‘The Language of War’ searches for ways to talk meaningfully about Russian invasion

“How should I manage this anger? Or should I?” Ukrainian author Oleksandr Mykhed asks himself following the start of Russia’s all-out war.

In his book “The Language of War,” the first major Ukrainian prose work published by a Penguin imprint, Mykhed recounts how the lives of Ukrainians were upended on the night of Feb. 24, 2022. The need to find the right words to convey this anger and all other emotions stirred by the war remains pressing throughout the book. Mykhed describes how “the war now lives inside us,” underscoring how it is not just a fight for survival in a genocidal war but a profound shift in how Ukrainians interact with each other and the rest of the world.

Mykhed and his wife fled their home in Hostomel, a Kyiv suburb that was the site of heavy battles in 2022, for the west of Ukraine. But they were initially unable to convince his parents, who lived in nearby Bucha, to do so.

As a result, Mykhed’s parents lived under occupation in Bucha for almost three weeks. The name of the town has gone on to become synonymous with Russian war crimes for the terror that unfolded there, including the murder of over 450 people. For obvious reasons, the passages in the book in which Mykhed describes his parents’ ordeal in Bucha are some of the most difficult to read — one can only imagine the emotional toll it took to write them and process what his parents endured.

Mykhed also transcribes his mother’s testimony of that period and reflections on the history of her family’s history going back to World War II. The need to speak of these layers of trauma offers an opportunity to finally liberate oneself from it, otherwise, it can become all-consuming.

After she and Mykhed’s father escaped Bucha and reunited with their son in Chernivtsi, a city in western Ukraine, things that once brought her pleasure, like reading, no longer appealed to her in the immediate days that followed.

“I must surround myself with quiet,” she tells her son. “I guess this is my reaction to the sounds of explosions and everything that happened over there.”

The book includes not only Mykhed and his family’s wartime experiences but testaments from other Ukrainians who have lived through Russia’s war, including a “Cyborg,” a nickname for the Ukrainian servicemembers who fought valiantly to defend the Donetsk International Airport during heavy battles back in 2014.

Additionally, there are chapters dedicated to listing the multitude of war crimes committed by Russian soldiers on Ukrainian soil, including the burning down of the Ivankiv Museum of Local History, where 25 works by Ukrainian folk artist Maria Prymachenko were kept, as well as Russian troops’ use of phosphorous bombs in the Kyiv suburbs. The use of such weaponry is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions.

As the title of the book suggests, war changes the ways in which people communicate. The language of war is not one of culture, business, or leisure. This is underscored by how Mykhed’s parents struggle to communicate with friends who fled abroad. While they complain about issues like the state of their accommodations, his parents struggle to find the words to describe what the experience of occupation was like, ultimately finding it better not to say anything at all. War not only destroys people’s homes and lives but some of the previous ways in which they connected with one another.

Mykhed also struggles to find meaning in his work as a writer and person of culture. In Chernivtsi, he helps clear out books in library storage to set up a bomb shelter. He enlists in the Armed Forces of Ukraine and “regrets like hell” not having learned how to assemble and disassemble a gun until only a week before the start of the full-scale war.

“We will come out of this war as a changed people,” Mykhed writes. “Apart from creative writing, all my past experiences seem excessive and unnecessary.”

“The names of film directors and writers, literary methods, artistic creations now feel too convoluted and needless in the language of war. My mind prevents access to any layers of complex knowledge, focusing instead on the deeply philosophical concept of ‘shithead invaders’.”

While Russia’s full-scale war disrupts Ukrainians’ ways of life and forces them to prioritize their survival, Mykhed also contends with notions of guilt. He doesn’t suffer from survivor’s guilt, as he explains. This guilt has more to do with the fact that he “could not relate to the horror” experienced by those who fled the Russian invasion of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014 until he also lost his home.

He feels guilt for having “done so little” in the eight years leading up to Feb. 24, 2022, when so many soldiers and volunteers sacrificed their lives to keep the initial Russian invasion in the east of Ukraine contained. Additionally, he feels guilt for not having been able to convince his parents to evacuate Bucha before they were trapped under occupation, and muses about finding the right words to write a self-help book on the topic.

“Because one of the lessons I’ve learned in these couple of weeks is that the whole world must be prepared to leave everything behind,” Mykhed writes.

Mykhed also calls out those in the West who, despite supporting Ukraine, define its existence in relation to Russia: “We are something entirely different. A young, independent, dynamic nation, who knows its history and has its own vision of the future.”

For many people worldwide, Russia’s all-out war has drawn attention to the country and put Ukraine on the map for the first time. But the failure to appreciate Ukraine’s rich language, history, and culture which have persevered despite generations of Russification policies and state-sponsored violence inflicted upon the populace means that such people often fail to fully grasp what Ukrainians are fighting so fiercely to protect.

“I want to shout to the world – we are larger, more interesting, broader than the box we have been put into,” Mykhed writes. “We are greater than the war.”

A troubling result of this narrow perception is that mostly well-intentioned organizations abroad have often tried to promote dialogue between Ukrainians and so-called "good" Russians who have fled Russia. There have been numerous incidents over the past two and a half years where Ukrainian artists have publicly withdrawn their participation from major cultural events that also included Russian artists. Despite Ukrainian artists repeatedly explaining why they feel any semblance of dialogue during the war would harm the Ukrainian cause, these controversies continue to occur.

