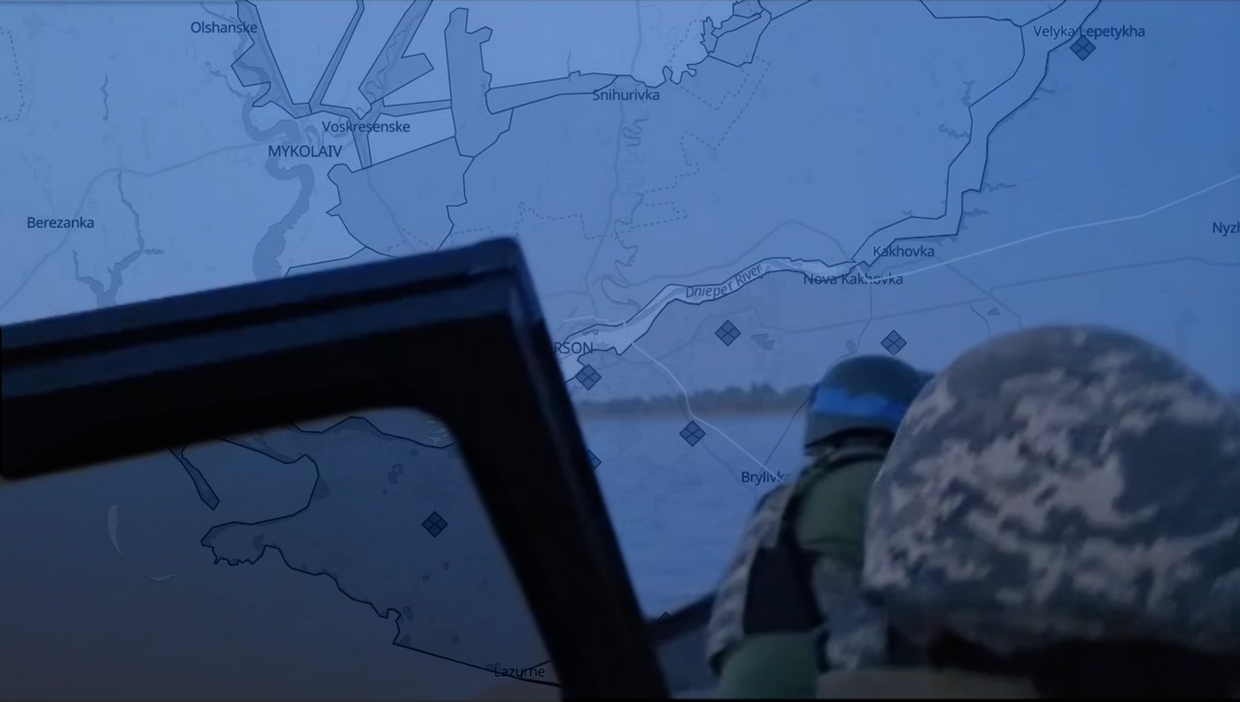

Ukrainians step up efforts to cross Dnipro, tie up Russian forces in Kherson Oblast

Pressure is mounting on Russian forces across the Dnipro River in Kherson Oblast.

Ukrainian forces have reportedly stepped up their attacks on Russian positions to try and secure a beachhead and bring heavy armor into the fight. They aren’t quite there yet, but assaults on the eastern bank could mean Ukraine is getting closer to opening a new front in the south.

Ukraine has been conducting raids into Russian-occupied territory on the eastern bank since February. Over the last few days, Russian military bloggers claimed that Ukrainian troops began bringing heavy equipment across the river for the first time.

One blogger said that Ukrainians are advancing south of the village of Krynky, located some 35 kilometers from the city of Kherson and just off the shoreline of the Russian-occupied left bank.

However, a Ukrainian special forces soldier in the area, who goes by Skif, dismissed these reports. His real name is hidden for security reasons.

“It’s not yet true about heavy equipment, but it’s true that there is more personnel there,” he said.

Experts told the Kyiv Independent that if Ukraine can put together an armored strike force on the eastern bank, it could be devastating for Russian troops, but it's unclear how they can manage with Russia's advantage in the air. Amphibious attacks are also notoriously difficult.

The raids intensified at the beginning of summer, including some confirmed raids on Kozachi Laheri in August, culminating with the latest confirmed clashes in Krynky. A few days ago, Ukraine marines were reportedly fighting “house by house,” Skif told the Kyiv Independent on Oct. 30.

“The situation changes very quickly, and it’s very difficult out there,” he said. “Krynky is not under our full control but we’re trying to move forward.”

Searching for weak points

Geolocated drone footage published on Nov. 3 by a medic from the 35th Marine Infantry Brigade showed Russian troops being gunned down by Ukrainian marines around Krynky.

This was not a frontal assault but the latest attack Ukrainian troops have carried out to tie up Russian forces and keep them from sending more reserves to the southern front. They’re likely also looking for a weak point in Russia’s defenses.

Controlling Krynky could open a safer route to Oleshky, an important Russian concentration point along the Dnipro River. But assaulting Oleshky along the main road from the destroyed Antonivsky Bridge, in plain view of Russian observation points, would be a suicide mission.

