1944.

The collective trauma of the deportation and following decades, known to Crimean Tatars as Sürgünlik ("exile"), had a lasting impact on the people's attitudes toward Moscow.

Around 6,000 are understood to have died during the journey itself, and many tens of thousands more from the conditions in the settlements they were moved to, much akin to prison camps.

Estimates vary as to the exact figure, but even according to the estimates of the NKVD, Soviet Interior Ministry, 27% of the entire Crimean Tatar population died either from the deportation itself or from malnourishment, disease, or exposure in the years after arrival.

Upper historical estimates put the figure at closer to 46%.

From that point, Soviet historiography made a new concerted effort to minimize the Crimean Tatars' role in the history of the peninsula.

In this narrative, the indigenous status of Crimean Tatars was dismantled. Instead, the nation was depicted as only one in a series of conquering tribes that had settled in the area.

"The general line was now to fight against the 'idealization' of 'Tatar' history," says Wilson, "and assert that the Crimean lands, even in primordial times, belonged to the Slavs and the Russians and their ancestors, the Scythians."

In 1954, in a decision that has been decried as illegal by Russian propaganda narratives since 2014, Stalin's successor Nikita Khrushchev authorized the transfer of Crimea, including the naval city of Sevastopol, to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

This decision, formally marking the 300th anniversary of the 1654 Treaty of Pereiaslav between Ukrainian Cossacks and Russia, was also motivated by economic rationality and was enshrined in law both by the Supreme Soviet and in the constitutions of both the Ukrainian and Russian SSRs.

Crimea and independent Ukraine

The path of Crimea towards being part of an independent, democratic Ukraine begins a few years before the end of Soviet rule, with the return of the Crimean Tatar people from exile in Central Asia to their homelands.

After decades of activism in a harshly authoritarian environment, Crimean Tatars began to return in the late 1980s after over four decades of being displaced.

At the height of Soviet ruler Mikhail Gorbachev's liberalizing reforms, over 200,000 Crimean Tatars were able to return to the peninsula, but in most cases, they had no home to return to. The Crimean Tatar-owned land has long been expropriated by incoming Russian settlers, and many villages have completely been ruined and abandoned.

In late 1991, with the Soviet Union in its death throes, the Verkhovna Rada, which governed all of the Ukrainian SSR at the time with increasing independence from Moscow, declared Ukraine to be an independent sovereign state.

In a nationwide referendum conducted in December, Crimea voted in favor of Ukraine's declaration of independence, with 54% of Crimean voters supporting the move.

In a 1994 agreement known as the Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia committed to respect Ukraine's territorial integrity and sovereignty and refrain from using or threatening to use force against Ukraine.

In turn, Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal, the third-largest at that time.

The Budapest Memorandum commitments were violated together with the core principles of the United Nations Charter 20 years later.

Upon his election in 2010, Ukraine’s pro-Kremlin President Viktor Yanukovych signed the Kharkiv Pact, extending Russia's lease on the base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, Crimea, in exchange for gas discounts for Ukraine.

Russia has quartered its fleet in Sevastopol since Ukraine's independence, with the existing lease permitting Russian troops to be stationed in the city until 2017. The troops weren't permitted to leave the city without Kyiv's consent.

In the winter of 2013-2014, Yanukovych ordered the beating and shooting of protesters on Independence Square in Kyiv in what became known as the EuroMaidan Revolution.

Meanwhile, there were also pro-Ukrainian protests in Crimea, particularly in the capital city of Simferopol, where the Crimean Tatar community played a large role. These pro-EuroMaidan protests were often met with counter-demonstrations by pro-Russian groups, resulting in tensions and occasional violence.

History repeats itself

When Russian troops illegally occupied Crimea just a week after the end of the EuroMaidan Revolution, Russian propaganda began attempting to justify the war.

In a sham referendum in March 2014 that would come to be repeated in four more regions of Ukraine in 2022, Moscow reported 97% of the population in Crimea requested to join Russia.

The sham vote was condemned and declared invalid by the UN General Assembly later that month.

The referendum itself wasn't enough, though.

"For Russians, Crimea cannot be 'ours' without also being 'not theirs,'" writes Wilson.

With the annexation came a new wave of state-sponsored history, revising and minimizing the indigenous status of Crimean Tatars. Russian historian Sergei Cherniakhovskii called the annexation a "Reconquista" and denied that Crimean Tatars were a majority on the peninsula when conquered by Catherine II.

Having occupied Crimea, Russian authorities began a campaign of intimidation and harassment against Crimean Tatars, including arbitrary arrests, torture, and kidnappings.

Just as the Crimean Tatars were accused of being Nazi collaborators, now, many are imprisoned by Russia on fabricated charges of Islamic extremism.

Russian authorities have also targeted Crimean Tatar media outlets, shutting down television channels and newspapers and banning the Mejlis, the representative body of the Crimean Tatar people.

Simultaneously, Russia has followed two other key points in the Soviet playbook since annexation: demographic manipulation and distortion of history.

In addition to the many Ukrainian-identifying people who left Crimea after 2014, around 40,000 Crimean Tatars applied for the status of internally displaced persons, with the real number of those displaced likely significantly higher.

According to former Meijlis Head Mustafa Dzhemilev, between 850,000 and one million Russians moved into Crimea from Russia between 2014-2018.

Returning home

President Zelensky has repeatedly made it clear that Ukraine intends to liberate all occupied territories, including Crimea.

Nine years of Russian occupation, relentless revisionist propaganda, and the skewed demographic balance will make reintegrating Crimea one of the toughest challenges for post-war Ukraine.

Nonetheless, legally, Crimea belongs to Ukraine.

No amount of propaganda about historical lands, Soviet transfers, or the supposed "will of the people" can change the fact that forcibly annexing territory is illegal in all understandings of international law and completely unacceptable in the 21st-century world order.

But more importantly, Crimea's place as an integral part of sovereign Ukraine is a matter of historical justice for the Crimean Tatars, whose bloody and tragic experience of Russian colonialism has aligned their future path with Ukraine.

It is upon these two pillars that Crimea's status as a rightful part of Ukraine firmly stands.