Many Western media outlets have also given a platform to Russian artists who not only bemoan the circumstances of their life in exile but take the chance to complain about what they perceive as the hostility of Ukrainians toward them. They complain about things like the dismantling of monuments to 19th-century Russian poet Alexander Pushkin across Ukraine, which, in the grander scheme of things, are insignificant.

“We share your pain,” Mykhed responds to them. “All of us, here, in a bomb shelter.”

Russia’s full-scale war is not its first act of aggression against Ukraine, not even in Mykhed’s lifetime. If Russia is not defeated in “the throes of its hungry empire,” as Mykhed reflects, then these cycles of tragedies point to a stark realization, one he calls a Ukrainian life lesson: he and his loved ones will likely have to live through this again.

“The experience I am gaining now will be essential for me then,” he writes, including a point in time where he reaches an age he “can’t even imagine.”

Mykhed’s "The Language of War" provides a sobering look into the first year of the full-scale invasion through not only his and his family’s experience but that of other Ukrainians as well. The book compels readers to confront the grim realities of war beyond the more palatable narratives of resilience and fortitude often embraced by outside observers.

The book highlights numerous examples of Ukrainians overcoming the inhumanity inflicted by Russian forces and finding strength in their shared experience, but Mykhed emphasizes the importance of never forgetting the extent of the horrors that occurred.

Mykhed’s indignation is strong and justified — such atrocities were believed to be inconceivable in the 21st century, until countries like Russia proved the world otherwise.

“This book is about things one can never forget,” he writes. “Or forgive.”

Note from the author:

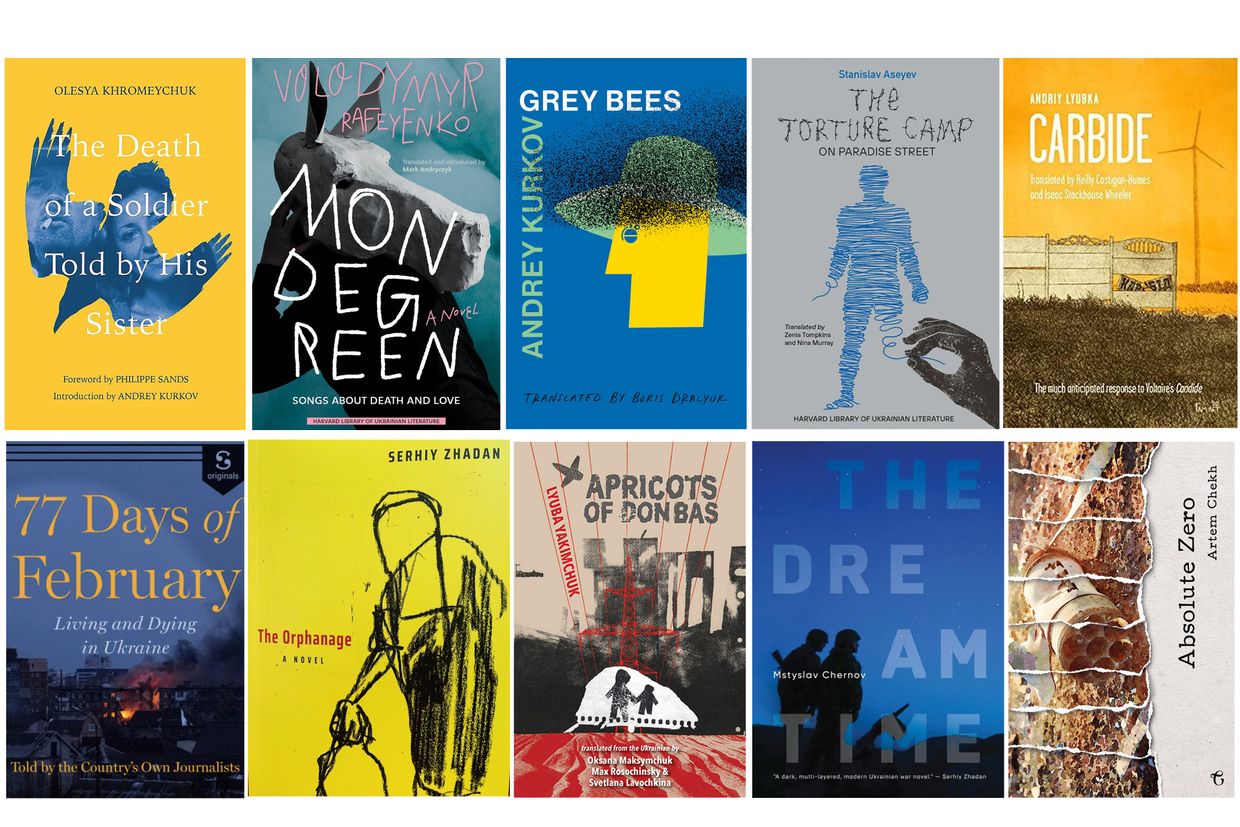

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. Ukrainian culture has taken on an even more important meaning during wartime, so if you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.