Ukraine’s raids in the northeastern direction of the river follow a pattern of trial and error, Skif said.

“We tried to breach different places, but it failed, and now we try by this flank to get into Russian defenses.”

In raids across the river on Oct. 17-18, two marine infantry brigades attacked Russian-occupied Poima, 11 kilometers east of Kherson, and Pishchanivka, 14 kilometers from the city, according to the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War.

Previously, such an attack was said to have taken place on Aug. 8, with Ukrainian forces gaining a foothold near the village of Kozachi Laheri, some 27 kilometers northeast of Kherson on the eastern bank of the Dnipro River.

Ukrainian troops haven’t managed to keep a foothold in Kozachi Laheri yet, Skif confirmed.

Russia appears to be taking the assaults seriously, as it has recently replaced its top military official in charge of operations in the occupied part of Kherson Oblast.

The move likely indicates growing pressure the Russian army faces in the area, the U.K.'s Defense Ministry said on Oct. 31, citing a report by the Russian state-run news agency TASS.

Securing a bridgehead

Russian forces have held the eastern bank since Ukraine liberated Kherson in November 2022. Since then, Russian troops have pounded the city, which sits on the western bank of the massive Dnipro River that divides the two forces.

Crossing by boat is the only option since the Antonivsky Bridge linking Kherson to the other bank was destroyed in November 2022, and Ukrainian forces don’t have enough boats to launch a massive landing, Skif said.

“If we manage to make a bridge and normal logistics, we won’t need boats,” he said. “But we need a lot of them right now.”

A secure bridgehead across the river could allow more reinforcement and keep Russian forces busy enough to reshape other frontlines, but it’s risky, military expert Serhyi Zgurets said.

The harassment keeps Russia from transferring more manpower to the southern Orikhiv-Robotyne-Tokmak front in Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

A breakthrough or the threat of one in Kherson Oblast could even force Russia to draw reserves from the occupied part of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast, bolster Ukraine’s morale, and help units fighting on the southern front by creating a diversion as the southern counteroffensive stalls.

“In the future, deeper and more powerful raids are possible in coordination with troops on the southern front deep into the territory of Zaporizhzhia,” Zgurets said.

A bridgehead would put Russian logistics at greater risk in the area, potentially complicating reinforcement from Crimea to the southern front.

Ukraine is still making progress near Robotyne, liberated in August, repelling Russian attacks day after day despite facing massive Russian fortifications and advancing on a heavily mined terrain.

Ukrainian forces also keep pursuing their offensive toward Russian-occupied Melitopol in Zaporizhzhia as part of their five-month-long counteroffensive, the General Staff wrote on Oct. 30.

Taking Melitopol, a key city between Kherson and Mariupol, would allow Ukraine to cut Russian supply lines from Crimea to Donbas and push further toward Berdiansk and the Azov Sea.

Melitopol is roughly 100 kilometers from the southern front line and has been turned into a heavily fortified area since Russian troops occupied it in February 2022.

Swampy terrain

Assaults over water are notoriously complex, especially given the marshy terrain surrounding the eastern bank of the river.

“Ukraine lacks strength for this, and it is a very risky situation,” Zgurets said.

Gaining a foothold on the other side of the river requires a sufficient number of forces and engineering equipment, in particular, pontoons, that Ukraine hasn’t deployed so far, Zgurets said.

Troops can’t bring in much-needed armored vehicles with their small rafts, which is why bringing heavy equipment across the river is a game-changer in the area.

Ukrainian assault troops mainly consist of marine units infantry equipped with small arms, crossing the river on rigid inflatables. They’re covered by artillery from the west bank of the river, Zgurets said.

It’s not enough to keep a secure position for long unless Ukraine manages to send more armored vehicles in reinforcement, ‘Skif’ said.

Naval mines litter the Dnipro bank, which makes it as tricky as the mine-strewn fields of Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

As part of its defense strategy, Russia deploys all sorts of UAVs, from FPV and Orlan 10 reconnaissance drones, to spot targets for the deadly Lancet, Russia’s homegrown kamikaze drones built at an industrial scale.

Lancet drones are likely one of the most effective unmanned weapons deployed by Russia over the past year, the U.K.’s Defense Ministry wrote on Nov. 1.

Besides drone waves and artillery, Russian forces in the area also have T-90 tanks equipped with state-of-the-art French imagers that allow the tank to fire accurately at night and in any weather conditions, Skif said. Ukrainian forces reported destroying at least two T-90 in the area in October.

Russian troops are composed of battle-hardened units and “cannon fodder” battalions, Skif said, which makes the fight even more difficult.

Russian forces coordinate professional soldiers protected by penal units called “Storm-Z,” expendable on the battlefield and sent on the first line to defend from Ukrainian assaults.

Compared to the Battle of Bakhmut or Avdiivka, Russian forces are not taking the initiative to attack but are staying on the defensive. Skif said the swampy terrain makes trenches impossible. It doesn’t make Russian forces any easier to break either.

“They have more experience now,” he said.